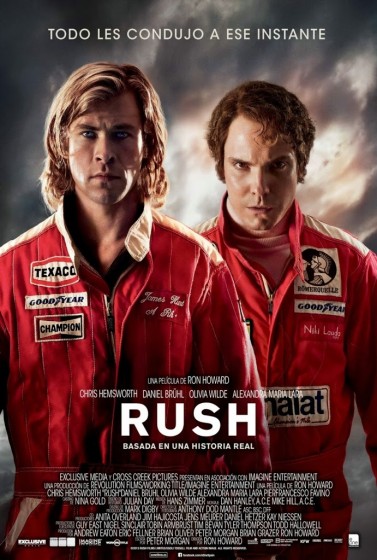

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Peter Morgan

There aren’t a lot of great motor racing movies. Um, scratch that. There aren’t any. Grand Prix? It’s over-long and hasn’t aged well. Le Mans? Other than Steve McQueen, it doesn’t have much to recommend it. Days of Thunder? They tried to redo Top Gun in NASCAR and the best moment in the movie is when Tom Cruise and Michael Rooker are racing each other in wheelchairs through a hospital ward. Driven with Stallone and Reynolds? Not so much. Talladega Nights? That might be the best one so far. But I’d argue you need to go offtrack for some real automotive excitement, in movies like Two-Lane Blacktop, Vanishing Point, Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior and Ronin.

That said, please don’t think I’m damning Rush with faint praise when I say it’s the best motor racing movie I’ve ever seen, and probably the best Ron Howard movie I’ve ever seen. Well, that second part you can take for faint praise. Howard is the king of middlebrow Hollywood entertainment—his list of quality pictures, including Splash, Parenthood and Frost/Nixon, is far outnumbered by serviceable and forgettable stuff (Backdraft, Ransom, The Da Vinci Code), the overrated (A Beautiful Mind) and the genuinely stinky (How The Grinch Stole Christmas). But for a guy who grew up on-camera, he’s one of the few who’ve carved out a long and commercially successful career behind it. And let’s not forget his first feature was a car-chase actioner called Grand Theft Auto.

Why does Rush work? Because its many moving parts are sleek, sexy and um…. oily? The true story of two Formula One drivers, the British playboy James Hunt (Chris Hemsworth—who seems to shrink when he’s not swinging the hammer) and Austrian grinder Nikki Lauda (Daniel Brühl—the Inglourious Basterds actor with added buck teeth making him a dead ringer for the real racing legend), who, during the 1976 F1 season were each others main competition on the track. And it was a deadly track at the time—more recently, post-Ayrton Senna’s death, the sport has become much safer, but back then one or two people died on the circuit annually. Lauda did not retire unscathed: in the midst of the ’76 season he was badly burned in a crash on a German course, but after only six weeks of recovery he was back racing.

In that season, Lauda was already the champion, though nobody liked him. He was all intellect, all measured risk, all asshole. Hunt was the party guy, who loved the attention and the attendant fame. They didn’t like each other but they needed each other to win. But what Rush is really about is two men learning that there’s more to life that racing in circles, more than winning at any cost.

One of the things I liked about the movie is it works without a real villain—an interesting parallel with Howard’s Frost/Nixon. (He should only do two-handers from now on.) At times, neither man is terribly likeable—Hunt berates his model wife (Olivia Wilde, rocking a British accent) with an unreserved spite, while Lauda is nasty to his teammates, his opponents, almost everyone around him besides his wife (Alexandria Maria Lara). But Hunt has charisma, and for the bulk of the movie you root for the party animal, while it’s easy to respect Lauda’s precision and self-confidence: despite being champion, next to larger-than-life James, he feels like an underdog.

And Howard and Morgan smartly make the movie more about the men than the cars. That’s not to say there aren’t thrills where the rubber meets the road—the track footage looks absolutely authentic to the era, with camera-placement on fenders, helmets and in the track-side grass—but I’d estimate we spend up to 70% of the time getting to know the characters away from the shifting and speed. There’s a great sequence in the Italian countryside where Lauda, having pissed off his ride, gets a lift from Curt Jürgens’ ex-girlfriend before he’s recognized by some fans. And we see that Hunt, despite being painted as a selfish thrill-seeker, after Lauda’s accident shows some solidarity by getting physical with a reporter who badgers the recovering driver.

Like I said, there are many moving parts here, all of which work well. This is solid Hollywood hokum, where some deep, take-home message isn’t proffered or required. It’s just great entertainment, and I wager it’ll please most, even those not generally stimulated by the pursuit of chequered flags.