A while back, Stephen Cooke and I did one of our LENS ME YOUR EARS podcasts on spy movies, which you can find a link to here. I urge you to check it out—Stephen has an enormous knowledge of the history of movies, and I always learn something in our conversations.

But if you’re not a podcasting aficionado, here’s a breakdown of my notes spread over three blog posts. I watched more movies to prepare for that episode than any before or since, so I thought it might be fun to share those details. What follows is a bit of an overview and thoughts on Len Deighton’s Harry Palmer series. The next post is a cross-section of 40 years of spy thrillers, and the last takes a look at films adapting John Le Carré novels.

INTRODUCTION

Though there were spy movies going back to tales of Mata Hari, and certainly in the post-WWII period include classics like Hitchcock’s Notorious and Reed’s The Third Man. But it feels like this genre really came into its own in the 1960s, a two pronged response to the Cold War: James Bond and films adapting John Le Carré, like The Spy Who Came In From The Cold from 1965.

It’s also worth noting that this is a very literary genre: many of the films are adapted from novels.

Today, spy movies remain on a spectrum: 007 is still going strong, and Mission: Impossible, both on one end, and on the other the more serious geo-political dramas, examples like A Most Wanted Man or Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, both based on Le Carré books. He’s really the king of the darker, more realistic spy thriller.

What most have in common whether pot-boilers or action-packed: international locations. They often feature doomed romances. The plots are often just on this side of totally opaque, or sometimes just beyond. Lots of institutional deceit. If they work, they’re a whole lot of fun. And if they don’t, they often have incidental pleasures.

You won’t find a lot here about Bond, which is its own category altogether. But it’s interesting to note, I think, that the Mission Impossible and The Man From UNCLE TV series were both American responses to Bond, in some ways. Funny that now they’ve both found their way to the big screen, they’re pretty distinctive.

We should also mention the Jason Bourne movies, adapting the Robert Ludlum novels, four with Matt Damon as the amnesiac American spy, and one with Jeremy Renner. That franchise has changed the genre, just like the Austen Powers movies did back in the 1990s. I would argue Bourne is right in the middle of my spy spectrum: delivering the action and thrills, but they’re also with a sense of real-life. There’s also the Tom Clancy Jack Ryan series, but I recently went back to watch those, and only the first of them, The Hunt For Red October, was really any good. I found the two Harrison Ford entries pretty weak, and the Ben Affleck and Chris Pine versions aren’t a whole lot better.

The Mission: Impossible movies are a lot of fun. I rewatched the four before number five came out, and then found that Rogue Nation and Fallout were the best so far.

For my more detailed review of The Man From UNCLE, please click on the title. And for other recent espionage thrillers with a more comedic bent, here are reviews of: Kingsmen: The Secret Service, Kingsmen: The Golden Circle, and Paul Feig’s Spy. On LENS ME YOUR EARS, we’ve also done an episode on spy spoofs, such as Our Man Flint, Johnny English, and the French films, OSS:117.

HARRY PALMER

Back in the 1960s, another British spy franchise ran concurrently to Bond, the Harry Palmer movies:

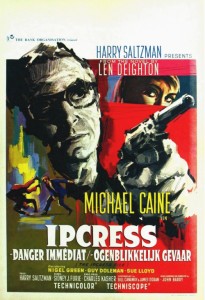

The Ipcress File (1965), directed by Sidney J. Furie from the Len Deighton novel, produced by Harry Saltzman, edited by Peter Hunt, production design by Ken Adam, score by John Barry: It’s most of the James Bond crew. Three films were made in the late 1960s, and then two more revived the franchise in the mid-1990s.

But behind the camera on The Ipcress File and Funeral In Berlin (1966) was cinematographer Otto Heller, who shot gritty kitchen sink dramas such as Peeping Tom and the Ealing comedy The Ladykillers. The style of Harry Palmer movies, with their Dutch angles and deep shadow, is nothing at all like Bond’s broad, bright sensationalism.

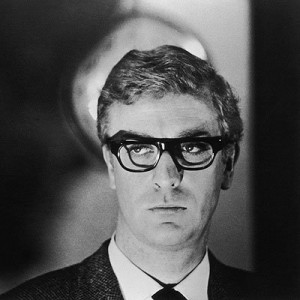

Harry Palmer wears brown-rimmed glasses. He’s very modish, a wide boy, someone who lives in a bit of a divey East End apartment. Like Bond he’s sharp, witty, and a ladies man, but unlike Bond he’s pubic school educated. He’s street smart, not book smart. Bond’s cool is born out of the ’50s, Rat Pack cool—expensive cocktails and tuxedos and Aston Martins. Palmer’s cool is out of the ’60s counterculture. Bond makes fun of the Beatles. You could imagine Palmer listening to the Beatles, driving a Vespa and drinking a cappuccino.

You could even say Michael Caine is kind of the anti- James Bond, a caustic, anti-authoritarian Cockney.

We meet Harry as he’s being shuffled between government agencies, from the military to intelligence, traded by one toffee-nosed bureaucrat to another and headed to an office at the top of the stairs across from rain-slick Trafalgar Square. There’s some indication Palmer may have committed an offence while on the job with the military, and is working off that debt. Now he has a real mission: A noted scientist has disappeared and it’s Harry’s job to try and track this fellow down, despite the inevitable paperwork.

Through his contacts at Scotland Yard he finds a local heavy who may have grabbed the VIP in question, and negotiations begin to get him back. But there’s a much more labyrinthine conspiracy afoot; this isn’t the only man missing, and when these fellows return they’re amnesiacs, unable to work. It isn’t long before Harry finds himself under the hot lights, subject to a psychedelic brainwashing experience.

This is truly a 1960s picture. It’s an immersive time capsule, with a lot of care taken with the London locations and a look and feel that I really enjoyed. The city hasn’t changed too much since then, but it’s a treat to see the crowded streets filled with 50-year-old cars.

The charm also lies in the repetitive signature in the John Barry score, the spooky lighting, and the camera set up in very weird places; I’ve never seen a film shoot so often from behind obstructions, ceiling-mounted light fixtures, or down through lampshades. If the intention of this technique is to make the audience feel off-balance, or perceive Palmer as a victim of an unseen or malevolent observer, it works. And I’ll wager I’ve never seen so much time and care devoted to the protagonist’s culinary skills as is Harry Palmer’s, but that’s no bad thing.

Funeral In Berlin adds another Bond veteran to the credits, director Guy Hamilton. It continues the anti-glamour stakes, with Palmer still railing at his boss, Colonel Ross (Guy Doleman) and joking about defecting from the get-go.

This time Palmer is sent to East Berlin to help orchestrate the defection of a Colonel Stok (Oskar Homolka), and crosses paths with a double-agent named Johnny Vulkan (Paul Hubschmid) and Israeli intelligence operative, Samantha Steel (Eva Renzi). It gets a little confusing as the action crosses back and forth across the wall, but eventually it sorts itself out, without much help from Harry—he’s not the most capable spy. The highlights have to do with style, mostly, the costumes and sets, the frequent dutch angles, and the startling lighting in the very moody nightclub scenes. We get another collection of terrific locations, including Check Point Charlie (or an excellent facsimile) and the Zoo AM Hotel.

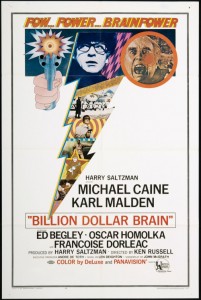

Funeral In Berlin is followed by Billion Dollar Brain (1967), directed by the notorious Ken Russell. This time Harry’s an independent, his old boss Colonel Ross recruits him back to the spygame, where he once again encounters Colonel Stok. This time he’s taking a viral weapon—contained in eggs—to Helsinki, where he meets up with an old pal, Leo (Karl Malden), and his new lady, Anya (Françoise Dorléac), and then he’s on to Russia and beyond.

A strange preponderance of nudes, illustrations, and murals are just some of the production touches, suggesting the psychedelic ’60s strain in the first picture isn’t played out, with characters taking off their clothes in scene after scene for no particular reason. Once again, Palmer isn’t really driving the action, more a hapless victim of circumstances, saying yes to offers when he should probably just say no. When he ends up in Texas, face to face with the so-called brain (a massive computer system) of General Midwinter (Ed Begley), the picture crosses over into satire.

Bullet To Beijing from 1995 and Midnight In St Petersburg, from 1996, are the two features that reunited Michael Caine with the role of Harry Palmer, though neither is based on a Len Deighton novel and both were made for television.

The first picture, Bullet To Beijing, has Caine slipping back into the role of Palmer with no noticeable wear or tear in the 25+ years since he last wore the spectacles, though I wish I could be as complementary about the script or direction or score—the gorgeous style of the original three films has been replaced with sub-Bond action sequences and the editing requirements of TV. This time there’s interest in something called the Red Death, another chemical weapon, which feels a little repetitive. Most of the second act is spent aboard a train across Siberia, which brings up unflattering comparisons with Agatha Christie, and when Palmer is thrown off, with Silver Streak. It’s also a good 40 minutes too long.

On the plus side, there’s an interesting thread about the empty lives of unemployed intelligence operatives following the cold war, and a cast that includes Michael Gambon, Michael Sarrazin, Mia Sara, and Burt Kwouk, veteran of actual 007 films (yes, plural) and the Pink Panther series. Jason Connery is also on board, but he seems absent much of his father’s on-screen charm.

One of the best moments arrives late in the running, after a gun battle, when Sarrazin, suavely and gingerly, steps out of a car and shakes the spent cartridges out of his jacket. Never seen that move before.

Midnight In St Petersburg was shot back-to-back with Bullet, and continues Palmer’s story of setting up a security business in Russia, as if such a thing was even possible for Brit, let alone one who made his living in the intelligence services. His company is (cunningly) called Fitz-All T-Shirts, The plot here has something to do with missing plutonium and troubled ballerinas. but the film was so painfully ham-handed I may have blocked out more plot detail.

In the following post are reviews of a dozen spy thrillers from 1966 to 2006, and in the third you’ll find reviews of a number of films adapting John Le Carré novels.