Time to consider

We’ve been thinking a lot about time recently. The pandemic distorted our personal and collective experiences of time. We projected ourselves into the Good Future of a post-COVID world and dreaded the Wrong Future, where the endless cycles of plague and strife stretch on and on.

And yet, our growing concern with time and the future started before the pandemic. Did you make a habit of shaming the calendar year in 2016, or chastise the years afterwards for their increasing preposterousness and cruelty?

Time travel movie morals

We were hungry for media these last few years. Many of the most popular movies were about our fraught relationship with time. Avengers: Endgame and Terminator: Dark Fate fantasized that we could save ourselves from a Wrong Future. The virtue is hope. Recent time loop movies, like Palm Springs, updated the Groundhog Day motif for new generations, where our curse isn’t the banality of a good-paying, steady job but the fear of facing a future that is neither predictable nor wondrous. The virtue is responsibility. Tenet portrayed a present in direct confrontation with the future it creates, where we, here, now, are the mistakes to be corrected. We fight back because it’s in our interest, but the film can’t reconcile that we’re ultimately the villains. The virtue is conviction.

Do we absorb that the MacGuffins or technology that let the heroes defeat the Wrong Future aren’t options for us, virtuous or not? I often still feel the emotional catharsis of a near brush with the Wrong Future as though I’d learned something. None is more guilty of this than the new Chris Pratt vehicle The Tomorrow War, which despite being about time travel is not “about” much at all.

These days it takes forever for anything to happen, but we’re also a hair’s breadth away from “something else.” Social movements emerge, peak, get absorbed into the mainstream, and then disappear to the back burner in a matter of weeks. At the same time, we’re waiting for progress, for time to pass, like we’re stuck in our own time loop.

History and its cruelties keep slapping down our attempts to “move on” in the areas of social life that hurt our souls the most. Further, in the last 20 years, there’s been a growing pessimism, in North America and globally. Like never before, people seem to feel things went wrong, but there is no broad consensus on what went wrong and what needs to be done. There’s never any going back, but no going forward either.

“I started investing in Retro-Futures…”

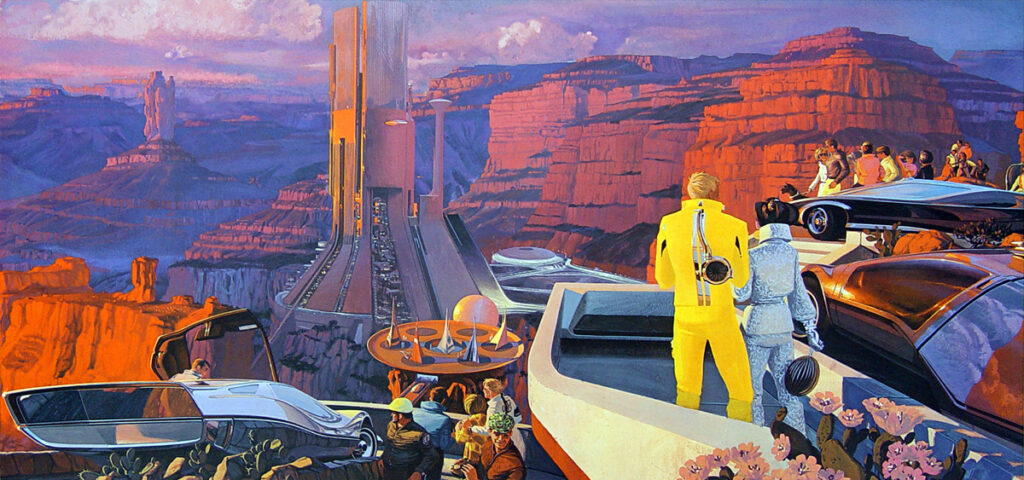

While we struggle to imagine our own Good Future, we find comfort and amusement in past attempts to predict the trajectory of history.

“Retro-Futurism” can mean a lot of things. Folks argue endlessly about whether it’s a genre, a sub-genre, style, approach, or philosophy. The term supposedly originated in 1984, in a review of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil by Pauline Kael, but you know it: “Yesterday’s tomorrows.” It’s your Jetsons, your Incredibles. It’s a 1986 book about cigarette cards from 1899 depicting Paris life in the year 2000.

Retro-futures are like that, tangles of old-futures, depending from whence you’re looking, looping back like ouroboros or a spirograph. They are increasingly commodified in our present. For instance, Synthwave music, Blood Machines and Altered Carbon simulate the “future of the 1980s” as understood by the late-2010s. The concept designer for Blade Runner, Syd Mead, said that he wanted to create a “retrofitted” future, messily strapped on a decaying past. Early-twentieth century pulp SF stories were based on the tropes of adventure tales of the late-nineteenth century, and so on.

Syd Mead

Retro-futures are numerous, and particularly helpful when studying the history of science and culture. With the benefit of historical distance, predictions vividly illustrate the dominant views about human nature and ingenuity, the priorities for society and leaders, the perceived direction of progress, as well as the unconscious biases that now glare in the light of the present. All these things point like an arrow towards a future that would never be.

In the introduction to the aforementioned Futuredays: A Nineteenth-Century Vision of the Year 2000 (1984), Isaac Asimov summarizes the history of “futurism” from the ancient world to the present, writing:

The desire to know our individual destinies has been linked, through the centuries, with our desire to foretell what will happen to humanity as a whole, to comprehend in all its complexity the grand sweep of history.

For Asimov, this history of humanity is the “history of progressive and everlasting series of technological changes.” By understanding the laws underlying these changes one might predict and direct this progress. His novel Foundation (1951) showcased the fictional science of “psychohistory,” which uses mathematics, sociology, and history to predict the future of humanity’s Galactic Empire in granular detail. It’s fairly obvious in hindsight that Asimov saw himself as Hari Seldon, the science’s genius inventor. But even Asimov became a product of retro-futurism.

“…because I knew it would happen.”

After claiming to have solved the problems of the “dark ages,” the scientific revolution culminated in claims of “causal determinism,” like those made by Pierre-Simon Laplace in A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities (1814). He proposed that if a being (“Laplace’s demon”) had the mental capacity to know the details and motions of everything in the cosmos then they could calculate its future states. “For such an intellect,” Laplace wrote, “nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eye.” By this star modernity charted its course for truth and power, and with it, techno-scientific and socio-political progress.

But Laplace’s demons, we are not. Retro-futures are often ridiculed by the present for being clumsy or cute. Their invisible biases are so humorously obvious to us while we swim like fish in our own turbulent waters.

Filming Tomorrow

One of my favourite pieces of retro-futurism is a 1957 episode of Disneyland called “Mars and Beyond.” It depicts the creation of the universe and the biochemical origins of life, as well as animates the history of astronomy and science fiction, all to prepare the viewer to understand how humans will travel to the planet Mars. (Bonus cameos by former Nazi rocket scientists). It shows how far they expected to go in a short period of time, but almost none of what was confidently predicted came to pass.

To be fair, our renewed interest in retro-futures is not because of their usefulness. Rather, we get high on their ambition and optimism. Director Brad Bird is a purveyor of retro-futurism in movies like The Iron Giant (1999).

His retro-futuristic, quasi-Randian Tomorrowland (2015) insists modern techno-scientific ambition still lies within a spirited, exceptional few. If society would only support those gifted individuals, hope for a Good Future could be rekindled. By the fruits of their labour they would bring back progress.

With shows like “Mars and Beyond” and attractions like the actual Tomorrowland, Disney had actively promoted futurism through a Jules Verne lens, which was already retro-futurism from almost a century before. Late-2010s audiences no longer identify with these projections of the old futures. They’re curios.

Promotional materials didn’t excite or attract viewers and the film didn’t impress critics either. For a movie about restoring the Good Future, it was vague about what the present problems were. But critics gave it credit for not being “disappointing in the usual way. It’s not another glib, phoned-in piece of franchise mediocrity, but rather a work of evident passion and conviction. What it isn’t is in any way convincing or enchanting.”

Again, perhaps the topic of the work is the author themselves. Not everyone is looking for an Art Deco future. For many people, depictions of futuristic worlds didn’t include them anyway. It’s easy to see why today’s culture wars can be reframed as the battle over who has control of the selection process for the Good Future.

Each group wants to stop their Wrong Future, but first….

The Allure of Retro-Presentism

… they fight to reset the Wrong Present.

Those 20th Century SF authors, like Asimov, who promoted “futurism,” were also practitioners of “retro-presentism.”

The problematic old guard, like John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and L. Ron Hubbard, each laboured to craft their grandiose personas as great intellectual men of the present—human embodiments of Laplace’s demon. As Alec Nevala-Lee outlines in his recent book Astounding, these men were obsessed with the heroism of the well-informed and ready-to-act Competent Man. This Man was the hero of their books and their dream selves. Their work paid off for a while, because through the fog of nostalgia, we still call their active years the Golden Age.

We know now that each man had character traits you wouldn’t see in their self-crafted personas or legacies, like Asimov’s relationship to sex and women, Campbell’s fascist leanings, Heinlein’s bullying and domineering, and Hubbard’s emergence as a cult leader and master manipulator.

These men taught many how to see the future. As time goes by, it’s easier to see how these darker elements impacted their visions of the future, who was in them, and who should run them. They advised that we avoid war by mastering psychology for social engineering, create sentient technologies that take our burdens away, re-educate those who cause social unrest, and build master weapons for the future threats that may face us.

We actively rewrite the past to reset the present and we always find something different when we look back, given our “fresh eyes.” Other times we ban the teaching of history and its impacts on the present because what it says offends our pride or threatens how we leverage cultural power.

It takes work to rehabilitate tropes with bad histories but lots of creators are retrofitting these problematic relics for new purposes. Every field has to constantly reckon with its past: What do we pull up front and what do we place further back on the shelf?

What do we care about in “the future”?

The Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition produced a book called Yesterday’s Tomorrows: Past Visions of the American Future (1984) with text by Joseph J. Corn and Brian Horrigan. Published two years before Asimov’s introduction to Futuredays, the authors seem to speak directly to Asimov in the future:

Insofar as the future has been identified in the twentieth century with technological advance, it has also been identified with consumerism – rather than improving relations between classes, nations, or races, or changing the distribution of wealth or standards of living – the future becomes strictly a matter of things, their inventions, improvement, and acquisition. (p. 11)

We seem to judge the Goodness of the future by how much more we have and how little the cost is. Our changing relationship to “the future” could be due, in part, to a shift in our relationship with consumerism, distribution of resources, and waste. When the “infinite potential of humanity” meets the finite resources of a finite Earth, a fragmented population, and powerful financial class, our various expectations will start narrowing too.

Future News

The “future” is never gone. Perhaps it’s quaint in 2021 to remark on the twenty-four-hour news cycle’s impact on social discourse and the shift from summarizing events past to commenting on events as they develop. We “geriatric millennials” are keenly aware of the blogification of news and how the once-belittled “online components” now wear the boss pants at media companies. (See Time Magazine’s 2011 piece “A Brief History of Digital News”.) Across all platforms, the structure is similar. What you need to know, why it matters, how to think about it, but mostly how it will impact the future. What about the next fiscal quarter, election cycle, franchise, the country, the soul of the planet, the souls of your close kin, who will come to get you, or take away what you have? How can you use this information to better yourself?

Social media presents all social and natural developments as potential news. So, while we wait for the future, we get the news behind that future news; the commentary and opinion about what will happen and whether it contributes to the Wrong Future. Strategy, speculation, past horrors, and the next crisis, are always loaded for bear.

Meanwhile, Bo Burnham asks: “Can anyone shut the fuck up about any single thing?”

My personal future

No. We can’t, but that “not shutting up” might be the only way the future really exists. The future, after all, doesn’t exist on its own. It needs a medium.

Personally, it’s been difficult to know how to write about these subjects. Exploring why I think we’ve stopped caring for the future is too great a topic for one essay and it will read to many like yet another rant from a smug pessimist. I also feel a pressure to reach for a hopeful or nihilist message to shield myself from criticisms of either taking it all too seriously or not seriously enough. Everyone will say you need to think soberly about the future, but it’s always the next sentence that throws us in different directions. What’s being left out? What’s the point? In a way, all these worries are also a means to mitigate the uncanny certainty that we’re heading for a “challenging future.” Like everything else, folks either know it already, reject it, or are tired of hearing about it.

Climate change presents one of the greatest mental obstacles between us and the future. As Ezra Kline said in an interview with science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson, the climate calculus and our legislative agendas do not show us stopping climate change. Stanley Robinson imagines that governments will act but not before millions of lives are lost and the cost of carrying on as is will be greater than the cost of changing.

Our technological and economic lives are so intertwined that any change is to be avoided because of its “impacts,” deferring the material and environmental costs to future others and future presents.

The pandemic showed our “retro-presentism” as an obstacle. Some thought the pandemic’s exaggerations of structural problems would lead to bold policy change, but instead we watched “essential workers” go back to being “essential functions.” What kind of future does that entail?

Leading us into the future

As we return to “normal,” it’s clear that “normality” itself is a retro-presentist myth.

Last year I wrote about how the heroes in science fiction movies taught us the wrong lessons to deal successfully with the pandemic. We are suffering from disillusionment with historical and living ‘heroes’ as well. Leaders across the board have often failed the pandemic test and worked hard to move the goalposts. And over time you could see them gradually losing the drive to “do well” and settle for “getting by,” and that’s in rich nations. Globally, pandemic and vaccine nationalism has taken the promise of techno-science and global cooperation central to old fashion futurism and used it for selfish ends, underlining to the rest of the world they really were expendable after all.

Those we hoped would lead us into the Good Future, and those many idolized for their moral examples, were revealed to be either too human, frauds, murderers, or sex pests.

Potential futures change when “patterns of expectation” change. In terms of domestic milestones, we geriatric millennials haven’t caught up to our parents’ retro-present, and the Zoomers (GenZ) are even worse off. You get less for rent, for labour and effort, but we still get a ruined system, climate, and environment, as well as increasing burdens of history, more hate crimes, and more hate generally.

We’re more aware that those expansionist aspirations, like space travel, now seem to resemble older colonial impulses more than contributions to the Good Future. The only necessary reason to go to space may be to escape a dying Earth.

Further, we keep hearing that trying to right past wrongs “divide us” but many are keenly aware that the divisions already exist. We have history books and lived experience. We are currently in a culture war about whether to protect a mythical past, and whether teaching that harm was (and is) done is harmful to the present. Some argue we should celebrate “moving beyond” the Wrong Past while also, somehow, celebrating it as the Virtuous Past.

For me, endorsing a mythical past just creates a mythical present, and that means the Good Future is just another myth. Why would we spend effort and resources on something we don’t believe will ever exist?

Bold futures

The return of history. The return of fascism. There’s a lot of shit news, growing in intensity: mass graves of Indigenous children and fresh graves compliments of anti-Muslim hate. The forests burn under heat domes and we watch flaming vortexes in the Gulf of Mexico, while sea creatures cook in their shells.

We prisoners of the present wonder why it’s still acceptable to use the tools of modernity to capitulate to those who actively seek to marginalize and eradicate groups of human beings, while treating the Earth like an infinite breadbox-junkyard.

Surely this is not needed in the Good Future, but yet here we are, stuck in our loop.

Science fiction movies often fail to provide satisfying answers to how we, here, now, can escape such loops of routine frustration and sublime trauma. The recent “Groundhog Day as an action movie” Boss Level offers the standard North American reaction: The past is designed to be left behind, even when you have the chance to do things over. Move on because the means to self-improvement are found only in action. But this lesson is only taught from habit, and the film doesn’t really buy its own bullshit. As usual, in movies, the fate of the world is the burden of the special individual, who in reality has little power to change the concrete systems that allow and encourage the mundane cruelty of the Wrong Present.

Ending with The X-Files

During a recent re-watch of The X-Files, I was struck by an episode called “Synchrony” (S04E19).

Scully and Mulder investigate the serial murder of scientists by an old man who seems to eerily know when events will occur. In the end, the old man is revealed to be a time traveler from an alternate timeline who “came back” to the present of 1997 to stop himself and his peers from creating a cryogenic compound required for the eventual development of time travel.

The future social psychological impact of time travel is catastrophic, and the old man pleads with his younger self to destroy his work or otherwise shepherd in:

“A world without history, without hope, where anyone can know anything that will ever happen.”

It strikes me as poetic that the most horrible of the Wrong Futures is the one that lets you know everything that will happen, effectively transforming humanity into a race of LaPlace’s demons. How tragic that the promise of scientific modernity would become a monkey’s paw wish, where there are only retro-futures. “Anything and everything all of the time” also happens to be how Bo Burnham recently described the root cause of our Internet-fueled malaise.

I’ll not pretend to understand what our current obsession with time and time travel ultimately means. I might say that time travel stories express a desire to escape the conditions of our imperfect lives and a chance to reset the present. I admire that the X-Files of 1997 called out that fantasy as naive bullshit twenty-four years ago. A look into retro-futurism sheds some light on what we hope to gain in the future and how those desires might not be that deep either. I’m starting to wonder if maybe the concept of the Good Future is itself a historical burden and whether caring for the present is the only real way to “invest in the future.” But I’m also wondering how long it will take before I look back on that statement, cringe at its clumsiness, and groan at how cute this all sounds.