With The Matrix: Resurrections now in cinemas, it seemed an appropriate time to go back to the original films. My 2021 reviews of those movies are below:

The Matrix (1999) | Written and Directed by Lana Wachowski & Lilly Wachowski | 136 min | Crave and VOD

This is the movie that launched a million memes, internet rabbit holes, and even a full-on documentary about the nature of reality. The most wildly influential science-fiction movie since Blade Runner, it’s still a marvel of construction and impressively satisfying as an action thriller.

The other day on CBC Radio I spoke to Rad Simonpillai about its pervasive reach in the culture — how college courses were built around its philosophy, how its use of CGI — and that iconic bullet-time shot — changed the way movies are made, how it interfaces both with pre-millennial tech fascination and Y2K anxiety, and how it’s now considered a trans narrative.

(My chat with Rad didn’t make it online, but his conversation with a CBC host in the Yukon did if you want to give it a listen.)

It also changed the sunglasses industry.

The opening is a tour de force. Rather than introduce us to the messiah-like protagonist, it starts with disembodied voices, and cops attempting to arrest a black latex-clad woman, Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), in a darkened room. She kills the cops but runs from agents (in suits and sunglasses) across rooftops. They’re led by Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving wielding fantasy cinema’s best enunciation next to Alan Rickman’s Snape).

Remember, in 1999 the real era of the superhero movie was still ahead of us: X-Men wouldn’t arrive until the next year, and watching someone plausibly run up a wall or jump 25 metres from building to building was still a genuine novelty, but that’s what Trinity does — followed immediately by one of those nasty agents.

All this sets up the initial concept of a secret war between a shadowy FBI-like cabal and a super-powered rogue force. It’s funny how that’s kind of a red herring, but it hooks us — especially when Trinity vanishes inside a phone booth (how quaint) just as it’s crushed by a truck. Then we go down into the phone receiver — because you needed a landline back then to access the internet!

When we finally meet our hero, Thomas Anderson aka Neo (Keanu Reeves), he’s asleep and about to wake up. Neo doesn’t have to do anything to be this special individual, to be a saviour, he simply is. Wouldn’t it be great if life was like this?

It’s not long before Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), the mysterious hacker terrorist prophet, shows him the truth: the world as we know it is a simulation, the Matrix, created by a race of AI machines to keep us in a dream world while our bodies serve as a bio-electric power source. What they’re doing beyond monitoring our battery life and stamping out human resistance isn’t really explored. Did no one think to ask? Neo may be the Second Coming, the key to freeing the human race from the computer overlords.

What’s also convenient is when Neo gets free of the Matrix, he still is able to learn via computer input directly into his brain. He becomes a martial arts master thanks to 10 hours of direct downloads.

The movie spends most of the first act teaching us the rules of The Matrix. It’s a lot of exposition, but it’s also a lot of fun. Watching it now makes me realize how indebted Inception is to what the Wachowskis do here.

What makes Reeves perfect for this material is he’s something a blank slate — you can project whatever you want onto him. At this point in his career he really struggled to show much of an interior life — he’s a lot better actor more than 20 years later — but it really worked in 1999 when you need a Christ figure in the middle of your movie. Moss is solid as a counterpart to Neo, but she’s almost too much like him, physically, like Tom Cruise and Demi Moore in A Few Good Men — they have a sibling dynamic rather than any genuine romantic heat.

The film delivers a giddy energy to the action sequences, and an ironic twist: Everything we see that happens in the Matrix is a lot more fun than what happens in “the real world,” both literally and figuratively. The movie really comes alive when we’re actually in the simulation, and that’s where Yuen Wo-Ping, the masterful action choreographer, gets to do his thing.

Another argument I’ve heard is The Matrix is really just a movie about movies. Or it might be about the appeal of fantasy without making a compelling case for its alternative. When the human team are betrayed by one of their own, it does make it hard to blame him for wanting that steak dinner.

The drama is never as engaging when we’re on the human team’s ship, and watching it again years later it still seems weird when the characters talk about Zion — it’s the hidden, human underground city that the machines want to destroy. It certainly feels like an opportunity for a better understanding, but we never get to see it in this first film.

The Matrix tries to make it OK to enjoy the fetishization of all the gunplay, the shells dropping in slo-mo like rain, and Neo and Trinity murdering all those police officers and guards. We know in the Matrix it’s all an illusion, so what does it matter? Just enjoy it like a theme park or a First Person Shooter! Not as easy to do these days.

The Matrix Reloaded (2003) | Written and Directed by Lana Wachowski & Lilly Wachowski | 138 min | Netflix and VOD

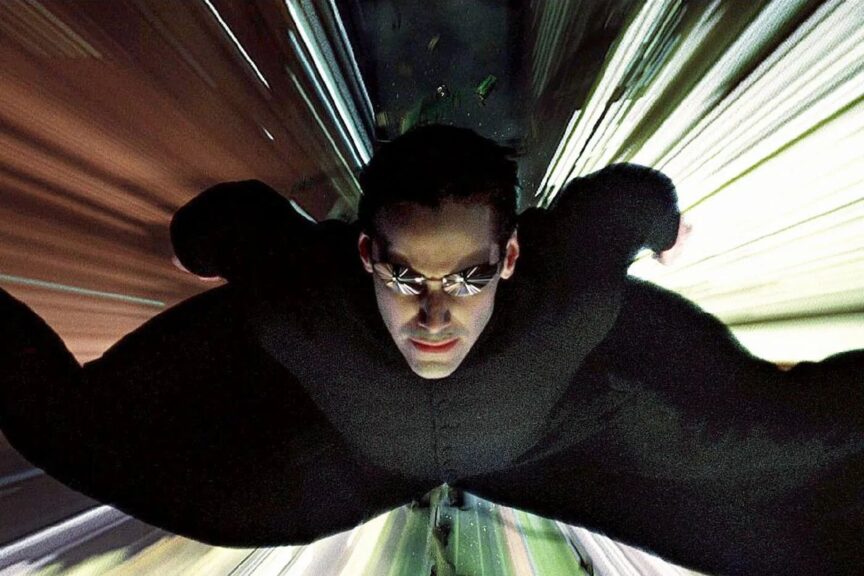

“I’m going to show these people what you don’t want them to see.” That’s part of Neo’s monologue at the end of The Matrix before he takes to the skies, a new superhero in the Matrix world.

I was so psyched to see this sequel because I’d weirdly preconceived what its plot would be: Where the original has focused in on the core conspiracy — the small band of rebels raging against the machine — I expected the second movie would go much wider. We’d see the impact of this super-powered messianic figure, see him use his power to try and convince the masses that they are slaves, broaden the scope of the thing. How would Neo be received by the people? How many people would take the red pill, given the chance? How many could they unhook from the machines and bring into the real world? The socio-political possibilities of this concept really excited me.

But, instead, the Wachowskis doubled-down on a much more traditional war movie narrative. Worse, we have Neo reverting to an earlier version of his character. At the end of the first film he’d found his mission, he knew who he was and what he was capable of. At the start of the sequel, he doesn’t know what to do with that. It stunts his character arc.

He can still kick ass, though, even in his new black monk robes, but so what? The opening action sequences seem like window dressing to a story without much direction. The tension here is between Morpheus, who believes Neo is “The One,” and the other humans who don’t believe in prophesies, only in the imminent machine apocalypse. The Matrix felt both prescient and present. The sequel feels like a World War II movie, with added hippie set dressing and more Star Wars references.

Yes, we do finally get to see Zion — it’s grimly Victorian, even Brazil-ian in its steampunk mechanics. I guess a certain analogue approach would make sense given the computerized enemy, but the time spent in Zion is just dull. That is until we get to that orgy/rave.

There’s nothing in the second film more controversial than that scene, which in retrospect, intercut with Trinity and Neo having sex, looks a little too much like a fragrance ad. The problem at the time was that raves were thought to be so 1990s. With a single movie the zeitgeist had left the Wachowskis behind.

But it’s also one of the moments in this franchise where the Wachowskis swing for the fences. It’s something they do in every one of their films, but it means just as often as they’ve succeeded, they frequently fall on their faces. If you’ve seen Jupiter Ascending or Speed Racer you might not disagree with me. And I’m one of the few who genuinely enjoyed Cloud Atlas.

Then we get another meeting with The Oracle (the late Gloria Foster, in her final role) bringing more gobbledygook, more plot driving character rather than the other way around.

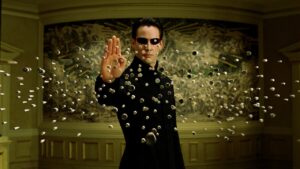

That’s followed by the most excellent scene of Neo fighting an army of Agent Smiths, who are upset at having had their purpose revoked.

That’s ironic when you consider how the film itself struggles to recover from its protagonist being so uncertain about his own purpose. All of this seemed settled at the end of the first feature, but by taking away Neo’s confidence, the picture itself feels unfocussed. The deepest observation seems to be, “Some things change, and some things stay the same.” Sheesh.

This sequel also makes the mistake of spending waaay too much time out of the Matrix. Dirty human rebels fighting squidio-machines is nowhere near as fun as Neo fighting armies of agents and exploring the limits of his abilities. But we do finally get there, triggered by the arrival of Monica Bellucci in a lovely dress.

A central action sequence — starting in an arsenal of antique weapons and ending in a freeway truck/motorcycle/sedan mash up — helps forgive all manner of cheap philosophizing, dull musing on life’s purpose, and cheesy declarations of devotion between Neo and Trinity. It’s amazing, and probably the best set piece in the trilogy.

The film ends with Neo exercising his superpowers in the real world, and the credits roll after a cliffhanger that puts a stop to any of the possibly accumulated goodwill.

The Matrix: Revolutions (2003) | Written and Directed by Lana Wachowski & Lilly Wachowski | 129 min | Netflix and VOD

When we start this one Neo’s stuck in a pristine subway station — a virtual liminal space, waiting for a train. It’s as good as any analogy for the way we’re starting to feel as an audience. The filmmakers are once again moving pieces around a chessboard for no apparent reason — the plot stuck in neutral as antagonists rise and fall and we’re left spinning in place.

Somewhere off in the distance the machines are drilling into the earth toward Zion while Morpheus, Trinity, and the Seraph (Collin Chou) go back to the Matrix, back to the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson) and Persephone (Bellucci) to try and locate Neo stuck at the subway station, which they do. That leads him back to the Oracle (now Mary Alice)… for the third time. “Where is this going? Where does it end?” asks Neo. It’s an entirely reasonable question — I’d been wondering that myself.

It turns out elements of the Matrix are invading the real world, not just the machines — who finally arrive in Zion, leading to supporting cast characters we don’t much care about wearing mech battle suits and carrying bazookas, fighting off the squidio machines until they’re overwhelmed or trigger an EMP to stop them… for awhile. This while Agent Smith, totally rogue and reproducing like a virus in the Matrix, seeks to destroy Neo.

In theory this all should be pretty cool, but it’s actually totally exhausting. I haven’t even mentioned that the humans travel around in space ships through a vast network of underground tunnels within in the earth, have I?

In the end these movies are an argument between pragmatism and faith, and the way they purport to offer belief as a reasonable substitute for empirical data or even logic feels downright irresponsible. But I won’t deny it makes for a compelling fantasy movie.

Yes, I mean that in the singular — despite a few fun moments the two sequels are simply inessential. Full credit to Ben Travis at Empire Magazine for untangling the plot threads of Reloaded and Revolutions. I just watched the two movies, and his recap made a lot more sense than the movies did.

We’ll see about that third one.