I have been savoring American playwright Sarah Ruhl’s 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write this past month. Her quick, concise mini-essays have been helping me shape new ideas about theatre, and articulating some of my own beliefs in beautiful ways. Sometimes when I am engrossed in an author their cadence and language inhabit my head, and my thoughts are often in the ‘style’ of whomever I’m reading. So when I left the opening of Kim Parkhill’s A Good Death last night, the many questions that came with me were of a ‘Ruhlian’ fashion.

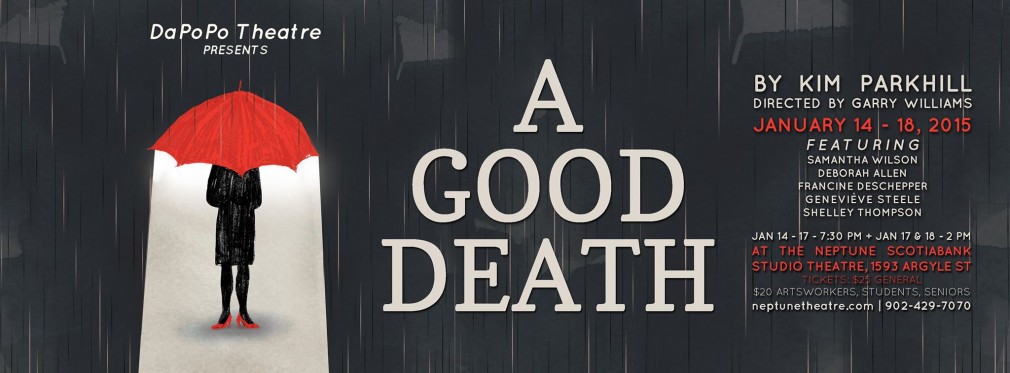

The play, produced by DaPoPo Theatre and Neptune’s Open Spaces program, and directed by Garry Williams, is meant to “examine the ethical, social, practical and emotional challenges” of a woman – called Woman – dying of cancer. Woman (Samantha Wilson) speaks directly to the audience and insists over and over again ‘this is supposed to be [HER] story.’ She wants to end her life before her illness takes away her ‘joie de vivre,’ “despite the obstacles.” The obstacles in this case are Woman’s nearest and dearest – Best Friend (Geneviève Steele), Lover (Francine Deschepper), Mother (Deb Allen), and Doctor (Shelley Thompson). Despite their presence, Woman believes the choice to die should be hers alone. But her loved ones don’t want to help her, even if she can promise them prison-immunity. The co-stars barely have a chance to present their own counter-arguments, as Woman’s direct audience address overpowers moments that feature the nuance of her relationships and the chops of the exciting five actors onstage.

Which leads me to my first Ruhlian question – When the playwright explores sensitive subject matter, just how sensitive must they be to their audience? Let me be clear before continuing — I am all for art that makes a person uncomfortable, and that illuminates ways of life that get the status-quo squirming. I also believe the topic of assisted suicide is worth hearty debate and discussion (and has explicitly shown up in my own writing). However my heart and brain were both left with a cavity at play’s end. I appreciate a piece of theatre with a strong ‘thesis,’ but what makes a persuasive argument different from a play are the people on stage connecting with one another, clashing with one another, depending on one another. A Good Death doesn’t argue that euthanasia should be legal, or that in certain cases it’s the best option — it argues that any choice other than assisted suicide is cruel and abnormal. Woman was so angry and forthright in her belief that she should be able to execute her own death, and her loved ones so tame, it seemed as though anyone who had passed away “naturally” from illness had been let down by their care-takers. This sounds like a harsh criticism but I found Woman’s relentlessness quite harsh in the first place. The lack of debate in A Good Death paired with Woman’s direct-address lectures to the audience felt quite overwhelming. The scenes where the supporting women get to interact are mostly token bits where each character represents a specific challenge of Woman’s decision and are quickly dismissed. Despite the bevy of incredible actors onstage there is little room for them to reach true human connection — their job instead seems to be embodying nameless persons standing in for walking, talking ideas.

In her twelfth essay Plays of Ideas, Ruhl separates “plays OF ideas” from “talking-ideas plays,” writing that “A talking-ideas play is different from a play where the idea is embedded in the form rather than in the conversation.” A play of ideas is moved by its topic, the protagonists’ struggles and relationships are propelled and transformed by dispute. The opinion of the playwright does not detract from the humanity of their characters. Ruhl is a champion of “feel[ing] something about characters because they too feel,” rather than “investing” in the facts of a character. I am advocating for this type of theatre, and feel disconnected when a play tells me what to think instead of demanding I exercise compassion. I crave humanity and heartbeat, not just intellect or cold isolating facts. I measure this longing against Ruhl’s insistence that writers keep from ‘sending their characters to reform school.’ She suggests one not focus on morality or the “completion” of their protagonist’s journey — there is no use asking “‘What did Godot learn from having waited?’” I get Ruhl’s point (though using an absurdist play seems a little leaning) — Sure, a lead character may not ‘learn’ anything and they don’t have to be “better” at the end. But if they are not emotionally moved in some way, if their guts don’t do a little quiver in response to the other people in their life, then I’m not going to quiver either.

All in all, it really is a bad-ass cast of women who I loved to see onstage together…though I take issue with another writer praising discussions of “duvets and cilantro” as groundbreaking womanly-conversation – but whatever. A Good Death is an exciting step for DaPoPo Theatre , and it’s pleasing to see the company receive grant funding, support from Neptune, and to branch out in terms of artists they employ. I have no clever exit for this post, so will once more turn to the fantastic Sarah Ruhl;

A Good Death plays until January 18

Neptune Scotiabank Studio Theatre, 1593 Argyle Street

7: 30 pm tonight- Saturday and 2 pm Sunday (Saturday matinee sold out)

Tickets: $25 general / $20 artsworkers, students, seniors

Available through Neptune Theatre Box Office in person & online

Sarah Ruhl’s book 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write: On Umbrellas and Sword Fights, Parades and Dogs, Fire Alarms, Children, and Theater was published in New York City: Faber & Faber, 2014.