I haven’t read Louisa May Alcott’s semi-autobiographical book, though I know a fair amount about the story: a tale of the four teenage March sisters in Massachusetts during the American Civil War, growing up and missing their father who’s off fighting—the mature eldest, Meg, the tomboyish writer, Jo, the shy pianist, Beth, and the prim artist, Amy.

The films are probably best described as coming-of-age dramas, stories of friendship, sisterhood, and young love. There’ve been plenty of other versions, including a solid recent BBC mini-series (starring Maya Hawke, Angela Lansbury, and Emily Watson) available on CBC Gem, but I’m focusing on the best-known, available cinematic adaptations. A review of Greta Gerwig’s 2019 take will follow soon.

Watching these films in quick succession is a lot like watching all the versions of last year’s A Star Is Born—the material has the real potential to be told through a progressive lens, though all the pictures end up saying a lot about the era when they were made.

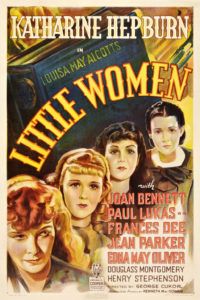

1933 | Directed by George Cukor | Written by Sarah Y Mason, Victor Heerman, and a host of contributing writers | 115 min | VOD

Cukor, who famously also directed The Philadelphia Story, Gaslight, and A Star Is Born (1954), brings a light, playful tone to this early feature film, apparently the third version of the book to be adapted for the movies, but the first talkie—the two earlier silents are hard to find, with one considered officially lost. Cuckor’s film is wildly entertaining, with lush costumes, sets, and a collection of solid performances—though the March sisters are all cast a lot older than the collection of teens described in the book—Katherine Hepburn was 26 when she defined the passionate protagonist, Jo. She goes big and broad and pouty here in a remarkably physical role, with lots of slapstick humour and falling over herself. As the world discovered then and in the years following, Hepburn’s a magnetic presence on screen, which makes her appealing even as her Jo is frustratingly selfish and narrow-minded.

The other sisters rapidly slip into the background by the third act when Jo moves to New York to become a governess, and gets friendly with much older Professor Bhaer (Paul Lukas, channelling Peter Lorre). It remains a pretty conservative vision, with the element of their so-called “poverty” soft-pedalled—they’re wearing different dresses in every scene—and Jo’s success coming in tandem with finally falling in love with an older man and a lot less of the frustration that she “wasn’t born a boy” we see in other, later versions. Her journey leads to a kind of conformity—she gets to be the writer she always dreamed of, but her youthful thoughts of rebellion and independence where she didn’t want to be tied to a man soften to include that possibility.

Other elements that make it more engaging as seen from the present day: Jean Parker as Beth is weirdly the spitting image of Celine Dion, while Douglass Montgomery as Laurie, the neighbour’s son who sets his hat at Jo, looks and sounds a lot like Martin Short’s Ed Grimley.

1949 | Directed by Mervyn LeRoy | Written by Andrew Slot, from the screenplay by Mason and Heerman | 122 min | VOD

The first difference you’ll notice in this first colour version is that Amy (a blonde Elizabeth Taylor) is no longer the youngest, it’s Beth (Margaret O’Brien), and Christmas is a much bigger deal, with more carols and snow and festive energy. Otherwise it’s much the same—Aunt March (Lucille Watson) lords her wealth over the sisters and their mother (Mary Astor), and the girls indulge Jo her dream to be a writer and create fantasy universes—it’s as much based on the 1933 screenplay as it is the novel, with some scenes, especially in the third act, the same as the ’33 film, word-for-word. A scene where Jo burns the back of her dress is fresh, and a lot more happens in yard outside the homestead to capitalize on the enormous sets.

June Allyson as Jo is solid, but nowhere near as much fun as Hepburn, nor does she get to show the same breadth of her character’s growth. It also sounds like she’s been a three-pack-a-day smoker for years—and at 32 in 1949 she may have been—while Peter Lawford as Laurie is stiff as a board, and Rossano Brazzi as Professor Bhaer a lot more hunky. Both Taylor and Leigh shine as Amy and Meg, providing characters a lot more vivid here than in the previous film. Overall, this is a much less wordy picture than the ’33 version, but a lot more cheesily sentimental, though weirdly the death of a main character happens off camera.

The classicism of the 1860s is much more apparent here, which pleasantly expands the story’s scope, but so is the baked-in sexism of 1949—at one point Astor gives a speech about the plans she has for her daughters, that they be “useful and pleasant,” and nods knowingly when Jo says she’ll never get married. Though, in the final assessment, she may not—the conclusion is ambiguous.

1994 | Directed by Gillian Armstrong | Written by Robin Swicord | 115 min | now on Netflix

This version’s a breath of fresh air after the safe conventions of the older films. It’s written and directed with a lot of nuance by the Australian indie filmmaker Armstrong (Charlotte Gray, Oscar and Lucinda) and Swicord, who’d go on to script The Jane Austen Book Club and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

The first distinct improvement is that the girls are convincingly teenagers, with Winona Ryder (23 at the time) a wonderful Jo, theatrical and prone to anger, but not a scene hog. The others are terrific, too: Trini Alvarado as Meg, Clare Danes as Beth, and a very young Kirsten Dunst as Amy, who is replaced by Samantha Mathis later in the film. Amy’s self-centredness makes a lot more sense given she’s once again the youngest and likely the most spoiled, though Mrs March is played by a very modern Susan Sarandon, who offers thoughtful guidance to all her daughters. A plethora of kittens in the house is another plus.

We also get a real sense of what women had to put up with at the time—fainting caused by corsets, the patriarchal notion that education was wasted on them, and the fact women simply didn’t have the rights or freedoms of men.

The script is streamlined to make Laurie aka Teddy (a fresh-faced Christian Bale) a much bigger part of the sisters’ world, and minimizing the presence of Aunt March (Mary Wikes) and Mr Lawrence (John Neville), while Eric Stoltz as John Brooke gets a scene or two to win over Meg. When Friedrich Bhaer finally appears, he’s played by Gabriel Byrne, and he’s a charming and plausible romantic interest for Jo, despite their age difference—though their connection is where the film gets the most soppy.

A couple of surprising, fiery scenes between Bale and Mathis clarify both their characters and chemistry, and all of a sudden their romance becomes a core part of the story. In the previous films you never got the sense that Laurie actually got over Jo, that maybe Amy was just a substitute. Not here. The conclusion, including the detail about turning Aunt March’s house into a school, gives the film the right ending and brings it back to the book.

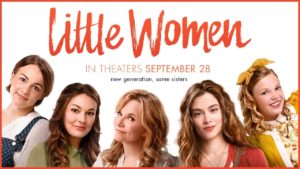

2018 | Directed by Clare Niederpruem | Written by Niederpruem and Kristi Shimek | 112 min | Netflix

This contemporary retelling of Alcott’s novel arrives looking like a Hallmark movie. Structurally, there’s promise: Jo (Sarah Davenport) is the… housekeeper? Dog walker?… for Aunt March (Barta Heiner), while she’s plugging away at her writing, but she’s 29, in college, and isn’t sure she has the talent required to make it. She catches the eye of a handsome professor named Freddy (Ian Bohen) who offers to be her editor, though you’ve got to wonder about his ulterior motives. He tells her she’s much more interesting than her gothic fantasy stories. We’re then treated to regular flashbacks of Jo’s family life with sisters Amy (Elise Jones/Taylor Murphy), Beth (Allie Jennings), and Meg (Melanie Stone), with a largely silent mother, Marmee (Lea Thompson), and the absent father (Bart Johnson), an Army doctor overseas. This could work, with a little zip to the direction and a less expositional script. That’s not what happens.

This version of Little Women isn’t overtly a faith-based film, but it is distributed by Pure Flix, the conservative Christian company, and the implicit message is clear: Despite the present-day setting, almost everyone is white and well-scrubbed, a 1950s midwestern fantasy of what America is like. When Meg goes to a few high school parties, we’re made to understand fast food and slow dancing is much better than drinking and casual sex… and, naturally, Jo hates New York and the big city life, because everything good and wholesome in America happens in small towns. It doesn’t help that aside from Lucas Grabeel as Laurie, the cast is stuffed with a typical bunch of charisma-free, square-jawed dudes.

At no time are we ever convinced by Jo and Laurie’s relationship because it isn’t fleshed out. The film makes Jo’s anger around Meg’s marriage seem insane, because it isn’t based on anything but her belief that her sisters shouldn’t get married—it’s just mock outrage in advance of the message that weddings are pretty and that Jo will come around. Even the flashbacks are hard to keep track of, offering a checklist of plot developments that don’t feel especially earned.

This version doesn’t warrant a look, even from completists.