Along with the Bradley Cooper film, here’s a look at the predecessors, the three times stars were born in the past. Dialogue and scene structures are frequently repeated, so it’s interesting to observe what’s been retained and what’s been discarded. Some spoilers to follow about the older films, but not of the 2018 edition.

1937: Directed by William A. Wellman and Jack Conway | Written by Wellma, Dorothy Parker, Alan Campbell and Robert Carson | 111 min | On Demand

In an opening of the first film (available on YouTube) that feels very meta, even now, we first see script pages from the movie we’re watching, describing the action we’re about to see. This is a movie about movies.

The Bodgett residence in North Dakota, with young Esther Blodgett coming home from the movies. “Norman Maine’s one of the best actors in pictures,” she says.

Aunt Maddie: “You and your movies, it’s all you think about. You shouldn’t be allowed to go to them at all if you’re asking me.” Granny: “To bad I was so busy in the kitchen, I didn’t hear anybody asking you.” Aunt Maddie: “Of course, no one ever listens to me.” Granny: “They do if they’re within 10 miles of ya!”

That’s totally Dorothy Parker dialogue. Sharp as a needle.

Esther freaks out saying she’s going to Hollywood and one day, no one will laugh at her. She’s on a mission from the start, and determined. As the song says, her ambition makes her look pretty ugly, but it defines her. Her father says, “If it was spring I’d say give her a good dose of sulphur and molasses.”

Granny talks about being a frontier woman with her husband: “We burned in summer and froze in winter, but we kept on going, because we were doing what we wanted to do!” and then: “Every dream you go after you pay the price in heartbreak.” Granny gives Esther the money to go to Hollywood: “I was only saving for my funeral, and now I don’t think I’m ever going to die.”

That opening scene between Granny and Esther is astonishing. It’s a terrific jumping off point for the story.

Of course, this is 1937, so things are a little soft in places. But Maine is a genuine alcoholic, getting into trouble all the time. Off screen he steals an ambulance. The studio head is played by Adolphe Menjou, who I recall from a film he made 20 years later, Paths of Glory. He’s great in this as a man who cares for Maine, and tries to warn Maine about his drinking. Maine gives him a token that says, “Good for amusement only,” and says, “This is my epitaph.”

The film celebrates stardom while offering a cautionary tale on its pitfalls… the price you pay for your dreams. Norman is interested in Esther even though he’s married, and he’s clearly out of control. Janet Gaynor’s great in this because she’s not especially glamorous. She has a well-scrubbed ordinariness about her, which makes her midwestern optimism so convincing. She’s told, “You know what your chances are? One in a hundred thousand.” She responds: “Maybe I’m the one.”

Later she gets a gig catering at a Hollywood party, and Esther does terrific impersonations of Mae West and Katherine Hepburn while serving hors d’oeuvres.

Lionel Stander (who I recall from his role on the 1980s TV series Hart To Hart) is the studio publicist who promotes the new star, whose name is changed to Vicki Lester: “Her very walk they tell me is enough to drive men mad. She’s trained to speak and plucked and groomed.”

The package delivery guy calls Maine Mr Lester, that’s a tipping point. And when Stander kicks the crap out of Maine, that’s a real low point. But March doesn’t make Maine terribly sympathetic. The booze makes him mean.

The end comes when Vicki says she’ll give up her life to run away with her husband. He stands in the fading sunlight and says to her, “Hey, mind if I take one more look?”… a line that survives through the versions to show up in 2018.

Then he swims off to his death. I really enjoyed it when Granny shows up and gives Esther a good talking to. “You did make a bargain, and now you’re whining about it. I was proud to be the granddaughter of Vicki Lester. Now I don’t have anything to live for.”

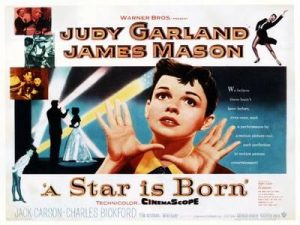

1954: Directed by George Cukor | Written by Moss Hart, based on the 1937 screenplay | 154 min | On Demand

The 1954 musical epic is probably the most critically acclaimed of these films, and it certainly impresses through its long running time, with a 178-minute version including restored scenes also available. Many critics have talked about the ways it parallels Judy Garland’s actual life and career in uncomfortably personal ways, how Hollywood packaged her in ways she didn’t like. Garland seems like she’s just on the verge of tears at all times, and that kind of tremulousness is perfectly suited to this role. It’s also a full-on musical with some amazing set-pieces, and James Mason is terrific as a man who shelves his pride for his love.

I was surprised by the sheer scale of the thing. I think that’s what I liked about this version the most… it has a fairly intimate, relatable story juxtaposed with a full-on musical, bringing forward the 1937 version and applying more of the music side of show business, but the tragic love affair is still very much a part of it. The first difference from the original is, of course, the musical elements. It also dispenses with the girl coming from a small town business. She’s already slogging it in the nightclubs when we meet her here, stoking her career as best she can.

Also, Mason is also getting under Norman’s skin in a way that feels more realistic than the previous film. Frederick March didn’t really bring much pathos to the character, but Mason is a genuinely tragic figure.

And that scene late in the running when the studio guy Oliver shows up, played by Charles Bickford, and Vicki Lester is in the hair and make-up chair, and she’s got all that black eye make-up on… she’s clearly in a rough place, and she asks Oliver what it is inside someone that makes them want to destroy themselves. Then she admits she sometimes hates him, and then she hates herself for failing him. It’s a scene of such incredible rawness—you can find it on YouTube if anyone wants to see it without committing to the two-and-a-half hour version or the three hour version, and it’s the kind of acting you don’t see often at that era, before the method. It’s the kind of on-camera honesty that wouldn’t become popular until American cinema in the 1970s. It’s almost shocking.

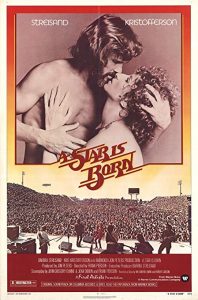

1976: Directed by Frank Pierson | Written by Pierson, John Gregory Dunne, and Joan Didion, based on the 1937 screenplay | 139 min | On Demand

The 1976 version is better than I’d been led to believe. It convincingly captures the rock and roll excess of the era with wide-angle cinematography, an army of hirsute extras, and even brings a few good tunes, and in casting Kris Kristofferson we get both a songwriting legend, a scene veteran, and a capable actor. Rumour has it Elvis was offered the gig, which would’ve made a very different film. But from stem to stern, this is a Barbara Streisand vanity project. Her character feels like a fully realized star from the start, so there’s not much of a character arc. Apparently the behind-the-scenes issues were huge, definitely a troubled production.

The first thing I liked about it was she’s not a fan of his, nor is she an ingenue. When they get married, she says, “I never thought I’d ever get married again,” which is a fairly progressive thought for 1976, I think. She’s a divorcee. She’s lived. In some ways, they’re peers, and I really liked that about it. I feel that sense of equity is what Cooper borrows.

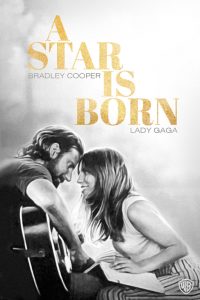

2018: Directed by Bradley Cooper | Written by Eric Roth, Cooper, and Will Fetters, based on the 1937 screenplay | 135 min | On Demand

Bradley Cooper’s taken the most from that 1976 version—with an added spiritual borrow from Mason in the 1954 edition—but he’s updated the pacing and rebalanced the storytelling.

This really is a two-hander, where both Cooper’s Jack Maine and Lady Gaga’s Ally trade leads, depending on where we are in the story. He’s the grizzled, alcoholic, pill-popping road warrior—a mid-career, mid-level singer-songwriter with a little too much Nashville in him to be Ryan Adams but too many soulful, world-weary lyrics to be Brad Paisley. He stumbles on Ally singing Edith Piaf in a drag bar and is impressed with her presence, coaxing from her the songs she writes but won’t perform for people. It isn’t long before he’s invited her up on stage to play for thousands, and naturally, she’s a sensation.

The opening act here is powerfully, emotionally on point. It’s all killer and no filler, shaking off the memories of the previous films and bringing something entirely fresh. Cooper and Gaga are great together as they fall for one another, even as Gaga is a little tentative in places, but that feeling she’s holding back something works for the character. Without the outrageous shoes and make-up of her world-conquering pop performance art, her delicacy and awkward smile is a winning combo, and her enormous voice winds up being that much more a surprising show-stopper. Cooper gives us a character we’ve never seen from him before—channeling Kristofferson’s outlaw charisma, with a gravel in his throat like Eddie Vedder’s, who the actor shadowed to pick up some of that rock star swagger.

As a director he shoots his actors the way they love, all close-ups and medium shots, keeping it intimate and saving anything wide for the sake of establishing location and aesthetics. I was impressed with how well that worked, in places even risking claustrophobia, the camera up in the leads’ grill. The only other face who makes any real impression is Jack’s manager, played by the excellent Sam Elliot with his remarkable wire-brush ‘stash. Andrew Dice Clay, Dave Chapelle, and Anthony Ramos are all fine, but are planets distant from the centre of this celestial event.

The 2018 take on A Star Is Born still manages to be faithful to the structural template that goes all the way back 81 years, but it savvily channels our current wish-fulfillment for celebrity, the Idol model, how we all secretly dream of stepping up on stage and blowing away the room with our purportedly raw talent.

If there’s a bum note here, it’s that the final act is weighed a little too heavily toward Jack, to the detriment of Ally. The cost of her transformation into a bubble-pop queen is seen only through the prism of his disappointment and jealousy, while her development as an artist goes from plot to subplot. She performs a song on Saturday Night Live, and it’s objectively awful. Is this shallow world of pop what she really wanted? The movie indicates to us through her hair-colour how she goes off-track, but it feels like a scene is missing to express her heart in this journey. The filmmakers also front-load the best songs, leaving the weakest for the closing, though that’s partly saved from a cheesy string arrangement by an intimate piano rendition.

Still, this is quality work from all involved, with special props to Cooper’s achievement in front and behind the camera. He puts the pedal down on the pacing, giving us a restless film always asking us to keep up as it leaps forward. There are moments when it challenges Almost Famous for creating an authentic story of backstage and on-stage musical myth, and that’s no small feat.