Carbon Arc Independent Cinema’s most recent season has concluded.

As a programmer I am grateful to have been able contribute to the screening selection, though as a volunteer I wasn’t able to see every film that showed. The ones I missed, disappointingly, include Rafiki, Capernaum, Styx, Birds Of Passage, and Ziva Postec: The Editor Behind The Film Shoah.

Please find reviews below for the films I was able to enjoy, including a truncated version of my review of the Best Foreign Language Oscar-winner, Roma, which Carbon Arc screened multiple times in February.

Carbon Arc director Siloën Daley has one more trick up her sleeve this spring: AVX8: The Animation Festival of Halifax, running from May 9-11. Please go here for screening information and advance tickets.

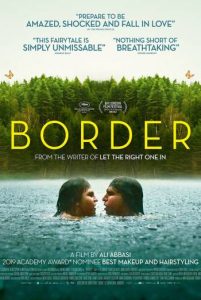

Border

A Swedish film from director Ali Abbasi and screenwriter John Ajvide Lindqvist, who famously wrote the modern vampire classic Let The Right One In. This picture is another supernatural fantasy, but with a different flavour.

Tina (Eva Melander) works as a Swedish customs agent with a gift for telling if travellers have evil intent. Her heavy-browed look is matched by someone she pulls aside, Vore (Eero Milonoff), with whom she has more in common than just the physical. He suggests to her they’re trolls, and they’re fundamentally different from the human beings with whom they live. She starts to believe him, but does she trust him?

It’s a peculiar, touching romance with a surprising thriller element, shot with a care to grit and realism, the unusual stylistic bedfellows creating an interesting tension as they rub up against each other. And speaking of rubbing, Border also includes what might be the most unusual sex scene in cinema history, and that’s saying something.

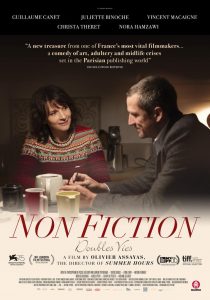

Non-Fiction

Olivier Assayas’ most recent films have been exceptional, even given the French writer/director’s extensive and distinguished filmography. The Clouds of Sils Maria and Personal Shopper are both wonderful, both concerned with the division between the public and private, the attention of celebrity, and the shadow of mortality. With this effort, entitled Doubles Vies in French, Assayas takes a turn to a very Parisienne brand of dry comedy, that of intellectuals arguing in small groups over wine about work and social issues while they’re secretly unfaithful to their spouses. I didn’t find it nearly as engaging as the two films mentioned above, but it’s still an altogether pleasant way to spend a Friday evening.

Alain (Guillaume Canet) is a successful publisher who worries about the erosion of the print world by the digital. He also has a formerly high-selling novelist, Leonard (Vincent Macaigne) who has a new semi-autobiographical book, but Alain isn’t interested. Alain’s wife, Selena (Juliette Binoche), an actor on a TV series, is sleeping with Leonard. Meanwhile, Alain’s sleeping with his much younger marketing guru, Laure (Christa Théret), who espouses a bleak, or exciting—depending on your perspective—digital future.

And that’s the crux of it. Cue a lot of discussion about the future of books, of writing, and of French culture, with intermittent bed-hopping. It’s charming and occasionally funny, well-acted, and even meta in its perspective, with an added soupçon of the ephemeral.

Never Look Away

Another Oscar-nominee for Best Foreign Language film—recently renamed the Best International Feature Film award—this one comes from German filmmaker Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, whose debut was the remarkable The Lives of Others. Here he reunites with the star of that picture, Sebastian Koch, who this time plays a haunted Nazi obstetrician, Seeband.

At the heart of this epic drama is Karl, who we follow from age five, pre-WWII, to his mid-30s in the 1960s, as an adult played by Tom Schilling. As a child he’s especially fond of his aunt, Elisabeth (Saskia Rosendahl), but she’s got an “artistic temperament,” which is diagnosed as a mental illness.

At the beginning of the war she’s sent away to an institution, under Seeband’s care, from which she never escapes. But in the time they had together, she’s inspired young Karl with her perspective on the world, and the film tracks Karl’s talent for painting as it’s channeled into the propaganda needs of the East German state until he (and his wife Ellie, played by Paula Beer) escape to the West and he locates his own creative voice, with encouragement from the early-’60s avant garde art scene in Dusseldorf. The key connection to his past is Ellie’s father—he’s revealed to be Professor Seeband, but neither Karl nor the Professor seem to be aware of how they are connected by Seeband’s treatment of Karl’s aunt, at least not consciously. But later on, as Karl finally manifests his potential, there’s a reckoning.

For a film that tops three-hours, Never Look Away is startlingly pacy. At this length it would be hard for it not to be episodic—and some of those sections are more successful than others—but overall the film delivers a serious emotional payload. The final act provides a lot of narrative space devoted to Karl’s evolution as a painter—it’s a kind of cinematic thrill in creation that, for instance, the recent At Eternity’s Gate failed to communicate.

Where it gets a little obvious is in the end of the first act, where Karl is indoctrinated into the socialist art school and falling in love with Ellie—the sex scenes are bracing, but the romance between Schilling and Beers is a bit damp, further moistened by a too-insistent score that goes out of its way to tell us how to feel, when the film should simply trust its capable performers and screenplay. That said, that final 30 minutes are so satisfying, it’s easy to forgive those few minor quibbles earlier on.

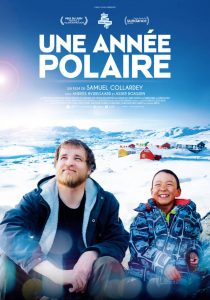

A Polar Year

I couldn’t help but compare this film to The Grizzlies, a Canadian film I saw last week about a white teacher who goes to a small community in Nunavut and teaches the kids there how to play lacrosse. With The Grizzlies, while I admired the location cinematography and the performances of the largely indigenous cast, the white saviour trope was a tough pill to swallow. Despite its parallel storylines—in A Polar Year a white character from Denmark moves to an indigenous community in Greenland to teach children—A Polar Year feels much more open and successful on most fronts.

Samuel Collardey is a French filmmaker whose metier is documentary/dramas, a blurred line between the traditional documentary we’re used to seeing here in North America, and a feature film. So, even while all the characters here are actual people, one gets the regular sense that Collardey has staged scenes and reenactments with his subjects. There’s an extra layer of artifice, and it’s tough at first to trust what we’re seeing.

In this case, the teacher is Anders Hvidegaard, and he arrives in Greenland without much understanding of the culture he’s getting in to. But at no time does he feel his job in the remote Greenlandic community is beyond just teaching the children, and the film is genuinely about the locals—we may see them through a western lens, but not necessarily through Anders’ eyes. The boy, Asser Boassen, with whom Anders connects, is as much a protagonist as the teacher is. Asser is eight, and wants to be a hunter like his grandfather, but there are obstacles to that traditional way of life, which we understand more clearly as we go along. A Polar Year also functions as a gorgeous travelogue. Collardey uses drone cinematography to capture the rugged beauty of the landscape, especially effective during a trip into the mountains to look for polar bears.

While I still have concerns about the accuracy of what we’re seeing, if not the authenticity, there’s a sweet open-mindedness at play here that’s to the film’s credit.

Roma

Mexican auteur Alfonso Cuarón (Children of Men, Gravity) tells a semi-autobiographical story, a portrait of the woman who raised him, the housekeeper in his upper-middle class home in suburban Mexico City. Shot in black and white, Cuarón locks down his camera and pans around rooms, streets, and the interior of cars, as people go about their business. His reluctance to shoot up close means his characters are often a little lost in their environments, and us with them.

But what a place to be lost in!

Cuarón, who also lensed his picture—no Oscar-winning DP Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki on the project this time—creates a feast for the eyes, so much gorgeousness to take in. His recreation of Mexico in the early 1970s astonishes—favouring wide-angle imagery to create enormous scope and scale—while his character focus, a single, fracturing family—a woman (Marina De Tavira) with four kids and an absent husband, and their housekeeper, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio)—takes awhile to establish, but it pays off in a big way as we go along.

The film is anything but lethargic, and the story of Cleo and her life as an essential part of the family, while still being their servant, is fascinating. This isn’t simply a formalist exercise, or a purely nostalgic one. It’s a domestic epic.

Cleo spends her days cleaning up after the family, looking after the children while she lives in a small apartment in the back of the house with the cook. When the patriarch disappears and the mother starts to fall apart, Cleo becomes even more important to what remains. She spends her free time with a young man, a martial artist who fashions himself as a revolutionary, but when he realizes she’s pregnant, he disappears.

At its heart, Roma is a touching ode to mothers, but it takes time coming to that conclusion, in an immense backdrop of class, politics, youth culture revolt, city life, and family vacations. Cuarón meanders a little in places, indulging in sequences that don’t add up to much—here I’m thinking of a scene with a burning forest and a man in a monstrous costume—which have more in common with Fellini’s Roma than anything Cuarón’s done previously.

But just when you start to think this is all just an exercise in keeping the film’s lead on the edge of the frame while the filmmaker indulges in his gorgeous but rambling trip into his personal history, Roma hits you with a couple of potent, moving scenes, where your patience with the set-up will be entirely paid off.