This is a semi-regular segment on FITI that shines a light on a feature distinctly unloved, or underloved, and for one reason or another deserves reappraisal.

Directed by Roger Donaldson | Written by Robert Bolt and Ian Mune, from the book Captain Bligh and Mr. Christian by Richard Hough | 132 min | 1984 | Tubi, VOD, digital, DVD and Blu-Ray

Growing up, the image of Captain Bligh I had in my mind was bigger than any imagining of the British naval officer. The name was synonymous with cruelty, an irrational tyrant who inspires disloyalty. I remember a Marlon Brando film, Mutiny On The Bounty, which I’ve never seen, but this version of the famous story I watched when it came out on VHS.

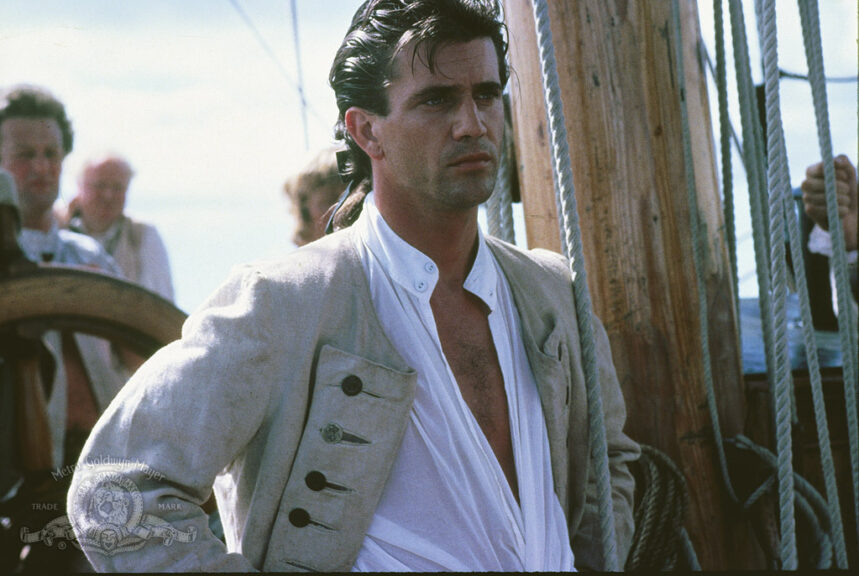

It wowed me from the start. At the time, Mel Gibson was a rising star the likes of which we don’t see often these days. Imagine a more dangerous, antipodean Timothée Chalamet, and you’re about halfway there. Arrayed around him in this movie are future stars in supporting roles — Daniel Day-Lewis and Liam Neeson — and a battery of solid character actors, including Bernard Hill, Phil Davis, John Sessions, and a very young Dexter Fletcher.

The antagonist, that nasty Captain Bligh, is essayed by future double-Oscar-winner Anthony Hopkins. What’s fascinating about his performance, and the way he’s written. is that he’s far from a cartoonish villain. He’s got plenty of bluster — Hopkins leans into his Welsh bark — but in this version he gets to tell his own story. He’s very much the arbiter of certain kinds of British colonial values, not to mention the pretensions of class. He’s ambitious, but also vulnerable, at an age where he’s afraid of never having reached his potential. He’s not incapable of compassion.

The story is told in four chapters: The first has The HMS Bounty setting sail for Tahiti to collect breadfruit to feed King George’s slaves in Jamaica. Bligh insists the ship is to round the Horn, the southern tip of South America, but it’s slammed by days of storms.

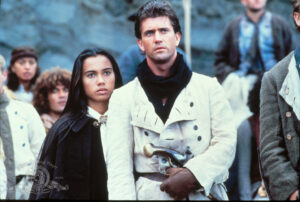

The second chapter details the Bounty’s eventual arrival in Tahiti, where the crew spend many weeks acclimatizing to the culture and embedding with the locals. After the discipline and hardships of life at sea, the “paradise” of life on the island — and a bevy of bare-breasted women — appeals to many of the Bounty’s all-male crew. Fletcher Christian (Gibson) himself, Bligh’s friend and fellow officer becomes close with the daughter (Tevaite Vernette) of the Tahitian king (Wi Kuki Kaa).

The third chapter returns the crew to sea in the days leading up to and the mutiny itself. We get the shift in Christian’s disposition and the increasing brutality of Bligh’s leadership. The final chapter is post-mutiny, the final fate of the mutineers and those who remained loyal to Bligh. The film provides both an unexpected validation and a dark ambiguity.

All of this is no less than gripping — though seen from almost 40 years later it’s hard to deny a certain colonial romanticism at work here, and of course it’s a good idea to regard any depiction of the free-love Tahitians with some skepticism.

The commitment of the actors carries the day: Neeson’s Churchill and Day-Lewis’ toffee-nosed Fryer, they’re definitely standouts, but the whole cast shine. Gibson in 1984 is practically as charismatic as he ever got — see also The Year Of Living Dangerously opposite Sigourney Weaver, and Tequila Sunrise with Michelle Pfeiffer, while Hopkins’ Bligh has to be one of his great roles — he humanizes the man while still making him very much a bastard.

Arthur Ibbetson is responsible for the vivid location cinematography, shot in French Polynesia and New Zealand. He captures both the beauty of the tropical islands as well as the existential loneliness of life at sea, framing the ship as a tiny figure against elemental landscapes and skies just before dawn or just after sunset.

Speaking of elemental, the film is improved no end by the incredible score by Vangelis. At the time the Greek composer’s synth sounds were much in demand and the movie’s genre seemed not to matter. His theme from Chariots of Fire was probably the most well-known, but can you imagine Blade Runner without his incredible score? Here the music seems to haunt the film, giving it a quality that both supersedes its period trappings while also locking it in time.

It may be set in the 1780s, but The Bounty is very much a film of the 1980s: despite the costumes and sets, the hair is surprisingly 1984. Maybe not so surprising.