Have you been bold enough to travel since the plague descended upon us? In September we made our first and only venture outside of Nova Scotia, to attend a wedding in New York State (congratulations, Hannah and Nick). An extra treat was visiting three special sites with similar themes: all are located on large tracts of land with striking landscapes, and each contained significant mid century buildings and art.

Manitoga

The industrial designer Russel Wright (1904-1976) was sort of in my consciousness, but until our friend Kathleen lent us a book about him I was not aware of his delightful home and studio. Wright is best known for creating a wildly popular line of tableware that brought modern design into the heart of North American households in the 1940s and 50s.

“Opened in May 2021, the Russel & Mary Wright Design Gallery tells the story of how the Wrights shaped modern American lifestyle.”

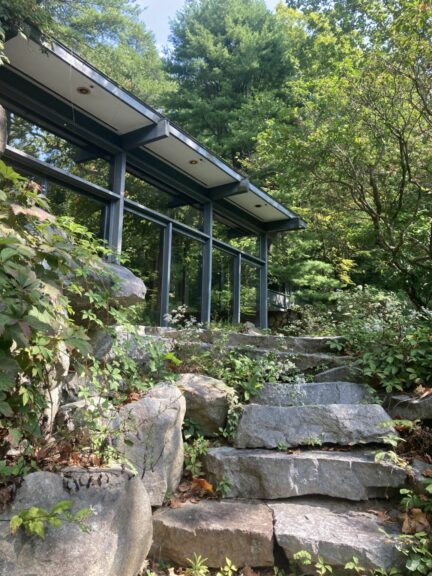

With his wife Mary Einstein (yes, she was related to Albert) he acquired the 70 acre property they named Manitoga (“place of great spirit” in Algonquin) in 1942. The site is near the Hudson River, about an hour north of New York City, and had been heavily logged and used as a stone quarry. The Wrights spent years learning to understand the property and making interventions to nurture the spirit of the place. In 1952 it was finally time to construct the house and studio their daughter named Dragon Rock.

Our guided tour approached the house site as Russel intended, viewing it from a distance perched on a rock face above a pond.

Japanese architecture was the inspiration for the building forms and the green roofs give them a contemporary feel.

It felt like it would be a good place to live, or at least stay for the month of September.

There is a serene sense of harmony between the built and the natural world.

The Glass House

While Manitoga was new to me I’ve always been aware of the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. It was built in 1948 and I would probably have started seeing pictures of Philip Johnson’s uncompromising glass box in the late 1950s. Johnson (1906 – 2005) played a pivotal role in bringing architectural modernism to North America and he had opinions about design that often invited controversy.

The Glass House was a wonderful place to visit but I wouldn’t want to live there. In fact Johnson himself was the only person to live there.

The interior has really never changed since it was built and I’d seen so many pictures it all felt quite familiar. In real life the space is larger than I imagined, and the herring bone pattern floor tile was more of a statement.

A 17th century painting of an imagined classical landscape is a clue to Johnson’s approach to taming his own 47 acre estate The painting is displayed on a stand because there are no conventional walls.

On the coffee table are a cigarette box and an ashtray, artifacts from another time.

Not a cozy bedroom, and super bright on a summer morning.

The bathroom is the only private space, concealed in a central brick cylinder that also houses the fireplace.

The big surprise was the Brick House built across a flat green lawn from the Glass House. Johnson considered that both buildings were part of a unified whole, with the Brick House offering services and guest bedrooms and other comfy spaces that the Glass House lacks.

The Brick House is self-consciously opaque and charmless from the outside. It was closed until some water issues are resolved.

Photo LANDTECH

Johnson designed his landscape to be picturesque rather than natural, similar to an eighteenth century British country house. Over the decades he kept adding structures that reflected his architectural ideas at that moment.

These garden follies include the Monument to Lincoln Kirstein (1985), a 30 foot tall concrete sculpture that Johnson designed to be climbed, but with some difficulty and a sense of danger. The Pavilion (1962) is a confection of concrete arches that extends into a man-made pond. It is scaled down to look distant when viewed from the Glass House and was a perfect location for Philip and his buddies to lounge and lunch on a summer afternoon.

The Studio (1980) was a library / study where Johnson could work away from distractions, like squirrels running past the Glass House. This little folly has no bathroom but is air conditioned.

A sculpture gallery (1970) has a glass roof that casts shadows that are almost too interesting. Imagine having the resources and inclination to build your own private sculpture gallery. There was also an underground art gallery with movable walls on the site. It was a good location for dinner parties.

To visit the Glass House you book a tour and meet at a visitor centre in New Canaan, Connecticut. From there the small group is taken for a 10 minute drive in a Mercedes bus along stonewall lined roads, past mansions of every colonial style imaginable. This is a very special and unfamiliar world.

Field Farm

So after visiting mid century houses for two days, on the third we got to stay in one. In Massachusetts an organization with the strange name Trustees of Reservation operates many sites to visit, mostly wilderness landscapes. One of their locations, Field Farm, is 300 acres of pasture, forest, and wet lands conveniently located on our route home in northwestern Massachusetts. We arrived to a sublime glimpse of Mount Greylock, the highest point in the state, and also a rainbow.

Our real reason for stopping was the Trustees operate an inn in the large 1949 house built by art collectors Lawrence and Eleanore Bloedel. The Bloedels wanted a modern house where all the rooms had good views, and provided appropriate settings to display their important collection of contemporary art.

The Bloedels wanted a delightful interior and were less interested in what the house looked like on the outside.

The exterior of the house is clad in very precisely fitted redwood. Lawrence’s family were owners of MacMillan Bloedel, the large west coast lumber company.

The art collection was willed to the Whitney Museum and the Art Gallery at nearby Williams College, where Lawrence was librarian. Paintings and sculpture from the collection are displayed in the house and guest rooms, and many of the original furnishings still remain.

The Bloedels constructed their own folly in 1966, a pinwheel-shaped guesthouse designed by a well respected modernist architect, Ulrich Franzen.

The shingle clad Folly feels very fresh and welcoming. The Bloedels enjoyed hosting skating parties on the nearby pond and serving hot chocolate in their welcoming pavilion.

We returned home very pleased with how our visiting experiences had turned out. If you want to know more about these sites there is lots of info online (there is an endless amount on the Glass House).

Postscript

- All of these sites have special programs to provide new perspectives and energy. At Manitoga while we were waiting for our tour there was time to visit a tea house designed by Yoshihiro Sergel and Diana Mangaser as part of an artist residency.

At Field Farm there was a temporary installation of giant terracotta figures by Rose B. Simpson. What perfect settings for both of these art works.

- One of the reasons to travel is to see things that do not exist at home. I tried to think of a Nova Scotian experience to match what we had seen in the US. The best I can offer is the Sobey Art Foundation collection displayed in Crombie House, the Pictou County home of Frank and Irene Sobey. The house has been closed during the pandemic but it is fun to visit, so keep checking their site.

The house has been added to and modified many times and is still used as guest quarters for significant corporate visitors. One write-up describes the Canadian art collection as “investment quality”, and it is instructive to see what was desirable in the middle of the last century when much of it was assembled.

Maybe a true story

In the mid 1970s the National Exhibit Centre in Pictou had a special showing of selections from Frank Sobey’s art collection, specifically 19th century paintings by Cornelius Krieghoff. Before the opening the director of the Centre offered a private viewing to the mayor of Pictou. After strolling around the gallery the mayor exclaimed, “this is amazing, I didn’t know that Frank could paint.”