Does this weather get you thinking about sunnier places and warmer times? I’ve been remembering a big summer house we visited regularly in the 1990s, that relaxed comfortably in a mature landscape on the Atlantic coast near Chester, Nova Scotia.

Our friend Joanne was a friend of the owner’s family, and would rent the house for a month and then let rooms to 8 or 10 friends. Sheila and I would stay a week or so.

Here I am playing a winning game of croquet in 1993, but usually eating was the only organized activity.

The star of this story is the house. It was fun to observe when people entered for the first time and realized they were somewhere very special, an intact survivor from another time. A ritual that many guests would perform involved trying to reconstruct the history of the house and why it felt so beautifully perfect.

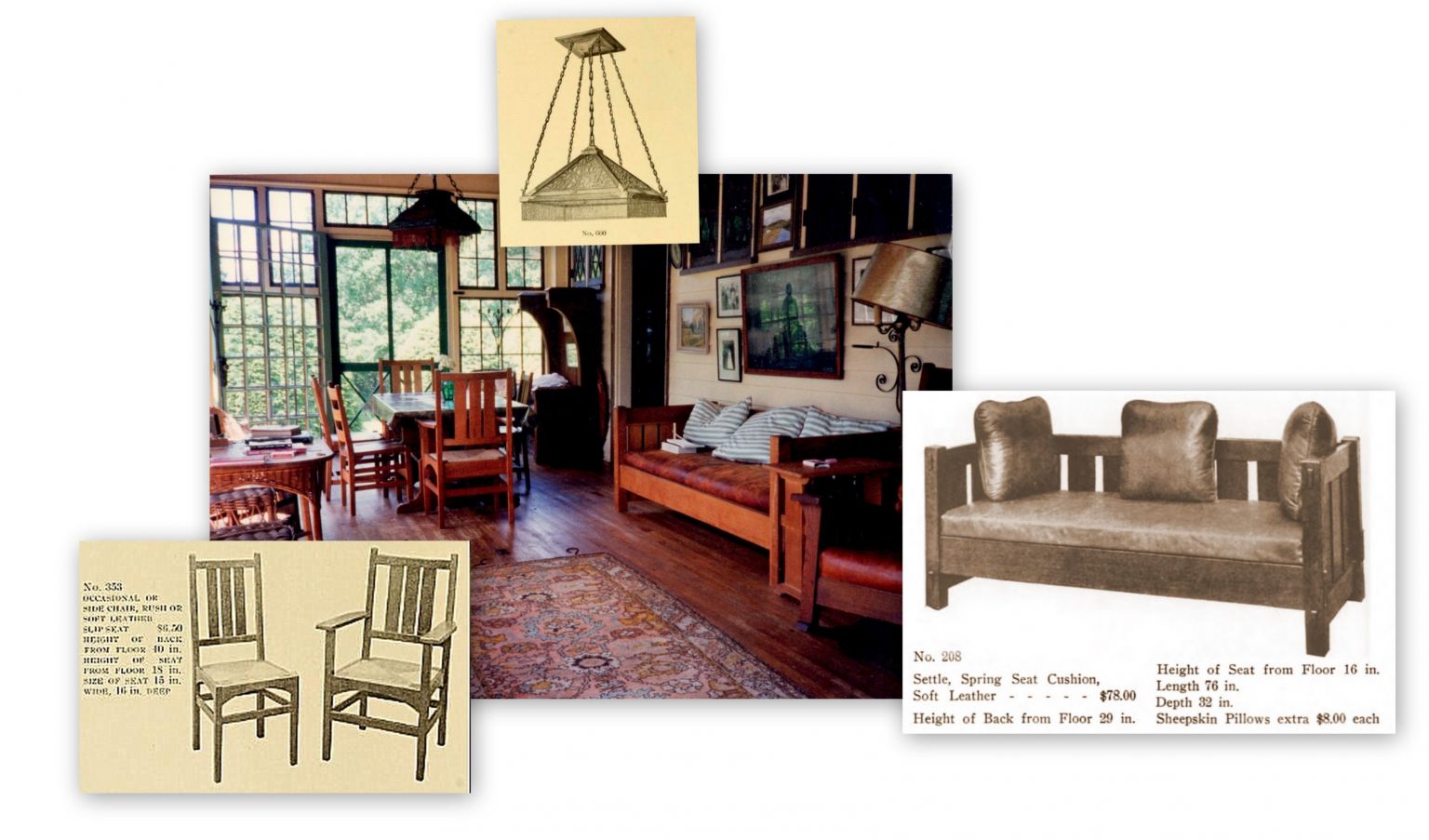

My version of the creation legend is that the house was built by a wealthy lady from Baltimore who was a cousin of Nathaniel Hawthorne (or was it James Fenimore Cooper). The woodwork was prefabricated in the states and shipped up here in the first years of the 20th century, and all the original furnishings were bought from the Gustave Stickley furniture company. During WWII, the house was used by Norwegian naval officers who had been at sea when their country was occupied.

Houses similar to this were built in places like coastal Maine and the Adirondacks by people wanting to escape the summer heat and unhealthy air of the big American industrial cities. It was designed for informal living, and we were probably using it as the original occupants intended. When new, the craftsman-style house would have felt very modern, a rejection of the fussy, over the top decoration of the Victorian period.

A defining feature of the house were generous sun porches that wrapped around three sides. On the east and west these were really long galleries, with floor to ceiling windows and hardwood floors, and big screened doors for cross ventilation.

At the water end of the west porch was a separate, fully screened room where you could sit or dine when mosquitoes appeared, as they do.

And facing the cove the porch was open. These spaces were so large that folks could spread out, reading or socializing in whatever light or view or breeze they desired.

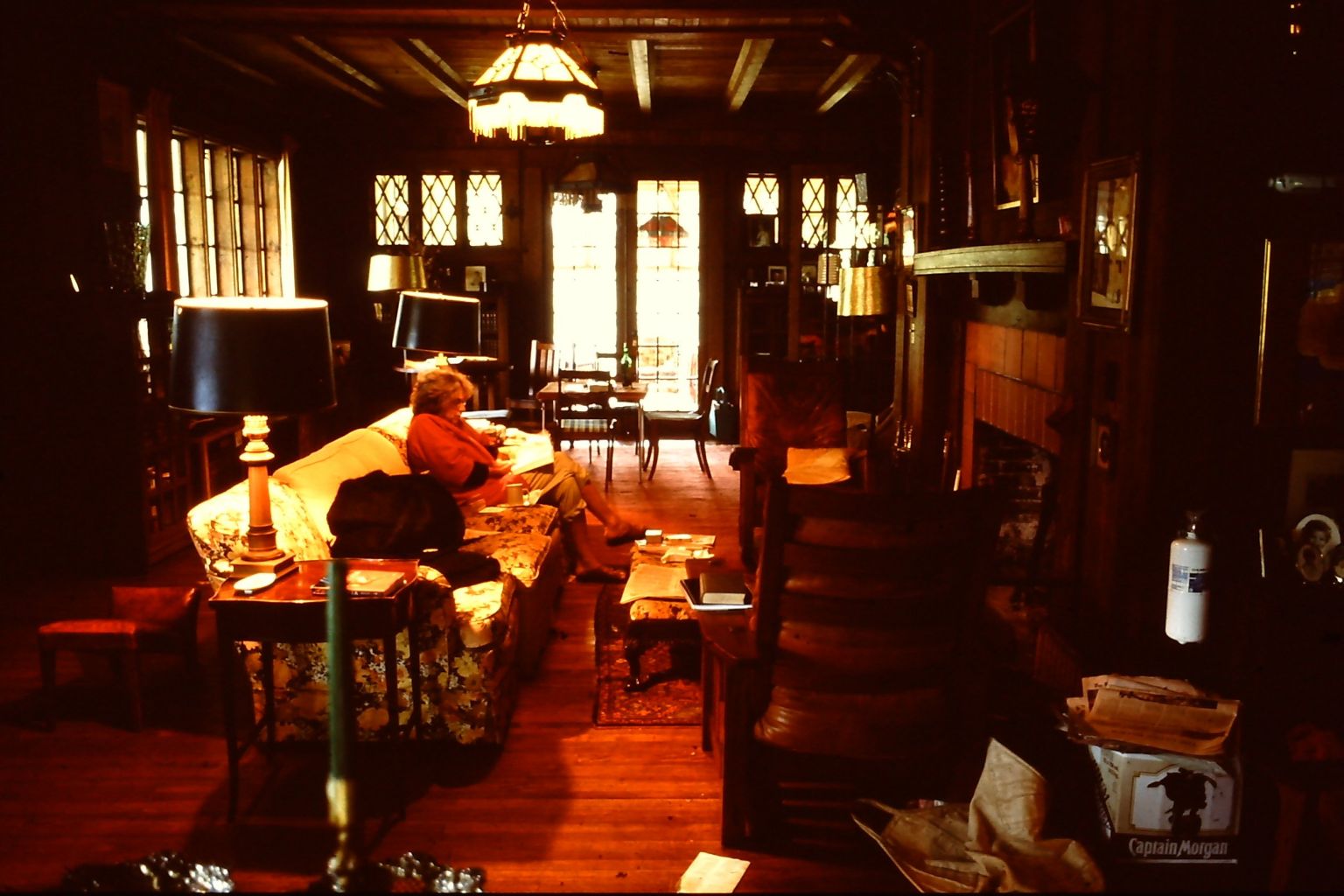

The core of the house was a living room that stretched the full width. The porches protected it from the summer sun and the room could be a shadowy haven on a scorching day or a cheery cocoon on cool nights around the big fireplace. The long narrow space allowed for an aggressive scrabble game at one end, letter writing at the other and drinks and storytelling by the fire.

Usually couples took turns preparing an evening meal, and the dining room table could accommodate 12 or 14 people.

Here some friends proudly display a meal they have prepared for alfresco dining.

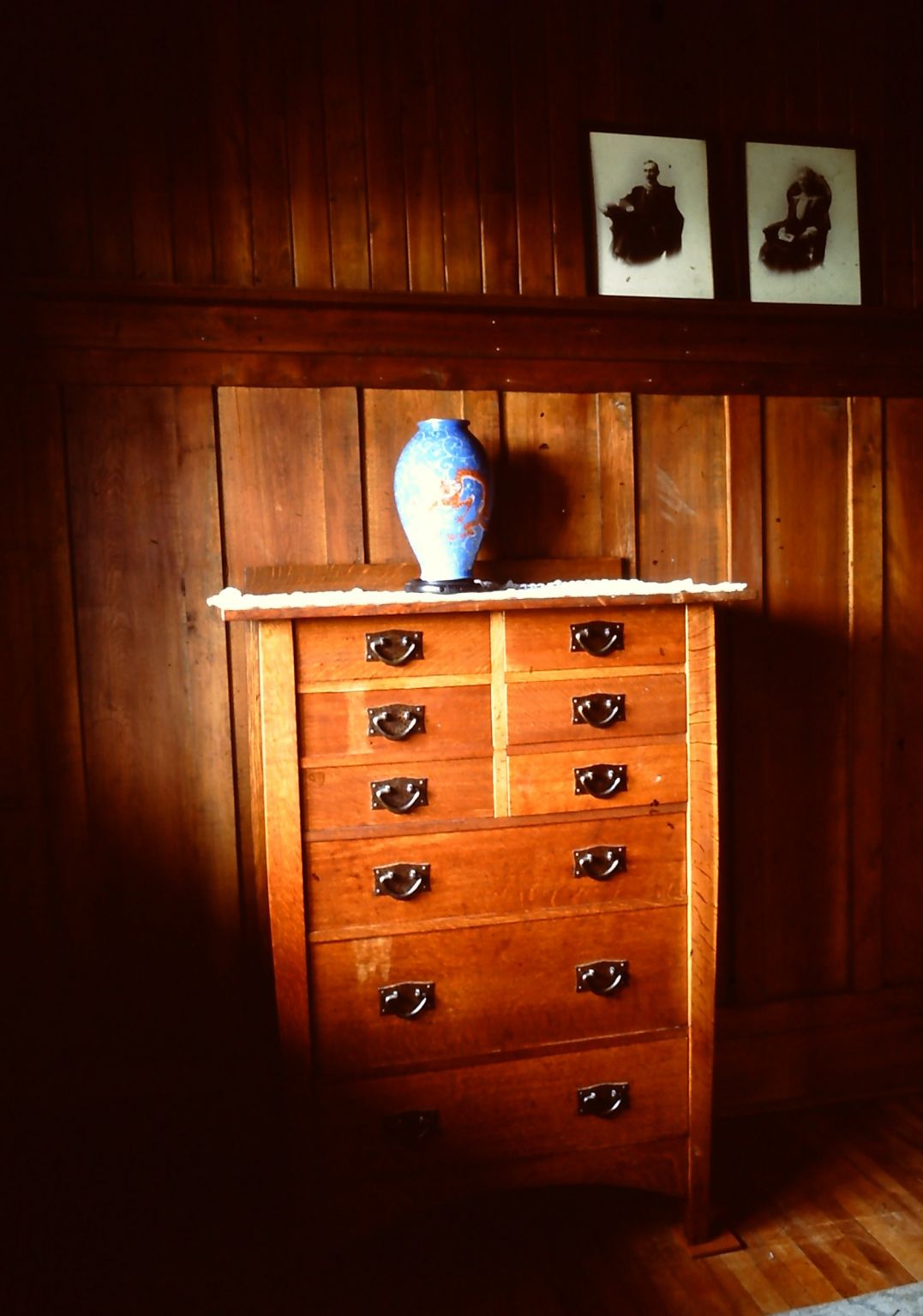

I forget how many bedrooms there were upstairs, but we were well accommodated in large airy rooms totally furnished with Stickley furniture. All the walls in the house were made of stained wood and the bedrooms had plate rails, ideal for displaying framed ancestors or beach finds. The wooden walls were perfect for a house that was empty and unheated in the winter and had only mellowed with age.

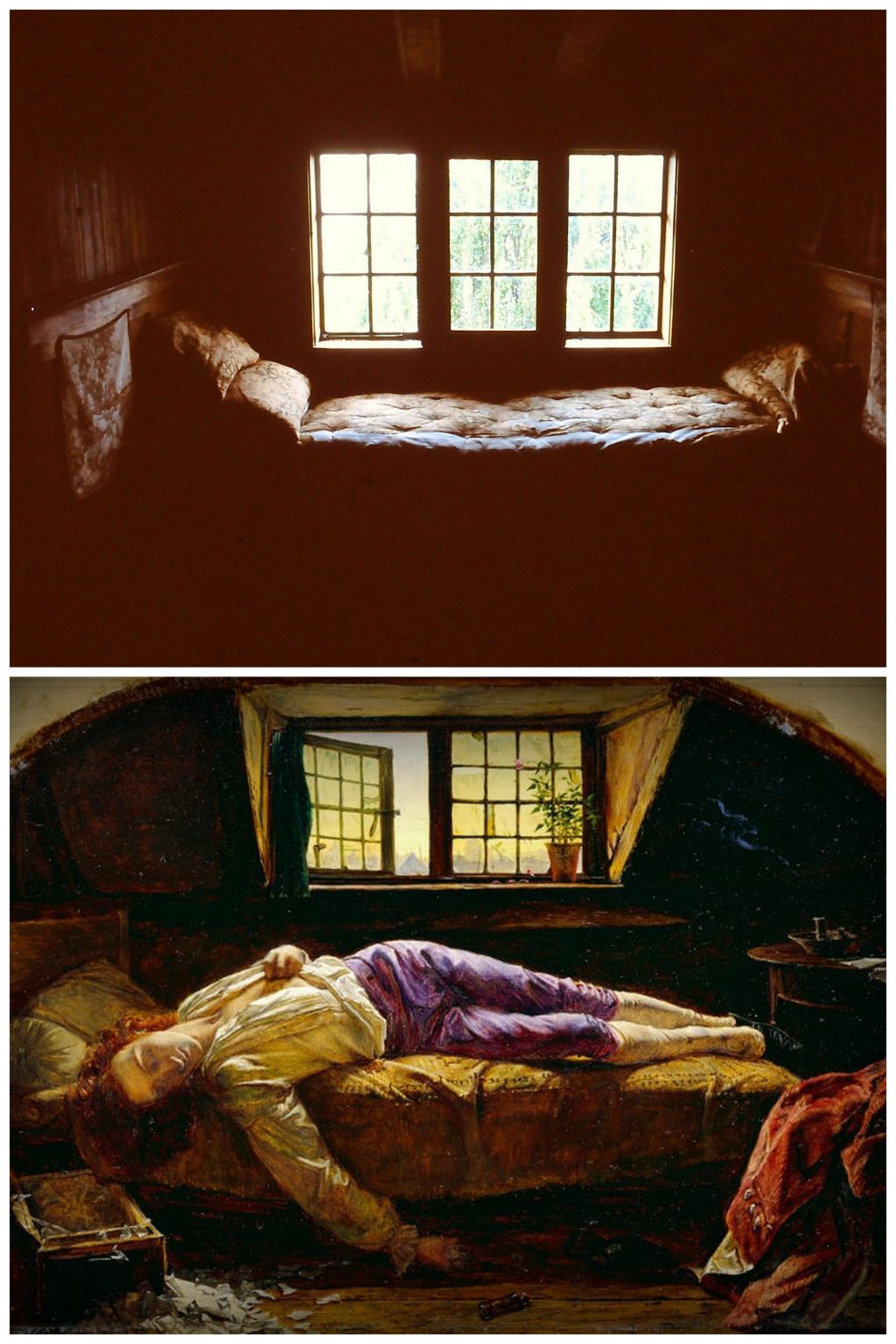

A classic summerhouse feature was the attic dormitory that you could imagine full of kids from school, invited to visit over the summer holidays. Lots of built-in cupboards, and window seats that could sleep more.

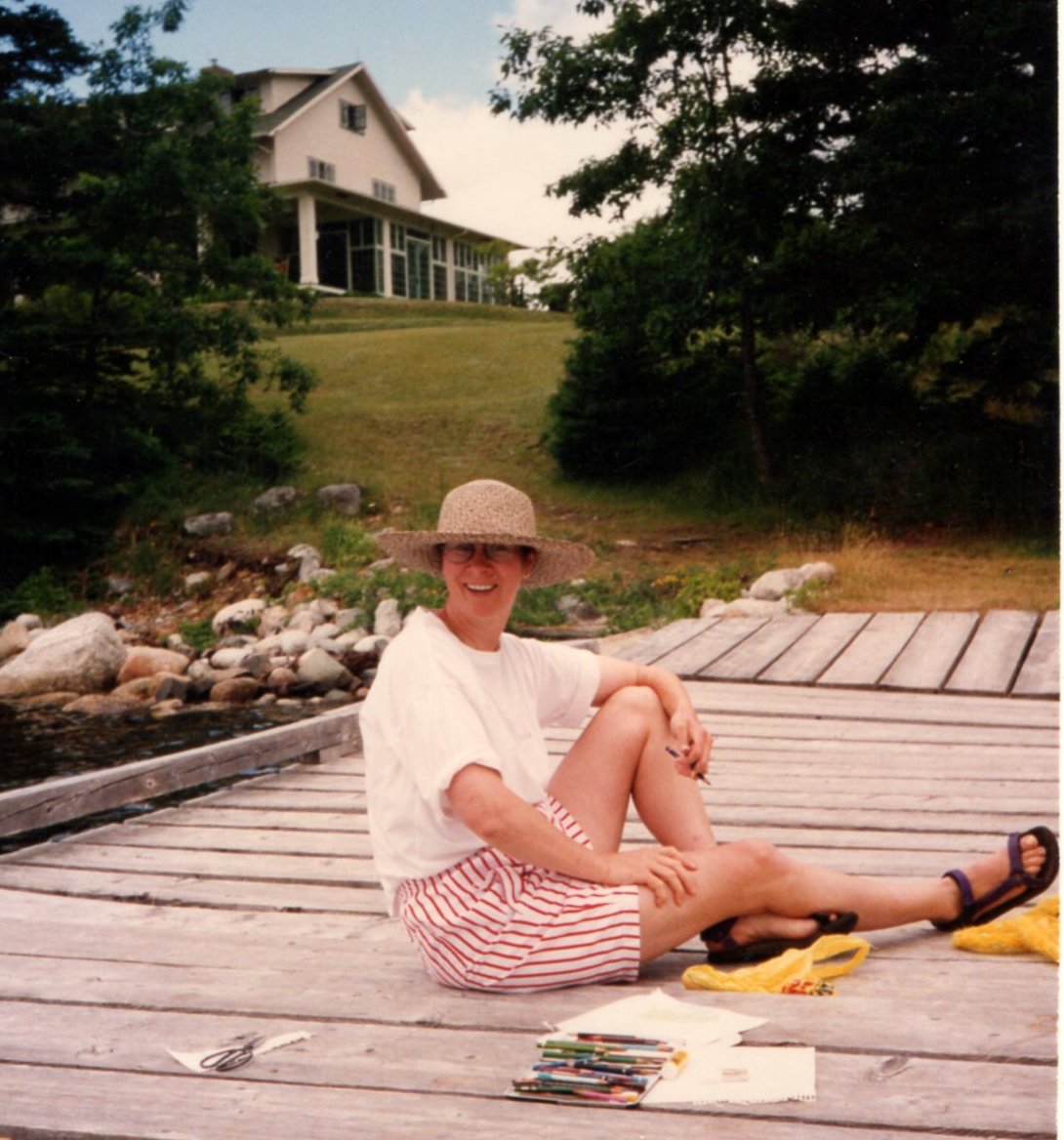

Just below the house was a sagging wharf projecting into the sublime cove.

Here Sheila and I have ventured down to the wharf to lounge in the sun and play with coloured pencils. In this time before WiFi and mobile phones, how did we manage to fill the time?

It was a privilege to have experienced this house, and to get a glimpse into an aesthetic world I didn’t realize existed in Nova Scotia. When the house sold around 2000, my understanding is that most of the original furnishings were auctioned.

Postscript

- Many Gustave Stickley furniture catalogs have been reprinted, and it is possible to leaf through them and identify most of the furniture in the house, including light fixtures.

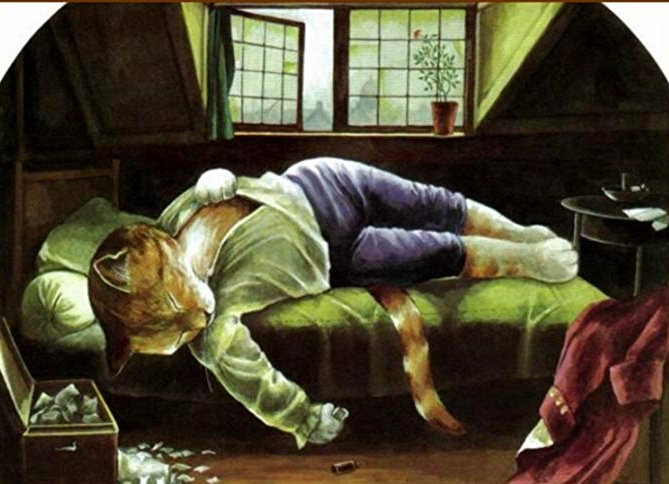

- The house was filled with positive energy so this allusion does not reflect on the character of the house. But, the window seats/beds in the attic windows immediately brought to mind “The Death of Chatterton”, a famous 1856 painting by Henry Wallis, that hangs in the Tate. See what I mean? Thomas Chatterton was a 17-year-old romantic poet who poisoned himself with arsenic in 1770.

There are also death of Chatterton cat memes. But that’s a different story. I’m sorry I brought it up.