It’s hard to overestimate the lasting impression of Blade Runner in my film life.

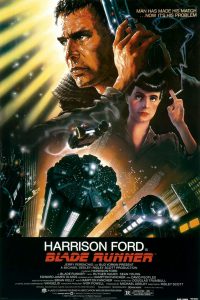

I can’t remember the first time I saw it. It was released 35 years ago, on June 25, 1982. I was not yet 12, but I must have seen it shortly after it was first released, probably drawn by the idea of a science fiction picture starring everyone’s favourite roguish star pilot and fearless archeologist, Harrison Ford. This was a very different kind of movie.

I think BR really impacted my teenage brain while I was living in London. It was the biggest city I’d ever lived in, and my family moved there following a trip through Southeast Asia—Singapore, Hong Kong, and Tokyo, followed by Vancouver. I was absorbed by the romance of big city life, and London had that in spades. The endless rain, the hyper-efficient transit system, the soot in your nose at the day’s end, the traffic, the noise, the urban sensations, it all seemed very familiar once I’d seen Ridley Scott’s classic. Maybe the British director’s vision for 2019 Los Angeles was inspired a little by London.

I know the themes of the film have been debated through the years; the biblical overtones, fallen angels, and the ambiguity around Deckard’s humanity, his disposition as a replicant, just like the androids he’s paid to track down and “retire.” Apparently Scott, the screenwriters, Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples, even the star, disagreed on this point. Despite the film existing in, count ’em, seven distinct versions through the years, this ambiguity is part of what makes Blade Runner great. My biggest concern with the arrival of a sequel so many years later—despite being helmed by one of the hottest directors in Hollywood, French Canadian Denis Villeneuve, and raved over in early reviews—is that the ambiguity will end. How can Deckard be a replicant if he grows old?

The things about Blade Runner I really loved weren’t to do with these philosophical arguments or plot details. For me, Blade Runner in any version is about mood, that exquisite alchemy of character, visuals, and especially music. I used to listen to the film’s soundtrack, by Greek electronic music composer Vangelis, as I was falling asleep. Now the music, and all that gorgeous imagery, lives in the corners of my dreams. Blade Runner is above all a world to visit.

Twenty-nineteen is almost upon us, and I still sort of expect it to look as it did imagined from the early 1980s. I expect the bars, the rainy, crowded streets, the flying cars, apartments inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House, buildings as beautifully ornate as the Bradbury. I doubled down on these visions of the future five years ago when I visited Los Angeles and a friendly local sharing my love of cinema was kind enough to give me a tour of BR locations.

Preparing for the new film, I watched the Blade Runner workprint version, available as part of the 2007 BR box set. It’s the only version of the five included in that set I hadn’t yet seen. It’s amazing, and maybe my new favourite iteration. It has the grittiest look, the sound cues and soundtrack are quite different—especially in the finale, which includes orchestral temp tracks, what I consider a more traditional Bernard Herrmann style, and there’s more interstitial scenes, more dialogue, though it’s still missing the Theatrical Cut’s campy voice-over.

The thing about this film that distinguishes it from most others: It can exist in these multiple editions with cults of fandom for all of them. I know folks who still love that original with the monotone Harrison Ford v/o. And I still discover fresh perspectives in these revisits to the various versions.

I love the smaller supporting roles: Joe Turkel—a favourite actor of Stanley Kubrick—as Tyrell, M. Emmet Walsh as Bryant, and Edward James Olmos as Gaff. The art direction, sets, costumes, it’s all continually spectacular. The effects don’t seem to age, even with all the signature 1980s visual elements—smoke, venetian blinds, and shoulderpads. The documentary about the film, Dangerous Days, reveals a largely unhappy, over-budget, torturous shoot, with Scott the never-satisfied perfectionist.

Recently I’ve considered that Deckard is actually the antagonist of the film, that Roy and his compatriots are the heroes. I’ve also come to terms with the film’s painful misogyny. Back in my undergrad, a fellow student tried to tell me as much, but I resisted. My flawed perspective was really based on my emotional reality around this thing I loved: I wouldn’t brook any argument that it could be hateful. These days I can’t deny the three female characters in the film, played by Daryl Hannah, Joanna Cassidy, and Sean Young, are all treated terribly. Two are shot and killed, and the other is treated to aggressive sex with very questionable consent. All this by the ostensible lead. It’s not something that gets talked about much, but it’s worth a conversation.

Now we’re here, days away from Blade Runner 2049.

As a rule I’m not a subscriber to the idea that a sequel three decades after the fact is a good idea—it’s next to impossible to capture the original electricity. Ask George and Steven about the fourth Indiana Jones if you need an example where it didn’t work. But I can’t deny this looks promising. A friend is reading Paul Sammon’s Future Noir, about the making of Blade Runner. In it he’s gleaned a clue to what the new film may bring—perhaps there’s something mutable about the replicants’ built-in obsolescence.

We’ll see.

Blade Runner 2049 opens October 6.