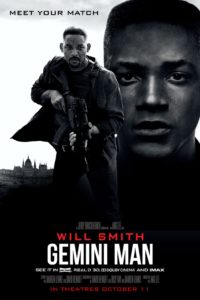

Directed by Ang Lee | Written by David Benioff, Billy Ray, and Darren Lemke | 117 min | Netflix

For a chunk of its running time, I was confident Ang Lee’s action thriller was gonna be the quintessential three star picture—if I was still giving reviews with star ratings—a perfectly fine action picture from a filmmaker who never met a genre pool he didn’t want to dive into. But whatever generosity I’d mustered soured in the homestretch. This is a movie with problems it never quite solves.

The film arrives on screens freighted with Hollywood lore, starting with a script attached to many A-listers from Mel Gibson to Harrison Ford from the late ’90s onward. A recent article in the Hollywood Reporter explained how Lemke, the original writer, gets credit on the film even though with the years of rewrites whatever remains of his original work has become unrecognizable.

Gemini Man is apparently available to be seen in super-hi-def, 120 frames-per-second, though not in Halifax. Here’s it’s available in IMAX and 3D. I chose to not see it in 3D, and while the visual definition in my screening looked digital and sharp, it wasn’t incredibly out of the ordinary. If anything, the visuals present as an austerity of style.

Lee has stepped up, like James Cameron, as someone fascinated with the bleeding edge of digital technology, so on the surface would seem like a good choice for this material: a thriller about a stone cold assassin beset by a younger version of himself. Turns out the picture has two major problems: the CGI version of 22-year-old Will Smith is an Uncanny Valley horror, and the 22-year-old script isn’t very good.

The script issues didn’t occur to me right away. As I said, I was digging those ’90s-era slick action hero tropes, as cliched as they are—the wildly talented government killer, Henry Brogan (51-year-old Will Smith), who can hit a target through the window of a speeding bullet train, decides after a long, bloody career, to call it a day and retire to Georgia. His retirement lasts for about 24 hours, when an old buddy tells him his last job may have been a set-up, and he easily spots the lady on the fishing dock, Danny (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), as someone paid by his employer to keep an eye on him. Before long they’re on the run from an agent with a familiar set of skills, Brogan’s younger, cloned self, cultivated in a lab by another of Brogan’s old buddies, Verris (Clive Owen).

All the of this is fine—even the weightless CGI action sequences aren’t too egregious, though they pale when considered against similar work in Mission: Impossible movies, partly because those pictures convince us that 50-something Tom Cruise is actually risking his life. But here, the thrills are strangely distant and emotionless—this from Lee, a filmmaker whose talent for humanism has distinguished his work, from Sense And Sensibility to Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, from Brokeback Mountain to Life Of Pi.

When Brogan’s youthful doppelgänger appears, Brogan’s reaction is not to use his skill and experience to end this monstrosity of science, but save him. Brogan’s theory is that his younger self would have the same doubts and fears he had—despite Verris assuring us otherwise—and they shouldn’t have to kill him to stop him. Seems like an especially bad idea, especially when the younger man, called Junior here, was created without Brogan’s knowledge or permission. Is he even a human being? The rich implications of a younger double are set up and then left there, largely unexplored.

The picture doesn’t generate much compassion for Junior, and then the CGI fails to convince. At best he’s a wax doll, at worst a “ghost with a gun,” one of the script’s worst lines that serves to describe a terrible visual effect. This isn’t the wondrous and impressive de-aging of Guardians Of The Galaxy Vol. 2, this is much closer to the substandard work on Carrie Fisher in Star Wars: Rogue One. It doesn’t help that we all know what Smith looked like back then, and are constantly comparing what the film shows us with our memories of the French Prince.

Junior’s existential weirdness might be enough to distract you from the clunkers in the script, which become more frequent in the last act. Plot holes big enough to hide a squad of assassins is one thing, but the awful dialogue and a wooden performance or two—I’m looking at you, Owen—drag the whole production down to where an atmospheric score, some welcome, familiar faces, like Benedict Wong and Ralph Brown, and an easy chemistry between Smith the elder and Winstead, just can’t save it.