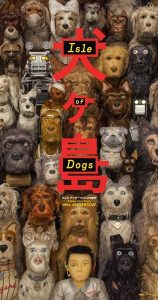

Directed by Wes Anderson | Written by Anderson from a story by Anderson, Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, and Kunichi Nomura | 101 min

The new Wes Anderson is as brilliant and idiosyncratic as anything I’ve seen in his peculiar cinematic output. It also has moments where I was left befuddled, bemused, and maybe, once or twice, even slightly bored. Isle Of Dogs contains multitudes.

It’s a stop-motion animation, Anderson’s first since Fantastic Mr Fox, which is far from my favourite of his joints. When I saw that film following years of people talking about his twee preciousness and not really getting the complaint, I finally understood. I can’t remember who said it, but someone wrote that his need to exercise total control in his stories was crystalized with animation, but the sense of life and spontaneity brought by his collaborators in live action, from his actors especially, felt diminished, and so the overall effort was parched. That was my takeaway, too.

That’s not really a problem here. This feels like far more of a group effort—aided by a sprawling cast of voice actors—and feels more mature. It’s also quite a bleak vision, exploring fascism and totalitarian thought, which like his last picture, The Grand Budapest Hotel, tends to cut the sugar.

It takes place in a fictional Japanese city in the future as seen from the 1960s, where Mayor Kobayashi (voiced by Kinuchi Nomura, who also has a story credit) has engineered a way to get rid of dogs, exiling them all to a literal island of garbage off the coast. There they roam in packs, starving and suffering from debilitating Dog Flu and Snout Fever—a genuine post-apocalyptic scenario. The cast of dog voice actors includes Anderson favourite Bill Murray, as well as Bryan Cranston, Jeff Goldblum, Bob Balaban, Edward Norton, Scarlett Johansson, and Tilda Swinton, with Japanese actors including Ken Watanabe, Akira Takayama, and Japanese-Canadian, Koyu Rankin, as Atari, a young man who flies to the island looking for his missing dog, Spots (Liev Schrieber), inspiring a foreign exchange student, Tracy (Greta Gerwig), to lead a movement against the corrupt municipal government.

The film is jam-packed with Anderson’s usual detailed fussiness, filling the frame with eye-catching visual treats, steam-punk mechanics, and the particulars of making poisoned sushi. I loved that the stop-motion animation transformed into black and white 2D animation whenever the action is viewed on monitors.

This is another one of Anderson’s misfit family stories, with the children (and animals) knowing some deep truth about life that has escaped most of the adults. It falters here and there in its narrative pacing, and Anderson’s typically arch screenplay tends to keep us at an amused but arms-length distance from the characters for whom we’re supposed to care about. That cool tension is nicely counterbalanced by the adorable formality of his four-legged leads, their dignified intelligence and fierce, touching loyalty to their human masters, as well the frequent, teary close-ups. Even as the film suffers from occasional lulls, it offers a banquet of imagination.

Now, a little about the conversation on whether the film is an example of egregious Orientalism. I’ve been wrestling with the issue in my head and reading as much as I can on the subject.

Anderson has always felt free to borrow from cinema of other cultures. His Isle of Dogs is an undeniably western perspective of Japanese culture, art, and film. I recognize it has problems on this front.

Some of the voices I’ve read have tried to defend it by saying it’s a fantasy land, a look inside Wes Anderson’s head and his particular, expansive vision of the world, just as The Darjeeling Limited (earning its own accusations of cultural tourism) about India and The Grand Budapest Hotel regarding Eastern Europe. So, does that make Isle Of Dogs a 21st Century Mikado, and if so, is such a thing even defensible?

Well, hold up a second. Consider the way Anderson uses language in the film.

Almost all the humans are Japanese characters, and they speak Japanese, much of which isn’t subtitled, though some is translated (by a character played by Frances McDormand). All the dogs’ barks are “rendered into English,” as is explained early on by a helpful caption.

I think the film’s immediate addressing of the language barrier, and its only partial willingness to help those of us who are monolingual bridge it, is an interesting choice. Some have said it exoticizes the characters in their own environment, but I think the opposite is true. It’s a constant reminder for Western audiences that we are the visitors here, as is Anderson himself—it’s a subtle acknowledgement of his outside lens. It’s also a tacit nod to Anderson’s affection for both the sound of Japanese language and of its cinema.

Of course, an affection for a culture is no excuse for cultural stereotyping or appropriation, if that’s what’s going on here.

I’m also interested in Anderson’s collaboration with Japanese talent. A number of the voices in this conversation charging cultural appropriation discount the contribution of Japanese writers and actors to the project, or just complain how few people of Japanese heritage participated in the film. It’s reductive to ignore Anderson’s efforts at bringing authenticity to the piece, and insulting to those artists who participated.

I guess I have a question: If you’re a creator in any storytelling medium, and you choose to set your story in another culture, what does it take to do it? Last year’s Kubo And The Two Strings got a pass, as did Martin Scorcese’s Silence. But neither Anderson’s approach, nor his consultation or collaboration, will wash in the same way. Is that because the culture has changed in the past six months, or because this film is more egregious than those other examples? It could be a little of both.

Hollywood’s appalling history with whitewashing and outright cultural stealing needs to be left in the past, but no one’s yet written a rule book on how stories like this get told. Maybe we’re heading to a point where only people from inside a culture will be able to represent it, and maybe we need to be there for awhile… but hopefully, somewhere between these poles, the future holds a middle ground of deeper understanding.

Isle Of Dogs I’d say it has its issues, but it’s also too interesting, too delightful, to ignore. (Except maybe by cat people. )