I will start my post about Toronto with some qualifiers. I don’t know the city too well. The politics of transit in Toronto are pretty brutal, so where I can I’ll focus elsewhere – although it’s impossible to avoid the politics entirely. So if you know Toronto well and find my comments inane or uneducated, by all means pick a fight with me in the comments section. I’ll learn a lot. Plus, my blog can use the views.

I want to talk about Toronto because it’s a bigger network than I’ve ever written about, because it’s a high profile city, and because some issues are common to cities across the country. A few things strike me about Toronto transit: 1) overcrowding on the main lines; 2) tension between the suburbs and the inner city; 3) too much focus on transit vehicles; and 4) a lack of regional vision and big thinking.

The overcrowding, especially on the Yonge Subway Line, is intense. Rush-hour commuters pack the platforms and watch as train after train heads downtown, too full to pick up new riders. The most popular streetcar and bus routes are also crowded. Work is underway to upgrade signals on the Yonge Line, which will allow more trains per hour on the line. This extra capacity is needed now, but the problem will become more pressing when the Eglington Crosstown opens and delivers more riders onto the Yonge Line. There’s also a chance that any new capacity on the Yonge Line will be gobbled up by riders who have been avoiding it because of crowding. Meanwhile, Toronto’s population continues to grow, adding even more demand. A new subway line – the Downtown Relief Line – is planned to provide more north-south capacity into downtown, to relieve the Yonge Line. It is set to open in 2031. It will serve the central city with eight stations and cost billions of dollars. So far it is unfunded.

This is where transit planning in Toronto gets messy. The core network is already under strain. Population growth and projects like the Eglington Crosstown will make things worse on the Yonge Line, the busiest subway line in the city. The Relief Line is clearly a big need, sooner instead of later. But Toronto has other pressing transit needs, especially providing better transit in the suburbs. This is a classic dilemma for cities – invest in the existing, inner city system where there’s a high demand, or expand the system to under-served suburbs. Toronto has done a particularly bad job at having a reasonable debate on this issue.

Part of the problem is a misplaced focus on transit vehicles. In other words, the argument has been about whether to use light rail or subways, instead of how to build a good network for lots of travelers. This is not unique to Toronto, but Toronto has taken things to absurd levels. There is a sense – most clearly stated by the Ford brothers – that every area ‘deserves’ subways. If subways were cheap and quick to build, this would be no big problem; Toronto could finance and build several new subway lines and expansions all at once, providing lots of riders with better trips. But subways are hugely expensive, especially when they run underground through built-up areas. Toronto has committed to building a one station, multi-billion dollar subway expansion into Scarborough, instead of building a cheaper light rail option that would have provided more stations on the same corridor. Various options to reuse existing transit routes and right-of-ways were passed up, and instead the subway extension will run fully underground.

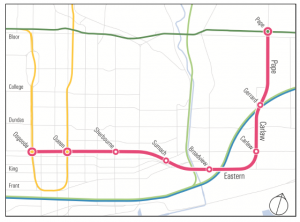

Proposed transit extensions in Scarborough, with the one-stop subway extension from Kennedy to Scarborough Centre shown in green.

The map above is from a Councillor drumming up support for the plan, but I think it makes some pretty strong arguments against the subway extension. The yellow line is another proposed addition to Scarborough’s rapid transit. This is a surface, light rail transit (LRT) line, running along Eglington Avenue. It has many more stops than the subway extension, for less money. But the province and city aren’t going to use LRT to get from Kennedy to Scarborough Town Centre, they are committed to a subway. Underground. Because the Scarborough subway will be so expensive, stops have been cut, reducing the subway’s usefulness. Without intermediate stops, the subway serve fewer neighbourhoods and will not connect to east-west bus routes on Lawrence Avenue. This is a common theme in Toronto’s transit network – missed connections between routes that almost meet.

This proposed subway line is an outrageous waste, which seems defensible only in some vague sense that subways are better. The intent of the extension is to convince voters in Scarborough that politicians care about them, not to solve actual transit needs. Meanwhile, pressing projects like adding buses and streetcars to reduce crowding, building light rail on Jane Street and starting the Relief Line get pushed down the priority list. Transit improvements to Scarborough – much needed – aren’t happening either. Instead, there’s been an argument over what type of train to use. Toronto just happened to pick the most expensive option, with the fewest stops.

Again, confusing technology with transportation options, or choosing political wins instead of serious governance is not a problem unique to Toronto. Let’s turn to something unique to Toronto. It has a network of streetcars. Unlike almost every other city in North America, Toronto kept its streetcars. This is an enormous asset. The streetcars connect dense, walkable areas of central Toronto. They run in nice straight lines. They have a smooth, comfortable ride. Most important, they are very long vehicles but still make tight turns (buses are hard to handle after a certain length). The newest streetcars in Toronto hold up to 250 people. Toronto needs this capacity on busy routes like Spadina, Queen, and King.

The streetcars also create challenges in a modern city. Traffic is heavy, and streetcars are tough to maneuver around even the smallest accident or blockage. Parts of the streetcar system have transit priority – reserved road space to allow transit vehicles to get out of traffic and move quickly and reliably – but it is a tough political fight to give transit more road space.

When the streetcar system was built, it served a much smaller city. Toronto has grown outward and is fortunate to have long avenues running the length of the city, both north-south and east-west. Strong grids are an excellent geometry for convenient and efficient transit networks. But the streetcar tracks only run part-way along most major avenues. Toronto has huge potential that its current street-level network isn’t taking advantage of, as transit consultant Jarrett Walker has pointed out.

St. Clair Avenue is a good example. The streetcar line stops less than two kilometers short of Jane Street, a critical north-south route, with one of the busiest bus routes in the city. There’s a gap in the network between a busy east-west route (St. Clair) and a busy north-south route (Jane). If St. Clair was a bus route, the solution would be simple – run the buses farther. But, this is a reminder that when a rail line ends, the service ends. Obvious, yes, but the consequences are big. Rail is tough to reroute and expensive to expand.

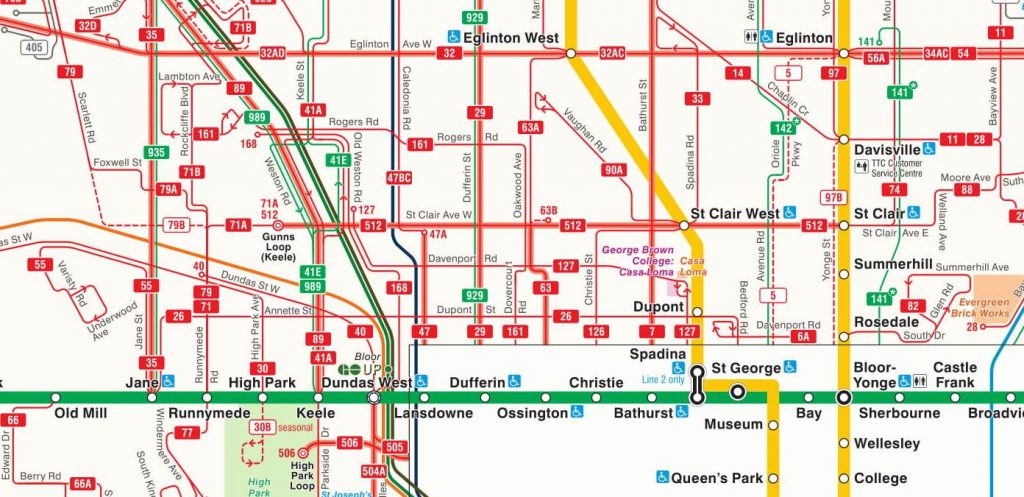

The St. Clair streetcar line (512) doesn’t extend far enough west to meet the busy Jane bus route (35). The gap in the network is about two kilometers long.

But in Toronto’s network, it’s not just streetcar lines coming up short. It’s common to find bus routes that end at subway stations, instead of continuing straight along the grid. This limits travel options. The 35 on Jane is one example – if it continued south of Bloor it could run down Windmere Avenue and connect with the 501 streetcar on Queen Street. Perhaps this would only serve a small percentage of passengers using the 35 Jane, but the neighbourhood around Windmere Avenue looks like a decent density for transit. Running the 35 Jane across the grid would be a small extension, but would fill in a network gap. Filling network gaps is a cost-effective way to provide more travel options and attract more riders. Small projects aren’t flashy, but help keep networks functioning well.

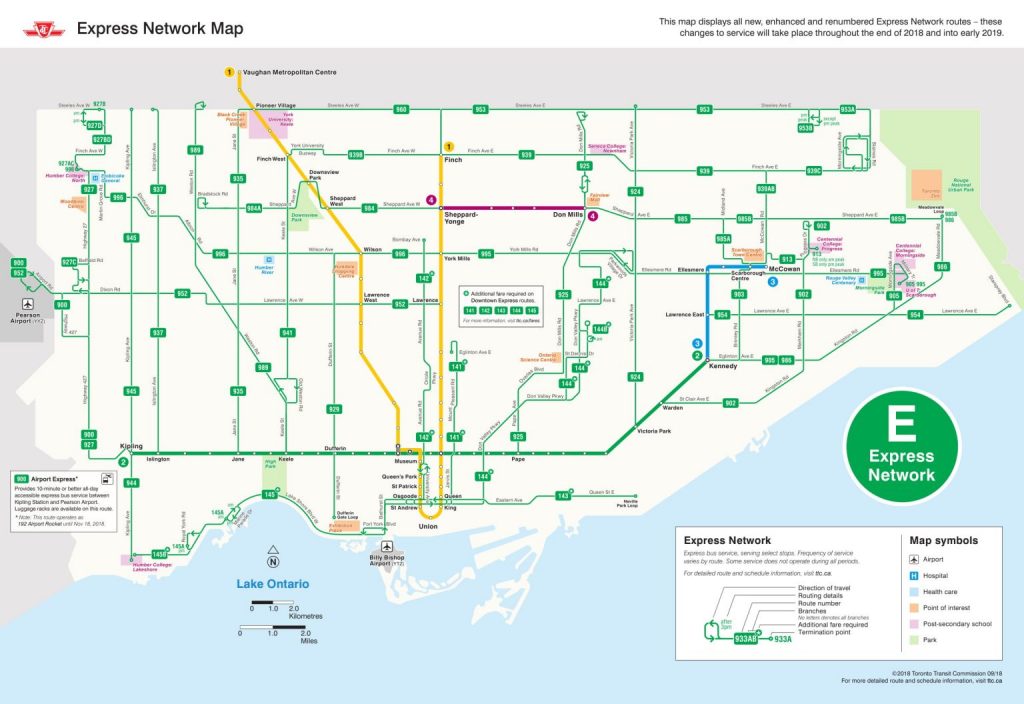

The gaps in the surface network also likely exacerbate crowding on the Yonge Subway Line. Consider the express network, below. These are enhanced or new routes, which offer fewer stops to increase travel speed. The 925 ends at Pape Station, funneling riders heading downtown from Don Mills Road onto the most crowded part of the subway system. Same issue for the 924 on Victoria Park Avenue. These bus routes are not be the busiest lines in Toronto, but both streets carry over 20,000 bus riders each day, hardly insignificant. Extending these routes southward, towards downtown, would provide connections to east-west streetcar lines, giving an alternative to the congested parts of the Bloor Line and the Yonge Line. More connections also mean more travel options.

The express network of the Toronto Transit Commission, which is launching in phases through 2018 and 2019.

Now, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) is scrambling to deal with congestion across the network, not just on the Yonge Line. Still, filling in the network provides more travel options and could provide potential relief to the worst congestion. It’s also faster to buy buses and streetcars to ease network overcrowding than it is to create new rapid transit lines (difficulties with current streetcar orders not withstanding).

The express routes seem part of a broader pattern, where Toronto uses buses primarily to shuttle people to the nearest subway station. With such a strong grid, and many four lane avenues, there is enormous opportunity to provide on-street rapid transit lines that extend across the city. Many on-street light rail lines have been proposed, including on Jane Street (still waiting), Shepperd Avenue East (planned) and Finch Avenue West (under construction). The Eglington Crosstown light rail line will also run on-street in suburban areas. Using existing right-of-ways, especially using existing streets, is cheap compared to tunneling or laying new grade separated rail lines. But, there have been massive political battles over on-street light rail lines, since they require space to be reserved for transit instead of general traffic. The battles continue.

Progressive mayoral candidate Jennifer Keesmaat had plenty of light rail lines in her platform, and I presume that meant reserved transit lanes. Keesmaat also included enhanced bus service on Steele, Victoria Park Avenue, Kipling and Lawrence West, although it’s unclear if the plan was for better bus service or high-quality bus rapid transit with reserved transit lanes. Regardless, surface rapid transit lines proposed for Toronto, whether by Keesmaat or others, often run part way across the city and terminate at the nearest subway station. In Keesmat’s proposal, enhanced bus service runs along Lawrence Avenue West and ends at Lawrence Station on the Yonge Subway Line. Extending the line three and a half kilometers eastward would connect this line to the Eglington Crosstown, via Bayview Avenue. On the way, the extended route would pass York University’s Glendale campus and two hospitals. Enhanced bus service on Keele Street ends at Finch Subway Station, instead of continuing north to finish the grid at Steeles Avenue.

The point is not to pick apart Keesmaat’s proposal, which is the most coherent political position Toronto has seen on transit in a decade. Rather, it’s to point out a subtle, unproductive bias about the role of on-street transit in Toronto’s network. Small missed connections add up to fewer travel options, especially for people trying to go across town to reach secondary destinations. Equally important, on-street transit need not be a secondary concern, since Toronto has more than enough transit needs and too little money to meet them all with subways or grade separated rail lines.

But back to the existing network. The biggest problems in the bus network are at the edges of the city. Few north-south TTC routes continue north of Steeles Avenue, the northern edge of the City of Toronto. Some of these routes run only in peak hours. Thornhill and Markham (in York Region, just north of Steeles Avenue ) look pretty similar to the suburban parts of Toronto just to the south. These are low density areas, which are tough to service. Perhaps a high level of service isn’t warranted or possible. That’s a judgement that has to be made. But the artificial break in the network creates needless hassles for people trying to travel around suburban areas. This may not be a huge percentage of riders, but there are suburban jobs in this area that must be difficult to access by transit. Toronto has a strong street grid that could support a more coherent network of local transit services. This would help people get to multiple destinations, not just the areas with high demand that are served by rapid transit. There are certainly big, pressing regional transit issues, but York Region and Toronto have an opportunity to cooperate and provide a more connected local network.

This is a small example of a bigger problem. The inability to think regionally. The Toronto area is Canada’s biggest conurbation (a cluster of towns and cities). Toronto is not just a big city with major suburbs that include Mississauga, Brampton and Vaughan. The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is now swallowing up old, standalone cities like Hamilton. The built up area known as the Golden Horseshoe spreads along the shore of Lake Ontario, almost continuously, for over 150 km, from Oshawa to St. Catherine’s and Niagara Falls (on to Buffalo if you hop the American border). Brantford, Cambridge, Kitchener-Waterloo and Guelph orbit this massive city-region. Somewhere between 7 and 9 million people live here, depending on which of the above cities and towns you count.

The lack of an integrated, regional rail network is a huge missing connection. The provincial agency Metrolinx is adding track and upgrading existing commuter lines to create frequent, all-day service across the GTA and parts of the Golden Horseshoe, in both directions. This project is called Regional Express Rail . It will cost many billions of dollars. Fare integration (one fare system across multiple transit agencies) is part of the project. This is a massive and important project, but of course there are squabbles over how Toronto’s vision (called Smarttrack) will integrate into the regional network. These squabbles seem manageable, and by Toronto standards minor, so let’s focus on the project itself. I couldn’t find a clear, up-to-date map of the proposed Regional Express Rail system from Metrolinx, so I used the lovely conceptual map below, found here.

First, the lines are radial, connecting central Toronto to the wider region. Given the number of jobs clustered in and around Downtown Toronto, this makes sense, but connections to other crosstown services will be key. Good connections will let more people travel across the region without heading all the way into Toronto to transfer. The Regional Express Rail system takes advantage of tracks that are, for the most part, already in place. This cuts costs, important in such an expansive system. Because the GTA and the Golden Horseshoe are so sprawling, a massive amount of transit is needed to service this area. Express Rail will provide many commuters with easier and faster trips across the region, especially people travelling to and from central Toronto. But even a big system like Regional Express Rail will cover only a small part of the region. This can be fixed over time, but certainly not cheaply or quickly. Linking local transit into the regional network is therefore critical. There are no lack of local transit projects underway in and around Toronto: a light rail line in Mississauga, bus rapid transit and light rail in Hamilton; light rail and bus rapid transit in Kitchener-Waterloo, Viva Next bus rapid transit in York; and of course extensions and new construction in Toronto itself.

The new transit proposals in the outlying cities look great. They will serve people travelling within the outlying cities and suburbs, and in most cases they connect to the subway network or the Regional Express Rail. The issues though, are in Toronto. In Toronto, on the TTC lines, is where the network is already strained beyond capacity. Transit planning in Toronto has been tumultuous since 2010, when Mayor Rob Ford started the process to cancel Transit City, an $ 8 billion plan to provide new rapid transit lines in the City. Toronto is where new riders from upgraded suburban lines are headed – onto a network which is under built and overcapacity. Toronto is where dense communities with high transit demand are left without rapid transit, while Premier Doug Ford muses about building underground subways to Pickering (15 kilometers farther east than the Scarborough subway extension). Doug Ford is also looking to take over the TTC, promising to get subways built faster. Who knows how this might turn out, but Ford’s priority is suburban subway expansions. Suburban expansions won’t create capacity to get downtown, but will add more riders to busy lines heading downtown. Creating more capacity in the City, where there is intense need, doesn’t seem to be a political priority. An extensive, but perhaps still insufficient regional network is slowly emerging, only to be made less useful by under-investment, chaotic decision making and poor prioritization in Toronto proper.

It might be good politics to pit suburban commuters versus downtown residents, especially since it hits directly at Toronto’s stark income and wealth inequalities. But it certainly isn’t good transit policy, since the network has to function as one entity. Besides, many commuters are heading downtown anyways. No one benefits from overcrowding, least of all commuters. But hey, if it wins votes … Toronto is now in the interesting position of having the small government conservatives gearing up to support pricey subway expansions, while the progressive leaders have often focused on more cost-effective light rail plans. It’s amusing: spend-thrift conservatives lined up against thrifty progressives.

It’s also worth looking at why they hold their positions. Rob and Doug Ford (conservatives) have consistently spoken for a few things: suburban voters and the little guy. From a suburban perspective, where autos dominate, reserving road space for transit is often seen as a war on the car, and by extension a war on the suburban way of life. Choosing to build more subways downtown is not meeting a pressing travel need, but pandering to wealthy residents living in expensive neighbourhoods. Progressives, like Jennifer Keesmaat, look at the downtown as the economic and cultural heart of the city, an area to be nurtured. Street space is seen as a public resource, which must be used wisely to support the needs of a diverse, growing metropolis. Transit debates quickly becomes a visceral proxy-war, standing in for deep disagreements about how to build the city and who the city belongs to.

I can sit back and look at Toronto’s transit woes with detachment. I can offer ideas to Toronto, but they aren’t much different than what’s been proposed and fought over a dozen times already. The deeper problem is that Toronto is a fast growing, global city. In forty years, Toronto has gone from Canada’s second city, to the unquestioned alpha. Toronto is swallowing its neighbours and becoming the heart of a massive, wealthy, inequitable city-region. It strikes me that Toronto’s temperament is almost adolescent: suddenly much bigger and stronger, but not really sure what that means or what to do about it. Until there is a collective sense of where Toronto is going, I doubt there will be a clearer debate around transit. Toronto has yet to figure out exactly what it has become, and how it wants to respond. Meanwhile, the city continues to grow. Perhaps Toronto will find some consensus before the transit system grinds to a halt.