Two weeks ago, Halifax launched its fifth new ferry. Residents of Halifax voted to name the ferry after Mi’kmaq poet Rita Joe, from Eskasoni First Nation in Cape Breton. Rita Joe is considered the poet laureate of the Mi’kmaq nation. The ferries are a popular part of the Halifax Transit network, running on two routes between Halifax and Dartmouth. The route to Downtown Dartmouth began running in 1752. Thousands of riders use the Halifax-Dartmouth ferries everyday. Clearly, our ferries have staying power.

Ferries have some big advantages over other transit vehicles. They cross water where there are no bridges, their biggest edge over buses and trains. Ferries don’t get stuck in traffic, and they can carry lots of people. The Halifax Transit ferries hold almost 400 passengers, over 4 times more than a jam-packed articulated bus.

Ferries also have some drawbacks. First, they are slow. Halifax Transit ferries top out at about 18 kilometres per hour. For short trips, low speeds are not a problem, but over long distances the travel time adds up. Long travel times are not appealing. Second, ferries are expensive to operate. They burn a lot of fuel and each boat needs a few crew members. Most buses and trains need one operator, and some trains and subways run without a driver, so having three or four operators per ferry is a significant expense. Third, wharves, ferry terminals and the boats themselves are expensive, and waterfront land is often scarce. Fourth, ferries don’t lend themselves to long, linear routes with many stops. Compared to buses or trains, they are also slow to dock and slow to unload passengers. Because every stop adds a lot of travel time, and maybe a detour, ferries usually go from one terminal to the other, back and forth.

The challenges inherent in operating ferries make them a specialty service. They work very well in certain situations. Because of the high operating costs, there needs to be a lot of passengers to make a ferry route worthwhile; lots of people per trip means lots of fares to offset expenses. But ferries are confined to waterways. Their terminals must be located on waterfronts, natural edges where roads and activities stop. Half of the catchment area of a ferry terminal is usually water, providing zero customers. The ferry terminal must have a dense catchment area to compensate, or be well located to capture folks travelling from farther afield.

Despite the challenges, ferry services operate in Vancouver, New York City, Boston, San Fransisco, and of course Halifax. Overseas there are urban ferry services in London, Hong Kong, Singapore and other cities. There’s a bit of a ferry boom happening. But, looking at a waterfront city like New York tells us much about the limitations of ferries.

The busiest ferry in New York runs an 8 km route, taking 25 minutes to travel from the northern tip of Staten Island to the southern tip of Manhattan. It’s a free service used by over 60,000 riders a day. This is a major operation, using 8 large boats and running every 15 minutes in rush hour. The ferry has a lot of features that make it useful and popular. The southern tip of Manhattan is an incredibly dense downtown office district, and the ferry terminal is close to a stop on the 1 subway line, which travels northward into Manhattan. On the Staten Island side, the terminal’s neighbourhood is the scale and density of a small city’s downtown. Also important, the bus network in Staten Island provides many routes that end at the terminal. A north-south rail line also ends at the terminal. The straightest line from most points on Staten Island to Manhattan runs through the ferry terminal. There are no tunnels from Manhattan to Staten Island, and the route by road crosses the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge to Brooklyn, a big detour, especially for people living north of the Bridge. This is a key point: ferries often succeed where they don’t have competition.

The Staten Island Ferry connects the northern tip of Staten Island to the southern end of Manhattan.

New York also has ferries running on the East River, which separates Brooklyn and Queens from Manhattan. In 2017, almost three million people used the East River ferries. That sounds like a lot of people, but the Staten Island Ferry carried almost twenty-four million passengers in the same year. Both numbers are big in absolute terms, but they are tiny compared to bus and subway ridership in New York. In 2017 the subway carried 1.7 billion riders, and the bus network carried 600 million riders. The problem, however, is not that the ferries move few people. It’s that the ferries are an expensive way to move few people.

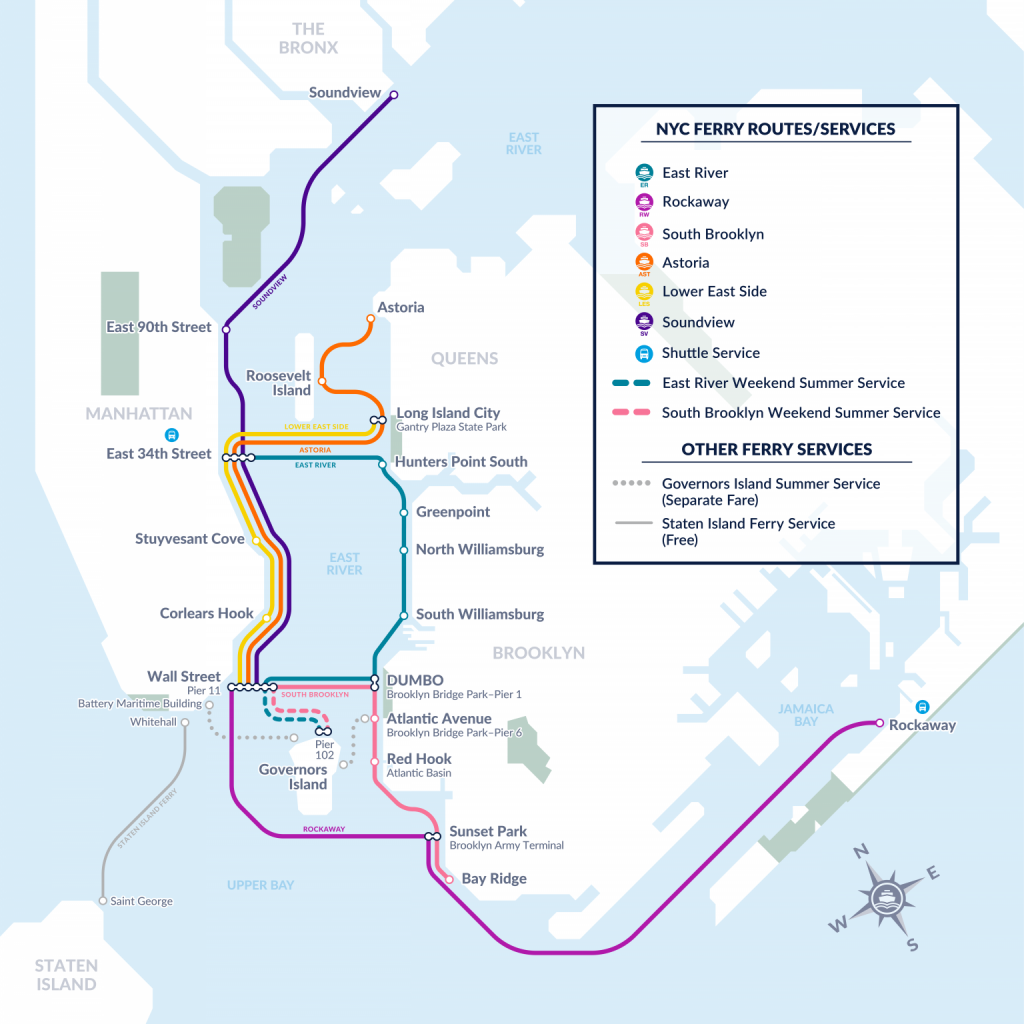

The East River ferries are particularly costly: $325 million to set up and $30 million dollars a year to operate. That’s a lot of money to move three million passengers per year! These ferries reveal the perils of urban ferry services. Using the water looks enticing – we’ll get out of traffic! We’ll connect big waterfront destinations. Wall Street is a big destination, and plenty of people live in Astoria, Williamsburg, DUMBO, the Lower East Side and Red Hook. But ferries are an especially poor way to travel when you’re running up and down the coast, instead of across a waterway. Each time the ferry docks takes lots of time, making the trip less appealing. Why spend almost 30 minutes on a ferry running from East 34th Street to Wall Street (yellow route above), if that ferry only runs every half hour? There’s a bus a few blocks away that’s as fast (or as slow, depending on your outlook). It runs every 3-5 minutes. There are simply better options than the ferries for trips within each borough.

There are also better options than the ferries for crossing the river. In 1883 the Brooklyn Bridge replaced an overburdened ferry service. More bridges and tunnels followed over the decades, providing new routes for cars, bikes and trains. New York’s subway is extensive and trains run every few minutes in rush hour. New York has lots of bus service, too. Because there are usually faster, more convenient options than the East River ferries, people choose the better options. New York has huge, unmet transit needs. Every dollar spent on slick, but inefficient ferries could do more good invested elsewhere in the system.

Ferries are a useful tool for urban transit systems, but they have limitations. They are slow and expensive to operate. Ferries are poorly suited to operating on long routes that connect many stops, the type of routes that make useful and efficient transit systems. Ferries offer good features, like freedom from traffic, that are a real need in congested cities. But on its own, freedom from traffic doesn’t overcome the downsides of ferries. Like any important choice, ferries involve trade offs. Too often, cities overlook the downsides and get caught up in the ease and joy of travelling by ferry. Marketing wins out over solid analysis. The good news is waterfront cities can always choose ferries for those special cases where they’re the best way to provide convenient, useful trips to lots of residents. The joy of sailing serenely to work or school becomes a bonus, and a great bonus at that.