Just before you reach the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick border on the Trans Canada Highway, close to the truck weigh station, you pass over the route of the Chignecto Ship Railway. This was a massive 1880s construction project designed to lift an oceangoing vessel out of the water and onto a rail car, hauled by two locomotives on parallel tracks. If it had been completed, the railway would have given ships a shortcut between the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It would also have been an engineering wonder.

When money ran out in 1891 many elements of the project had been completed, but construction stopped and the works were ultimately abandoned.

A recent newspaper story reported that piles of cut sandstone, assembled for the project, were being lost as the shoreline eroded, and the province was encouraged to step in (we own the site). This reminded me of the time I visited, in 1983, and here are photos of what we saw then.

Growing up in Nova Scotia I knew of the ship railway as yet another grand scheme that turned out poorly, but didn’t realize that much of it had actually been built. On the ground, with the help of some expert knowledge, my mind was changed. (You can easily find the full story of the railway online. UNB Archives has the major collections and great photos.)

Taking small roads back of the Nova Scotia Welcome Centre, we were soon crossing flat dykelands and arrived at the mouth of the Missaguash River, the Fundy terminus for the railway.

Here is some of what we saw. I think these were mounts for the engines that would lift vessels out of a massive, stone lined basin.

The base of a brick chimney (for a steam engine?).

This 1890 photo shows the basin excavated and walls under construction. The chimney and engine house we saw in ruins are in the middle. To the left are stockpiles of construction stone.

And here are similar piles of stone that we found. The landscape and the view down the Bay are striking.

Some of the stones were very large, perhaps the ones now sinking into the soft, and dissolving, shoreline.

Another sign of the project’s sudden death were these abandoned barrels of cement. The cement hardened and the wooden barrel staves rotted away.

Google Earth shows the state of the site. In the centre of this photo a large pile of rocks is sinking or sliding down the muddy bank. The basin (to the right) is now filled with mud and the traces of the engine house look precariously close to the edge.

Our little group were friends who had an interest in industrial archaeology, and occasionally we would visit sites. Mary Ellen Herbert, in blue, was our guide on this expedition. She had taught school in nearby Amherst and knew the stories and sites of the ship railway. She was also an early and enthusiastic promoter of more local history in schools.

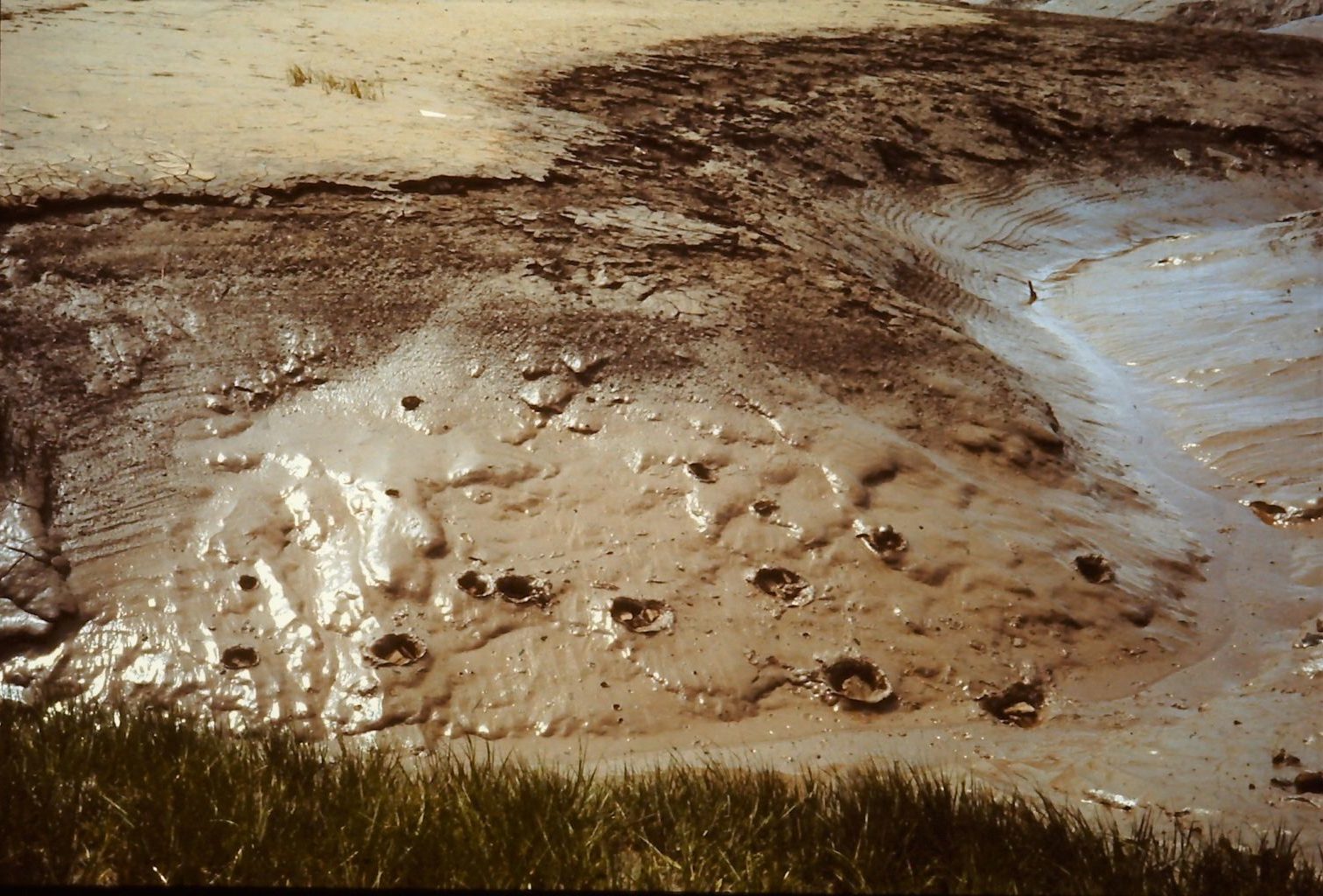

Before moving on, we took a moment to toss rocks into the soft mud. As one does.

If you look on Google Earth you can trace the 28 km roadbed of the railway, right across the isthmus. Close to the terminus at Tidnish is the best preserved element of the project, a robust stone culvert.

Here it is under construction. Many of the workers were apparently Italian, brought over for the project.

What now?

My first inclination was not to be too excited about a pile of sandstone sinking into the mud (we regularly knock down better than that in Halifax). But looking at these photographs reminded me of the power and strangeness of that landscape. The stone is a foreign element and provides a different dimension. So today I vote to move the stone away from the shore. How much can that cost? And use it as an excuse to get people thinking about the rising sea levels that will soon make Nova Scotia into an island.

Postscript

- We stayed overnight in Borden’s Motel in Sackville. In 1983 it could already be appreciated as deliciously retro.

The next day Mary Ellen took us to see remnants of a hugely successful, 19th century industry: grindstone quarrying.

Just down the shore from the fossil cliffs of Joggins are reefs of sandstone, especially suited for use as grindstones. Throughout the 19th century blocks of stone were quarried at low tide, and lashed to boats that would then be lifted by the Fundy tides. The stones were floated to shore for finishing.

Some large grindstone blanks could still be seen on the beach, abandoned when a flaw was discovered in the stone.

The owner of this operation was Amos Seaman (1788-1864), the Grindstone King. We saw the foundations of his once grand house, on the edge of his immense dykeland, called the Elysian Fields. This landscape is another treasure that I suspect few people outside the area know about.

Here is King Seaman’s Georgian style house in 1875. Better times. That’s the corner of the foundation we saw.