The event of the year for the Atlantic Canadian cinephile — the FIN Atlantic International Film Festival — brings the world to Halifax every September.

This year, of course, is a little different. The entire festival is online, which is a double-edged sword for the film lover.

We get access to the full program on our computers in Atlantic Canada, so long was he have decent internet — which, unfortunately, isn’t everywhere — but people who live outside the HRM who in other years wouldn’t be able to come in for the event now have a chance to see the festival films.

What we won’t get is a lot of buzz or a sense of community. Nor will we experience the films with the big screen and the big sound. I’ve already heard from some in the local film community who’ve been a little underwhelmed at the idea of an online festival. For some, in-person participation is an essential part of the film festival experience.

The FIN program still has plenty enough for me to look forward to, and that’s even in comparison with the Toronto International Film Festival program, this year available online across the country. You can see my reviews here of the films I was able to see at #TIFF2020.

If you’re considering seeing films at FIN this year, I’ve had the good fortune of seeing a few titles in advance. My reviews are below:

For awhile now Taylor Olson has been building a career in Nova Scotia as an actor to watch, and as a burgeoning writer — he and his partner Koumbie were in the FIN Screenwriters Development Program with me in 2018. This year he’s the king of FIN, acting in five short films at the festival: Here to Help by Tim Beers, Beer Bowl by Tim Mombourquette, Phone Jack by Drew Meade, Wooden Nickels by Drew Meade, and The Death of Winter by Latonia Hartery. He’s also acting in two others, Inceldom, or Why Are The Angry Men Angry, which he also directed, and Keep, which he co-directed with Koumbie. And he produced one more, Disco Apocalypse, by Kevin Hartford.

That would be a full and impressive plate on any year, but in 2020 Olson also has Bone Cage, which he adapted from Catherine Banks’ Governor General-award winning play. He directs, and is the lead, Jamie. It’s his first full-length effort as a filmmaker, and he makes it count.

(Full disclosure: I saw a rough cut of the film, and offered my notes on it to Olson — so I have a connection to this project that may prompt you to take my review with a grain of salt. Feel free.)

Bone Cage is about a young forestry worker in rural Nova Scotia. In Olson’s own words to the CBC, his Jamie has a duality — he’s a hard case, someone who’s living up to the sometime violent expectations of men in his community, while also in touch with some essential, vulnerable part of himself that threatens to slip away as he clearcuts the local woods with enormous, vicious machines. After he shuts them down he finds the animal victims of his destruction in the ruined landscape.

Back home he’s engaged to the loving Krista (Ursula Calder), while his half-sister, Chicky (Amy Groening) keeps an eye on him, but also doesn’t trust him to be a decent husband. This while their father, Clarence (Christian Murray) is in a permanent state of grief over a dead son. There’s a subsumed rage and resentment in most of the men on screen — frustrated by the lack of choices in life. Only Jamie seems to really understand the cost of being stuck here, the price it will exact on his future.

Olson the actor makes Jamie his own, like the restless grandchild of Jack Nicholson’s Bobby Dupea in Five Easy Pieces, but seeing even fewer outs. This while Olson the director makes a host of interesting stylistic choices, with DP Kevin A. Fraser and editor Shawn Beckwith, from tasty overhead drone shots to dreamy interjections, moments of human connection. Bone Cage should be counted with the recent Werewolf and Murmur as a strong first effort from a promising Nova Scotian filmmaker, illuminating a fragment of real life in this province.

Darrell Varga’s new documentary provides a pleasing, meandering look at the cultural impact of bread through the eyes of poets, artists, historians, and bread scholars — yes, there are such people, and they’ve got a basket full of insights into the importance of bread, especially to immigrants and migrant peoples.

We hear about the history of baking, the politics of community bread-making, and the impact of white bread on America, all leavened by scenes of bread-making and archival footage linked by Lukas Pearce’s soundscapes and walking baselines. Bread In The Bones is much more, dare I say, organic than Michael Pollan’s ingredients-based look at bread on his Netflix show, Cooked.

It’s occasionally a little hard to keep track of where we are in the world, maybe intentionally driving home the universality of the film’s subject as we bounce between interviews in Paris, Sofia, Belgium. Montreal, New York, and Vermont. The film works best when it provides a platform for passionate advocates to share their expertise on bread as more than even the staff of life.

Highlights include artist and bread-maker Lexie Smith, oven-maker Stu Silverstein, historian of French bread and culture, Steven Kaplan, and especially late craft historian and beloved NSCAD prof, Sandra Alfoldy — to whom the doc is dedicated.

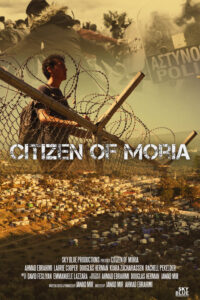

This week we heard about the fire at Moria, Greece’s largest refugee camp, dislodging 13,000 people. Originally built to accommodate 750, then expanded to house 2500, it’s actually held almost 10 times that number for years.

This is a first-hand document of Moria through the narration and camera of Afghan filmmaker Ahmad Ebrahimi, who along with Canadian filmmaker Jawad Mir shows us what life at the camp has been for the past four or so years. Ebrahimi is a charismatic and forthcoming guide through daily life in the camp, the occasional violence and regular protests on the island of Lesbos. The poverty and deprivation is about as difficult as you can imagine such a place might be.

The filmmakers also interview volunteers and international aid workers who provide their own perspectives on what’s happening with the asylum seekers. Ebrahimi also fosters and develops his interest in film, the connections he makes with educators and supporters help increase his chances of getting out, finding a home in Europe or Canada, and reuniting with his wife and children who he left behind in Afghanistan.

Through one refugee’s perspective we get a genuine sense of the experience of them all. It humanizes a story that’s easily shrouded in statistics and images taken from a distance of people in boats bobbing on the Mediterranean.

Ariel Nasr is a Halifax-raised, Afghan-Canadian documentarian whose award-winning films Good Morning Kandahar and The Boxing Girls of Kabul announced him as a voice in non-fiction film. The Forbidden Reel is not only his longest effort, it feels the most personal.

It tells the story of Afghan Film and the archivists who saved 2500 reels from the Taliban, but it also serves as a brief history of Afghanistan through the past 50 or so years through footage from those saved films. We hear stories of the filmmakers who lived and continued to work through Communism, the Mujahideen, and even the arrival of the Taliban.

Though Nasr interviews many of the key filmmakers — including Ibrahim Arify, Engineer Latif Ahmadi, and Siddiq Barmak — artist and archivist Mariam Ghani, who through her own investigation into Afghan Cinema provides a deft historical overview, and even a movie star, Yasmin Yarmal, the real star of the show is the footage from the rescued films. It reveals a rich and varied culture, 180 degrees from the stereotype of the war-torn nation.

Gwen (Emily Bridger, also script writing) shifts uncomfortably near a playing child, waiting in the St John’s airport for her sister, Janet (Marthe Bernard), to pick her up. She’s joined by the third sister, Kay (Rhiannon Morgan). It’ll be a wintery wedding for Jan, the reason for the sisters’ reunion. Fingers crossed their estranged mother also shows up, but who really knows for sure?

Actor-turned-director Ruth Lawrence’s first feature is a terrifically cast dramedy — the three leads are entirely plausible as sisters — full of delightful moments of truth and more than a few laughs.

Gwen is the centre of the action — having escaped Newfoundland for Toronto she’s found peace, but what’s she lost? Ex-boyfriend Tom (Andy McQueen) seems a catch, with a nice ride and property out at Portugal Cove, so why won’t she take the chance on him? The fear of commitment rides higher and louder in Kay, who refuses to take responsibility for her own daughter in the care of Aunt Maureen (Kyra Harper). This while Janet might be getting married as a counter to those expectations of the sisters’ restlessness.

There’s a scene in the third act where it feels like emotional punches are pulled — I wanted more catharsis in what happens between the sisters, but Bridger’s sense of character and authenticity carry the day.

Writer-director Jillian Acreman’s feature debut is ambitious as hell. It’s a low-budget, retro-futurist science fiction picture shot in New Brunswick — the story of a brilliant scientist, Pillar (Bhreagh MacNeil of Werewolf), drafted into a mission to Mars. In this near future society there’s no refusing this “honour,” as much as Pillar might like to. Instead, she keeps it a secret from friends, her lover (Hailey Chown), even her father.

As a terminal illness allegory, a one-way trip off-world is a unique scenario and it works. At first Pillar makes her choices seem at least reasonable, but as she suffers while bearing up to her secret knowledge, it doesn’t take long before the consequences of those decisions reveals her selfishness. The tension bubbles around whether she’ll end up admitting her fate, and later around whether she can change it.

It’s a lot to ask of your audience — to stick with a painfully unlikeable lead who compounds bad decisions with worse, riding on the hope her vulnerability is enough to gather our sympathies. If Queen of the Andes leaves a bitter aftertaste, it’s not one you’re likely to forget.