The Georgian style of architecture is very common in early Halifax buildings. The style’s name is derived from the period it was most popular, during the reigns of Kings George I, George II, George III and George IV – roughly the period between 1720 and 1840.

The style, however, is also frequently mixed with Palladian influences. The Palladian style was actually a significant movement in England; however, it was also embraced by Thomas Jefferson in the United States, and combined with the Georgian style. Given many buildings in Halifax were copied from plan books from England, they could be considered to be purely Palladian. However, Halifax’s connection to the American Colonies certainly suggests some American influence. For our purposes, Georgian architecture includes Palladian.

Common identifying features of Georgian architecture include a 5-bay facade, massive chimneys at either end, and dormer windows in the attic. Also common is a central paneled door, and panel windows. Neo-classical pilasters and ornaments are also common to the Georgian style. Like Georgian, Palladian architecture features symmetry, and a neo-classical vocabulary. Buildings feel more massive at the base, and Palladian windows are common.

St Paul’s Church dates back to the founding of Halifax. It was one of the first permanent buildings to be laid down in the new city of Halifax, and it was given a prominent location on the main square in town. Due to the hill, the church is laid out with the entry to the north, and chancel to the south, in contrast to the normal practice of placing the entry at the west, and chancel in the east. (St Patrick’s and Saint Matthew’s follow this practice.)

The church, as it originally was built, is thought to have been copied from the 1728 “Book of Architecture” by James Gibbs, and is very close to Gibbs’ St Peter’s on Vere Street in London. There is correspondence from Cornwallis and Rev. William Tuttly, the Anglican minister of Halifax, which states “….it is exactly the model of Marybone Chapel”, and “…the plan is the same with that of Marybone”. Marybone is the original name for St Peter’s.

While the exterior matches St Peter’s, the interior differs from Gibbs’ style, and reflects more closely the work of Christopher Wren. It is thought that Christ Church in Boston is the model for the interior, as there are numerous similarities, and the timber frame for the church was constructed in Boston and shipped to Halifax. The reason for this difference may be simple economy. The small square piers of the simple Tuscan order are more easily and cheaply constructed than the more ornate round piers of Corinthian order that Gibbs preferred.

Originally constructed with 7 bays, the 8th and front most bay was constructed during the first major alteration of the church in 1812. This later addition added the entry vestibule, and moved the stairs to the upper galleries. The tower was also moved, and reconstructed over this new bay. The front porch also changed over time. Originally, it appeared to have reflected St Peter’s with 4 columns; however, it appeared to have been reduced to 2, placed in the corners when the extension was added.

The organ itself is the subject of an interesting story. The original seems to have been replaced between 1820 and 1841, however the original organ appears to have been destined for a Catholic church in Havana, Cuba, aboard a Spanish vessel. Britain and Spain were at war, and the Spanish ship was captured as a prize and brought to Halifax, where her cargo was sold. The church purchased the organ at that time.

St Paul’s was featured in the September 1912 issue of Electric World. St Paul’s was cited as “one of the most effectively lighted places of worship”. At the time, the church was already over 150 years old, and had recently installed electric tungsten lighting. The piece also makes note that “contrary to the impression that a dim religious light is a requisite for ecclesiastical efficiency, the cheerful illumination now enjoyed is unquestionably a decided factor in the attendance at this noted shrine”.

In 1917, St. Paul’s also was damaged by the Halifax Explosion. A relic of that day still pierces the wall, just above the main door.

The original engraving shows a Palladian influence, with the palladian window behind the alter. A palladian window can also be found on the front facade over the Grand Parade. The original entry was done in a neo-classical style, with columns supporting a pediment. The Georgian symmetry can still be seen on the building facade, giving it a highly ordered appearance.

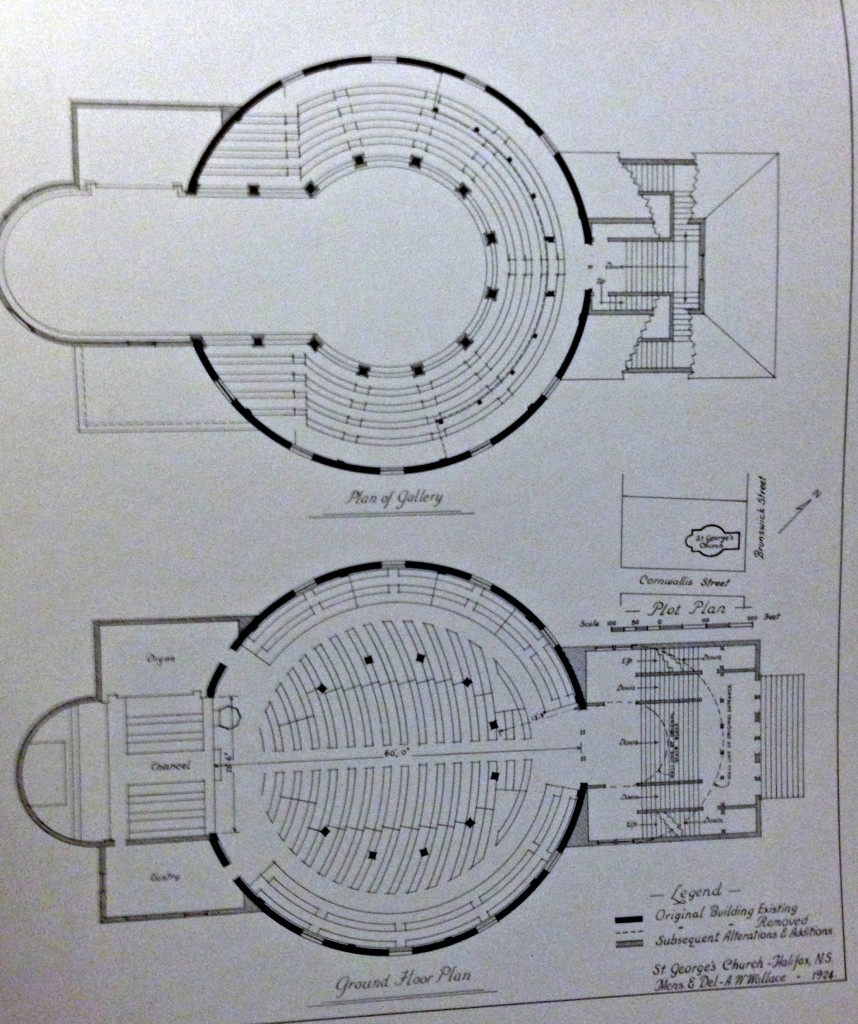

St George’s Church, also known as the Round Church, when built in 1800 was completely circular. This was the first round building in North America, though the type was well known in England. The design is credited to John Merrick, though it may have been copied from the 1728 “Book of Architecture” by James Gibbs, and it is from this source that St. Paul’s was copied.

In the plans below, you can see that the original entryway (denoted by the dashed lines) was also circular.

It is believed that the design selection was heavily influenced by Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent, who favoured round Palladian architectural styles. The roundness was based on the principles that the circle was the most perfect shape; and that by building a round church the devil could not hide in a corner.

Original round entry.

The square entry was added in 1911. The church was heavily damaged by fire in 1994, however it was rebuilt. A portion of the damaged round can be seen behind the main stairs to the left of the entryway.

(Above) Looking forward to the Altar from the balcony. (Below) Looking up at the dome.

(Below) The main aisle of the church. Congregation members would lease pew boxes for service, which is why they are divided and separate.

The Duke of Kent was also responsible for several other round buildings. The most well known is the Garrison Clock. The clock went into service in 1803, and the clock works were built by the royal clock makers at the house of Vulliamy in London.

The three tiers of the structure feature Palladian proportions. The base level features the Georgian 5-bay facade, with central entryway. It is thought that the upper portion of the clock is modeled after Bramante’s Tempietto, which was constructed in 1502 in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio, located in Rome. Palladio’s 1570 book Quattro Libri featured an illustration of the structure, ensuring it was well known by aficionados of his work.

Bramante’s Tempietto.

Another similar example is the Duke of Kent’s Music Room, the one surviving piece of his estate on the Bedford basin.

Built on the duke’s arrival in 1794, the influence of the Tempietto is obvious. In the Building the Duke of Kent also frequently entertained Governor Sir John Wentworth.

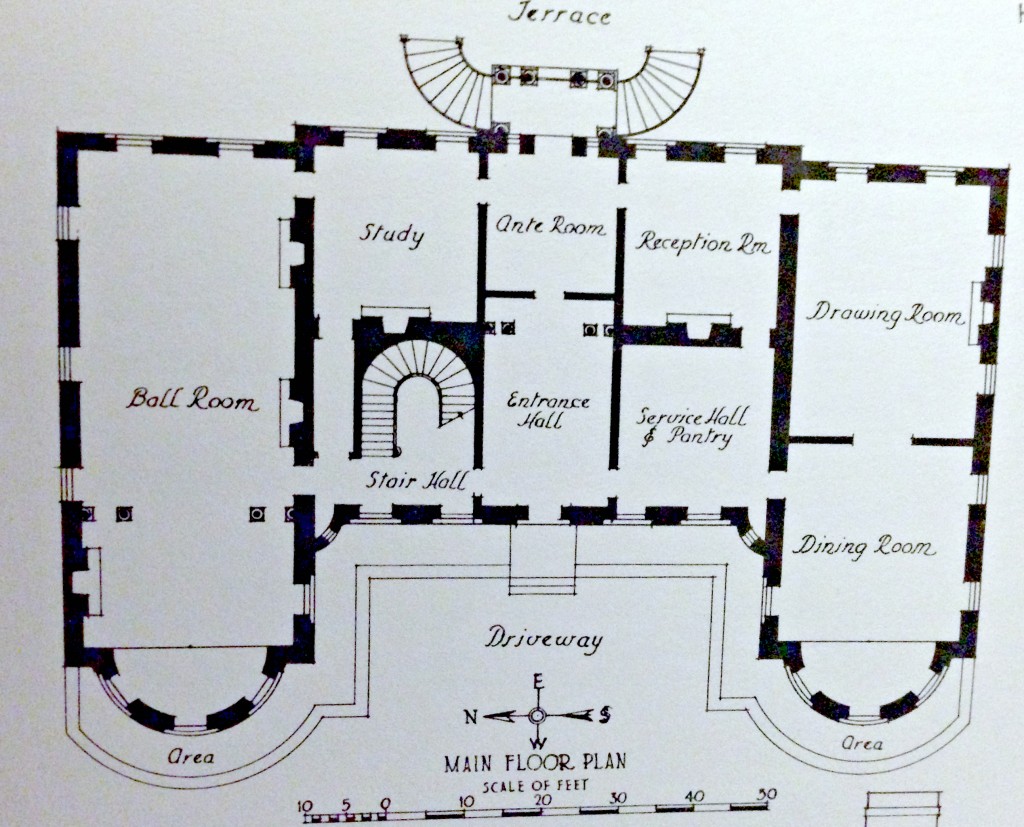

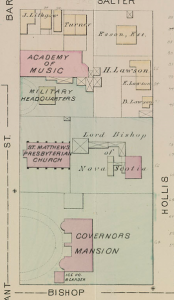

The third (and current) Government House was built by Governor Sir John Wentworth. Wentworth succeeded in convincing the Legislature that the second Government House was in poor condition and had been quickly built of poor materials. The Legislature agreed, and the current Government House began construction in 1800.

The house was designed by Isaac Hildreth, who served as both architect and builder, and is a Georgian style, based on plans published in 1795 by George Richardson, who published many books of plans which were widely read by architects. Architects at this time were typically apprenticed with people already practicing, or, in the case of Hildreth, master builders who would customize plans published by others.

Note the rusticated ground floor with the more finely-cut ashlar stone above. Also the Neoclassical details, such as the entry portico, and the doric pilasters. When Government House was built, the Hollis Street side was the principal entrance, however that duty is now assumed by the Barrington Street side.

Black Binney House, located next door on Hollis Street, is modeled after Government House. The house was built by merchant and legislative assembly member John Black, between 1815 and 1819.

The house features a 5-bay facade, massive chimneys at either end, dormer windows in the attic, a central paneled door, 6-panel dormer windows, and larger 12-panel windows, which are common identifying marks of the Georgian style and well displayed in the house. It’s also a pure representation of the style, with minimal Palladian influence.

Much like homes today, which use brick on the front, and much cheaper siding everywhere else, Black Binney House is faced with ashlar granite imported from Scotland, while the sides are made from the more readily-available local ironstone and sandstone.

Government House’s central portion features a similar 5-bay layout, and this is not surprising, considering it is next door. After Black, the house was lived in by James Uniacke, Premier from 1848-1854, then Hibbert Binney, Bishop of Nova Scotia. It became the headquarters for the Commissionaires in 1965.

Admiralty House served as the official residence of the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy’s North American Station. It was constructed between 1815 and 1819, and features the Georgian 5-bay layout, hipped roof with dormers, end chimneys, and 5-bay layout with central doorway.

More austere in its construction, the facade is made up of more roughly-cut local stone, as opposed to fine ashlar.

Province House is considered to be one of the finest Pallidian buildings in Canada. Started in 1811, and completed in 1819, it was designed by John Merrick and built by mason/master builder Richard Scott, who led the team of carpenters, masons and labourers who worked on Province House for eight years.

The facade is constructed of Nova Scotia sandstone, quarried in Wallace, NS. By placing the legislative chambers on the second floor, they have direct access at street level to Granville Street.

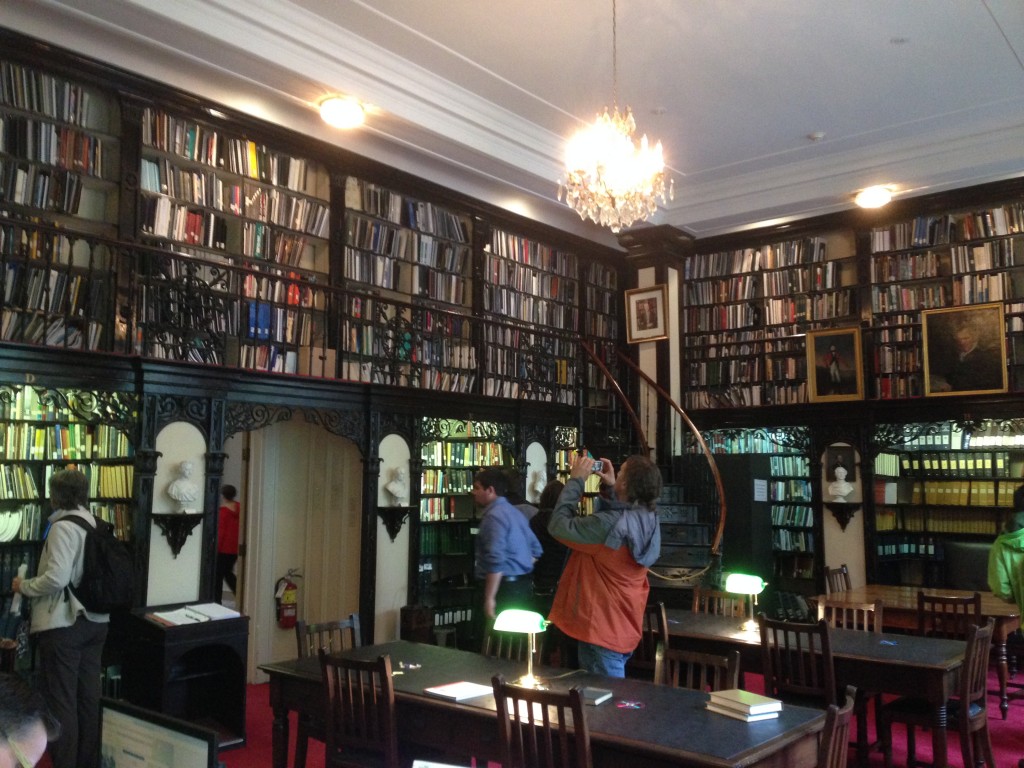

Legislative Council Room. This was the location of the Provincial Senate, when it existed.