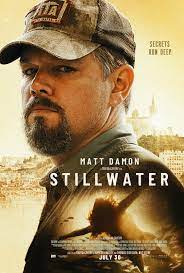

Directed by Tom McCarthy | Written by McCarthy, Marcus Hinchey, Thomas Bidegain, and Noé Debré | 139 min | Crave

Tom McCarthy is a filmmaking wonder. He’s responsible for the lovely indies The Station Agent, and The Visitor, the Oscar-winning procedural, Spotlight, and the terrific recent family movie, Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made, and he’s also an actor.

His new feature is loosely based on actual events — loose enough to avoid legal action, if not the understandable anger of Amanda Knox. It’s a compelling, mature potboiler, the story of a father digging into the case of his daughter, imprisoned in Marseilles for a murder she says she didn’t commit.

Matt Damon does extraordinary work here, reaching the kind of easy truth his acting hero, Gene Hackman, achieved on the regular. He’s Bill Baker, an unemployed Arkansas roughneck and widower who travels to France to visit his daughter, Alison (Abigail Breslin), who’s been in jail for years. She claims to have a lead on the man who she says is responsible for the killing, and when her lawyer won’t get involved Bill steps up. This despite speaking not a word of French.

Damon’s Bill is a deeply complex man, and while Damon himself is typically sympathetic — one of his many movie-star powers — his Bill is far from immediately likeable. He’s god-fearing, hardworking, and devoted to his daughter, even as she’s unsure about his ability to commit given his troubled past. He’s also coarse and single-minded to a fault. We get his frustration with bureaucracy and legalese, but we also see the occasional flash of the Ugly American, his righteousness and sense of justice clashing with the complex, multiethnic reality of the community he’s exploring. With the filthy baseball cap he almost never takes off and his backpack slung over one shoulder, you see the armour this guy wears to manage the weight of his life, the guilt that he was never there for Alison, which might be why she’s where she is.

The film is refreshingly non-judgmental, leaving it up to us how much we go along with Bill’s agenda, while he operates as a living, breathing allegory for American foreign policy. If this was a different kind of movie — say one starring Gerry Butler or Liam Neeson — we’d be urged to revel in Bill’s strong-arm solutions to his problems. Here, he’s undercut by his own narrow vision. It’s surprising his investigations go anywhere.

Fortunately for Bill, he has help from a local named Virginie (Camille Cottin), a theatre actor and single mother (of Maya, essayed by the excellent Lilou Siauvaud), who takes pity on him and offers to be a translator, parsing details from others who may have information to share. As Bill gets closer to Virginie and Maya, this awkward, unexpected family forms and becomes the heart of the movie. The question lingers in the air: Will Bill’s need to mete out justice for his daughter destroy the good thing he’s building here?

Stillwater tells the kind of tale that these days tends to be told by miniseries, streamed over six hour-long episodes. I’m not convinced that kind of approach wouldn’t have served this project better than a two-hour-19-minute thriller, one that stumbles a bit in the home stretch with plot holes that may have been filled by an even longer cut.

Even so, the picture is never less than gripping, thanks to McCarthy’s gift with his actors and an unerring instinct for tone and suspense.