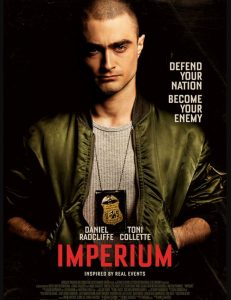

Imperium

Directed by Daniel Ragussis | Written by Ragussis and Michael German | 109 min | On iTunes and Blu-Ray

Nate Foster (Daniel Radcliffe) is an FBI agent—young, bright, and bushy-tailed—who goes from nerdy analyst to hardcore undercover agent working under tough-as-nails supervisor Angela (Toni Collette). His job is to infiltrate a radical cell of the white power movement and track down an influential conservative radio host (Tracy Letts) who might know the whereabouts of stolen radioactive materials being brought into suburban and rural Virginia.

Radcliffe is perfectly cast as Foster. His character seems initially a poor choice for the kind of steel that an undercover agent requires, but his ambition surfaces and, despite his inexperience, his smarts pay off. Also stellar are Chris Sullivan and Sam Trammell, offering two very different faces to the organized, racist rhetoric.

Imperium is the model of a taut, wet-palm inducing suspense thriller. Ragussis knows how to the sustain the tension, using a lot of terrifying stock imagery of supremacist propaganda to build the stakes. Purporting to be based on actual events, what it says about terrorist organizations operating in the United States is chilling. Given the racism that’s bubbling up around the American election, the relevance of this material feels especially appropriate and timely.

If the conclusion is just a little anticlimactic—some of the factions Foster rubs shoulders with vanish from the story and don’t return—the nerve jangling will carry through and beyond the final credit roll, maybe because we all know those fascists are still very much out there in the world.

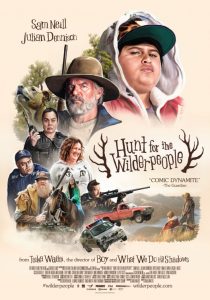

Hunt For The Wilderpeople

Directed by Taika Waititi | Written by Waititi, adapting the book Wild Pork and Watercress by Barry Crump | 101 min | on iTunes

A wonderful family movie from New Zealand, directed by the What We Do In The Shadows filmmaker whose next film is a Thor sequel. I hope he’s given free rein with the Marvel movie, because the evidence here is he’s got a great touch. This is the kind of story that looks simple to execute, but so many pieces have to work exactly right to maintain this kind of faultless management of tone.

Ricky Baker (Julian Dennison) is a troubled kid who’s been kicked out of multiple foster homes before landing in the hillside shack belonging to Bella (Rima Te Wiata) and Hector (Sam Neill). Initially resistant, Ricky warms up to the couple, but following a tragedy, Ricky and Hector take off into the bush, hunted by the cops and the lady from social services, Paula (a fierce Rachel House).

The gags come thick and fast, with street-savvy Ricky naming his dog Tupac and reminding his curmudgeonly “uncle” Hec that running from the cops through the woods is just like Lord Of The Rings. Beyond that there’s room for moments of pathos, touching on themes of loyalty, even in a makeshift family. It’s a beautifully shot film, with Waititi maximizing the landscape with the frequent use of a drone camera. It’s imaginatively scored, a mix of well-chosen retro tracks and ’80s synths, and one dazzling panorama shot backed by Leonard Cohen’s “The Partisan” that manages to reach beyond a light boys-own adventure to something truly cinematic, a little like Wes Anderson without the tightly framed whimsy. For that shot alone, Hunt For The Wilderpeople would be remarkable, but including the rest of it, it’s fantastic.

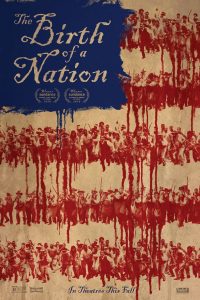

The Birth Of A Nation (2016)

Directed by Nate Parker | Written by Parker and Jean McGianni Celestin | 120 min | Available for pre-order on iTunes

It’s rare to see a film that opens weighted with such controversy about both its content and its creators.

In January, this indie film was feted at Sundance, and purchased for a record-breaking sum ($17.5 million) by Fox Searchlight. All reports suggested the film was an antidote to the #OscarsSoWhite trend of award-winning films with no nominations for people of colour. This is a true-story-inspired tale of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave revolt in Virginia. The writer/producer/director/star, Nate Parker, who’d done good work as a performer—Red Tails, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, and Red Hook Summer—was poised to become a new auteur star in the Hollywood pantheon, and the press was on his side.

Then news of Parker’s past broke: He and his co-writer, Celestin, were charged with sexual assault when they were back in college in 1999. Parker was acquitted, and Celestin’s conviction overturned in appeal. The accuser in the case eventually committed suicide.

Since these revelations came out in August, the controversy has dogged the film and the filmmakers in the press. This kind of attention has done damage to other filmmakers’ reputations, but they’ve continued to make films in and out of Hollywood.

It’s a complicated issue. As part of the audience for what Hollywood chooses to put in cinemas, many argue we have a right, maybe even a duty, to boycott certain product. It’s our one way to show that we aren’t prepared to put money in the pockets of men—and, let’s face it, it’s almost always men—who abuse women. But then, these are details of something that happened almost 20 years ago, where the men in question were never convicted of a crime.

Parker hasn’t helped his case by appearing recalcitrant and not offering much in the way of remorse, beyond some quotes on what he’s learned about consent in the years since college . It’s prompted a lot of conversation, even responses from some of the film’s cast. There’s also the question of whether Parker is being unfairly targeted because of the colour of his skin in this time of heated discussion around race in the United States. His film, after all, is about historic insurrection, about black lives mattering. And then there’s the question of whether the film takes too many liberties with history.

My approach has always been to do my best to separate the art from artist. The alternative is to stop watching a lot of feature films, and stop listening to even more music. This is why I try to steer clear of the tabloid hunger around the personal lives of filmmakers, actors, and musicians: It sours attempts at objective assessment and appreciation of the work, which is always my intent. But I totally understand and empathize with those who decide, in this case, to boycott.

So, with all of this on the table, here are my thoughts on the film:

The Birth of a Nation, appropriating its title from the 1915 DW Griffiths racist epic, is clearly a passion project, and its pace and energy reflects that fervour. Parker has gone on record as saying he was inspired by Braveheart, another violent drama about a historic revolt where its hero is martyred for his cause, with its filmmaker doing double-duty as its star. I was no fan of Braveheart—it felt too much like Mel Gibson self-mythologizing and working out some personal messiah complex—and it’s easy to level the same accusations at Parker. When the final credits come up, his name is four of the first five we see on screen. It’s hard to separate the vanity from the project, but it’s also a real achievement for a filmmaker of colour, putting him in the company of Tyler Perry and Spike Lee.

Parker depicts Nat Turner as “the one.” Physical marks he’s carried since birth set him apart—he’s prophesized to be a leader among the plantation slaves. He accepts this without question, learns to read, and becomes a preacher. When times are tough, his white slave owner Samuel Turner (Armie Hammer) takes him to other plantations to speak to the slaves, to quash resistance and calm them with the word of God. The tour also reveals to Turner the horrific conditions on other plantations, strengthening his conviction to fight back. He also finds time to rescue a young woman, Cherry (Aja Naomi King), who he falls in love with, and to antagonize a local slave-hunting villain, Cobb (Jackie Earle Haley).

While Parker has a knack for where to put the camera, and some striking imagery—blood bubbling out of an ear of corn and a gorgeous eclipse—the editing is choppy and many of the supporting characters barely manifest. There’s something pulpy and slightly rushed about it. This is much more a straight ahead revenge thriller than the art house style of Steve McQueen’s 12 Years A Slave, but with a far more serious and reverent tone than, say, Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained.

Parker chooses the tiresome rape-of-a-woman-as-heroic-motivation trope, which feels especially awkward for obvious reasons, but it would be cliched either way. The women in this film get to be adoring and supporting, but not much more.

But when the revolt does come, there’s a satisfying inevitability about it. The politics of these sequences can’t be ignored—black men using axes, knives, and muskets to kill whites, men, women and children, some of this is explicitly shown and some of it implied. This isn’t something I can ever remember seeing in a film—every white person is an antagonist, at best ignorant and worst hateful. It’s a potent vision, and it’s easy to see how some racist factions would be offended.

While the film is deeply flawed, there’s no denying its volatility and power.