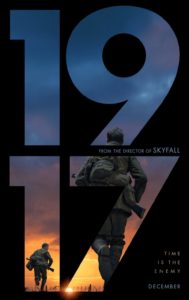

Directed by Sam Mendes | Written by Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns | 119 min

It’s April, 1917, and two British soldiers on the European front, Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay), are assigned to take a vital message to another battalion elsewhere along the line, orders to cancel a dawn push into a German trap. The stakes are simple and direct: the two men need to get from point A to point B, a distance of a few miles through the battlefield, and they have a limited time to get there. For Blake, the impetus is even more urgent as his brother is among the soldiers who will be going over the top the following morning.

This is Sam Mendes’ first feature since the two Bond movies, Skyfall and Spectre, and the first he’s had a hand in as a writer, based on his grandfather’s first-hand stories from the trenches. You can feel his personal investment as he brings all his considerable cinematic skills to bear.

In partnership with cinematographer Roger Deakins, Mendes directs a film that is almost one continuous shot, or at least a series of very long takes sewn together. This is some terrific use of CGI, almost invisible, exactly the way computer generated special effects should be used. Given the way the camera floats around the actors, swooping and swaying, the filmmakers must have applied a lot of planning and digital wizardry, with any wires and cranes removed in post production. It’s a remarkable achievement, with equally impressive work from the young stars providing solid character notes in what must have seemed as much a choreographed dance as an acting job, supported by veterans like Colin Firth, Mark Strong, Andrew Scott, and Benedict Cumberbatch. Mendes has watched a lot of films set in the First World War—1917 includes nods to All Quiet On The Western Front, Gallipoli, and Stanley Kubrick’s Paths Of Glory, with a scene where a singer holds soldiers in rapture with a song just as they’re about to return to the fight.

The question that lingers here is whether the formal means to the storytelling, the uninterrupted shot—as frequently breathtaking as it is—draws attention to itself to the disservice of the story. Is it just a gimmick?

I’m on the fence on this. For at least the first act, I caught myself marveling at what I was seeing, frequently wondering how they did it, which took me out of the movie. Or at least kept me at arms length. It’s not nearly as involving as, say, Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men, where the long takes exerted a terrifying, almost claustrophobic hold, and it doesn’t come close to conveying the brutality of the opening of Saving Private Ryan, where the opposite approach, jagged editing and sound design, delivered a feeling of chaos and terror that’s still hard to watch. Weirdly, the structure of 1917 also feels indebted to first-person-shooter video games and their immersive, point-of-view environments.

By the midway of the picture, I started to ignore the camera and give myself over to the story and Mendes’ cinematic confidence, such as when a character moves through ruins at night, an apocalyptic vision lit by the strobing glare of flares and a burning building in the distance, with Thomas Newman’s operatic score tying it all together. There’s a lot to enjoy in this film, single take or not.