40 YEARS OF SPY THRILLERS

In the first post I watched the Harry Palmer movies, and the third I look at the film adaptations of John Le Carré novels. Here’s a cross-section of stellar—and not-so stellar—spy movies through the years.

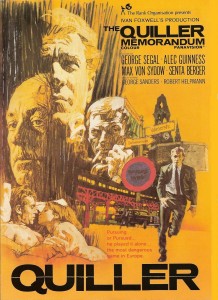

The Quiller Memorandum (1966) was directed by Michael Anderson, Harold Pinter wrote the screenplay based on a novel by Trevor Dudley Smith.

George Segal is Quiller, an American spy the way Elliot Gould was a private detective in The Long Goodbye. Kind of fumbling, charming but not demonstrating a lot of skill in his work, necessarily. He’s in West Berlin, replacing a guy who got killed, who replaced a guy who got killed. They were all looking a neo-Nazi group, led by Max von Sydow.

Quiller wanders around looking for the Nazis and meets a young German teacher named Inge (played Sente Berger) who gives him a lead. Alec Guiness (who would go on to be a famous TV spy in the British productions Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People) is his controller, who mid-movie offers a deft clarification of the plot using two muffins and a raisin.

The Quiller Memorandum has a great wide-angle look (there’s a couple of terrific overhead shots where the camera pulls back to reveal we’re looking through a window, ingenious work I’ve never seen before) and a very lazy way around its narrative. I really enjoyed it, but it’s a standout in its genre for not really giving a damn about thrills.

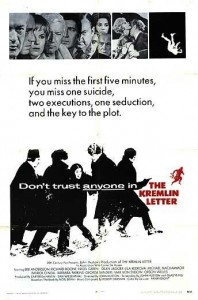

The Kremlin Letter (1970), directed by John Huston, who wrote the screenplay from the Noel Behn novel.

Patrick O’Neal is a Navy Intelligence officer named Rone who gets press-ganged by the CIA to work on a sting in Moscow. Shot in Rome and Helsinki, it’s really well cast, including Huston in a single scene, Orson Welles and Max von Sydow as Russian military men, George Sanders as a spy named Warlock, and Bibi Andersson as the pawn of many diabolical men.

It’s dated, but in some ways it is the prototypical spy movie: Cold War, solid locations, an overly complicated plot, betrayals and reversals, and a little glamour in Rone’s particular gifts, but mostly a dark, morally ambiguous drama.

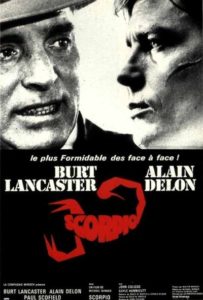

Scorpio aka The Scorpio File (1973), directed by Michael Winner, written by David W. Rintels and Gerald Wilson

The first thing you’ll notice about this one is, aside from the excellent Paris location work to open matters, is a heavy-handed score. But otherwise Winner’s energy with the camera — lots of shots tilted up at the ceiling, lots of dramatic close-ups — keeps you engaged.

As an action star, Burt Lancaster is a little long in the tooth at 60, and his suit and hat feel like they’re 15 years out of style, but that’s part of the story. He’s a veteran spy named Cross who mentored a deadly young-ish turk, a freelancer named Scorpio (Alain Delon), to replace him.

Scorpio was assigned to kill Cross in Paris by CIA bigwig MacLeod (Canadian actor John Colicos), but for some reason he didn’t. Is it loyalty or something else? He has a girlfriend (Gayle Hunnicutt) in Washington DC, and there’s another loose end, a Russian academic and spy in Vienna, Zharkov (Paul Schofield), an old friend of Cross’s. The best bits of the movie, aside from some pretty fun action sequences, are when Cross and Zharkov get drunk and bitterly reminisce about what they’ve done with their lives.

Wildly successful genre producer Walter Mirisch was the money behind this one, and Winner directed two Charlie Bronson pictures before it, including the hitman mentor picture The Mechanic, and two after. It’s slick, stylish, and more than a little entertaining, but certainly as much a thriller as a spy movie, but the plotting is jagged and the international locations well shot. Winner can’t resist evoking a bit of The Third Man in his Vienna scenes.

A few things made me shake my head: Lancaster wears blackface in disguise, and Delon isn’t nearly as convincing an actor in English as he is in French. Weirdly, his character has a thing for cats — probably speaks to his character’s “independence.”

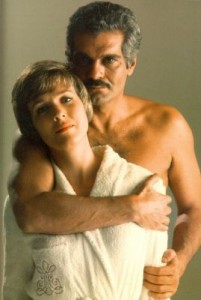

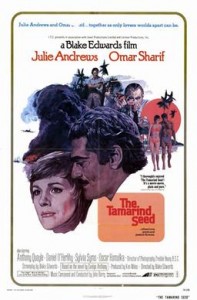

The Tamarind Seed (1974), directed by Blake Edwards, and starring Julie Andrews and Omar Sharif, written by Edwards from an Evelyn Anthony novel.

Blake Edwards is mostly known for his comedy work, movies like The Pink Panther, but he takes a very different approach here. The Tamarind Seed doesn’t have a great reputation, so I was surprised how much I enjoyed it. Interesting it also has a 007 connection: opening credits from Maurice Binder and a terrific, angular John Barry score.

Andrews plays a heartbroken British woman who works for an important man at the British Home Office. She’s just ended an affair with a married diplomat and has flown off to Barbados to recover. There she meets Sharif’s Russian spy. The Egyptian actor is maybe the least convincing Russian I’ve ever seen on screen, but what he misses in Balkan grit he makes up for in smooth sensuality. He determinedly woos her, even back to London, despite his being posted to Paris.

The fact of their liaison is trouble for both of them. She’s warned by British intelligence to steer clear of him, while he tries to convince his people he’s turning her.

The real fun of it is trying to figure out if he is being sincere or not. He’s remarkably frank about his being a professional liar, but that’s what makes it his character so compelling. If she believes everything he says she can’t very well trust him. All this against the backdrop of the bed-hopping diplomatic corps in Paris, and how the intelligence service manages all of the infidelity.

It’s quite a philosophical story while it fulfills the spy genre requirements of reversals, betrayals, thrills, and great locations. The action, when it finally arrives, is extraordinarily badly shot, but I really enjoyed everything that led up to it. Here’s a movie desperate to be rediscovered and maybe even remade, updated for the new millennia.

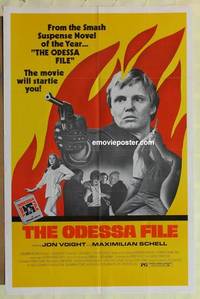

The Odessa File (1974), directed by Ronald Neame, from the Frederick Forsyth novel. Forsyth also wrote Day Of The Jackal, Dogs of War and The Fourth Protocol, novels adapted to compelling British war, mercenary, and spy thrillers, respectively.

In this one Jon Voight plays a Hamburg-based German journalist, Peter Miller. He stumbles upon the diary of a recent suicide, a concentration camp survivor. Miller goes undercover to find the SS officer who ran the camp.

Voight’s accent isn’t bad, but it’s one of those pictures where English and American actors put on German accents and act opposite German actors speaking English, and it’s all very weird. Occasionally we get to hear actual German in subway announcements.

Overall it’s a passable genre entry, with some decent location cinematography, but not hugely memorable. I thought Day Of The Jackal, about an attempt to assassinate De Gaulle, and The Fourth Protocol, a mid-80s Michael Caine thriller about the effort to smuggle a nuclear weapon into the UK, with a young Pierce Brosnan as the bad guy, both had more suspense. This is more of a procedural and a mystery.

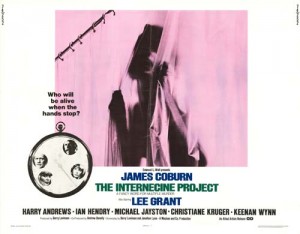

The Internecene Project (1974), written by Mort Elkind, Barry Levinson, and Jonathan Lynn, directed by Ken Hughes and produced by Levinson.

In her autobiography, Lee Grant barely mentions this entry in her filmography. I think she calls it “flimsy,” a movie with a 16-page screenplay when they started shooting. She wanted to work with James Coburn, so she agreed to it.

Coburn is a former spy who’s getting a sweet government position, but wants to cover up his past, so he orchestrates a satisfyingly twisty operation whereby four of his former associates murder each other on the same night. It capitalizes on being London-set, though it’s mostly interiors in dark, over-furnished rooms and poor back-projection—entertaining but trashy. The copy I saw had a lot of grain in it. For real thriller fans out there, look out for a terrifically creepy shower strangulation scene (as per the poster above).

Fans of Coburn would do well to program this opposite The Last of Sheila, another movie where he arranges a complicated and murderous puzzle with former colleagues, except it’s set on a yacht.

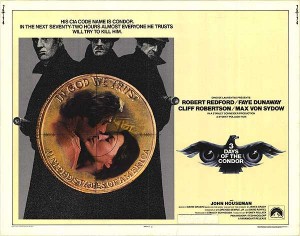

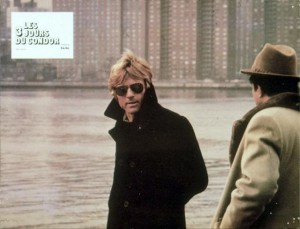

Three Days of the Condor (1975), directed by Sydney Pollack, with a screenplay by Lorenzo Semple Jr, and David Rayfiel. Based on the James Grady novel Six Days of the Condor.

A high point in American spy thrillers, Robert Redford is Joe Turner, a CIA analyst (“I just read books!”) who works in a quiet office in Manhattan with a group of other bookish people. One day, while Joe is out getting lunch, Max von Sydow (him again) and his thugs show up and kill everyone. Joe is on the run, trusting no one, even his superiors, most of whom he hasn’t met. It’s a gorgeous looking film, very autumnal, with plotting and suspense as tight as a drum.

I wasn’t entirely convinced of the potential romantic connection between Redford and his erstwhile captive in Brooklyn, Faye Dunaway, or that she would basically suffer from Stockholm Syndrome and do everything he asks, but this is otherwise a thriller that genuinely thrills. Love the World Trade Centre location work.

It would make a great New York double-bill with:

Marathon Man (1976), directed by John Schlesinger, written by William Goldman, from his novel.

I love how this movie starts: An old Nazi getting into a road rage incident that concludes with his death. Dustin Hoffman and Roy Scheider play unlikely brothers—they look nothing like each other. Hoffman, the grad student who runs for exercise, kind of a novel thing in movies at the time, begins a romance with exchange student Marthe Keller. Scheider has a mysterious job.

Meanwhile, a terrifying Nazi Dentist, Szell, played by Lawrence Olivier, wants diamonds. He’s extraordinarily paranoid, and needs to know whether it’s safe to pick up said diamonds in New York. Somehow he gets the idea Hoffman knows, leading to maybe the most famous torture scene in Hollywood history before, I dunno, Pulp Fiction? This is a drama that solidly crosses over into emotional horror, and accordingly has a very special place in the annals of spy thrillers.

The Osterman Weekend (1983), director Sam Peckinpah’s last movie, adapting a Robert Ludlum novel.

Ludlum, who is probably best known for having written the Jason Bourne books, doesn’t shine here, and neither does Peckinpah, who was well past his best when he made this film. This is despite the astonishing cast, including Rutger Hauer, Burt Lancaster, and John Hurt. It’s one of those times when the over-convoluted plot did the drama no favours. It has interesting things to say about the ubiquity of media and surveillance, but doesn’t say them in a memorable way.

No Way Out (1987), directed by Roger Donaldson, based on The Big Clock, a novel by Kenneth Fearing. It was made into a very different movie in 1947.

Kevin Costner stars, back when he was young, svelte, and dangerous. He’s great, and though this is a wildly implausible thriller, somehow it all works. Costner is Tom Farrell, who gets a job working for Gene Hackman’s David Price, a married senator with a secret girlfriend (Sean Young, when she was also dangerous. She reminds me a little of Greta Gerwig).

Turns out Costner’s character is also sleeping with her. This was my favourite part of the story, the set-up where two men are with the same woman, and we get a lot of 80s synth on top of a syrupy score. Costner winds up stuck in the Pentagon while everyone’s looking for him. There’s an outrageous final twist which maybe isn’t earned, but overall it’s super-suspenseful and cleverly constructed.

A Quiet American (2002), directed by Phillip Noyce, written by Christopher Hampton and Robert Shenkken from the Graham Greene novel.

There’s a 1958 version written and directed by Joseph L. Mankewicz, which I gather Greene didn’t like because the filmmakers turned the anti-American slant of the novel to anti-Communist. Well, the 2002 version reverts to the original intent, which Greene didn’t live to see, but would likely have enjoyed far more.

Michael Caine as the cynical British reporter in Vietnam, in love with a local woman, Do Thi Hai Yen, while a younger American medical worker, Brendan Fraser, befriends Caine’s character and falls in love with his girlfriend.

I liked the movie, but didn’t love it. The love triangle (baldly analogous to the relationship Britain and the US had with Vietnam) is much more successful than the political drama, which is transparent. Fraser’s character obviously is on some secret mission in Vietnam, and there isn’t much suspense around any of his motivations. But the performances and the sense of place are strong.

Syriana (2005), written and directed by Stephen Gaghan, based on See No Evil, a novel by Robert Baer.

Multiple, parallel and intersecting storylines about people managing the social, political, and geopolitical bedrock of the oil industry in the Middle East. It’s dry, yet terrifying in places, with great roles for Matt Damon and Jeffrey Wright. What makes it a spy movie is the section with George Clooney as the disaffected spy Bob Barnes. As a post-9/11 thriller it’s powerfully astute, and difficult to shake off.

Munich (2005), directed by Steven Spielberg, written by Tony Kushner and Eric Roth, based on the book by George Jonas.

Munich recreates the events at the ’72 Olympics in Munich, where Israeli athletes were killed by Islamic fundamentalists, framing it as the moment where the world really took notice of the Israel/Palestine conflict. Afterward Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir pulled the trigger on a black ops group of agents sent to kill anyone directly funding or associated with the terrorists, all unofficially sanctioned and supported by the government.

Managed by Gefforey Rush but led by family man Eric Bana, with Ciarán Hinds, Daniel Craig, Matthieu Kassovitz, and Hans Zischler, this is one of the best casts Spielberg ever assembled, also including Michael Lonsdale, Matheiu Amalric, Ayelet Zurer, and Canadian Marie-Josée Croze.

The film works as a chilly spy thriller but also as an examination of the costs of violence on those tasked to do that work, and the broader human costs on society. It even works as an investigation into the parallel of sex and death. I think it’s as good as any of Spielberg’s films from Shindler’s List to Raiders Of The Lost Ark. I’ve had conversations about this film through the years—one hawkish supporter of Israel was appalled at this film, the suggestion that Mossad agents would have any compunctions killing Palestinian terrorists and the men who funded them. I disagreed: the film does a rare thing in imagining the human cost of that kind of work, and the film impresses with every rewatch.

One more nod I feel compelled to include, but it’s to a series of TV movies: David Hare’s Worricker Trilogy: Page Eight, Turks & Caicos, and Salting the Battlefield, starring Bill Nighy, Rachel Weisz, Christopher Walken, Winona Ryder, and Helena Bonham Carter. If you’re at all interested in this genre, seek them out. For my full reviews, go here.