A couple stories in the news recently got me thinking. First there has been lots of talk about the fire service and how many staffed stations it takes to keep our old people safe. At the same time there has been attention given to developers’ projects that propose to destroy whole blocks of existing buildings. In the 19th century those two stories combined: large downtown fires (sometimes blamed on an unreliable volunteer fire service) devastated complete streetscapes which were then rebuilt on a grander scale.

The most well known of our fires happened in September 1859 when the north block of Granville and surrounding streets burned. Big enough to catch the attention of the Illustrated London News who printed a fanciful engraving of the evening.

The accompanying story reported that “sixty of the finest buildings in Halifax, covering four acres of ground, were destroyed.” This was the premier shopping district (“the Haligonian’s paradise” said the London weekly).

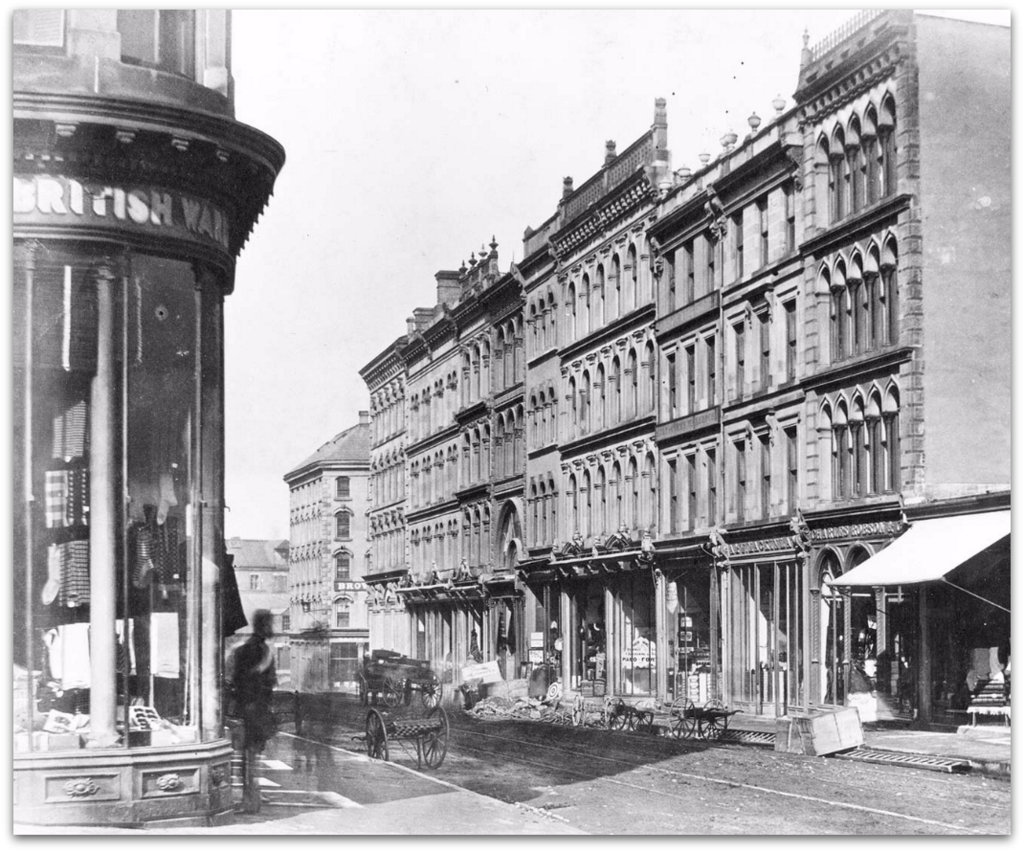

Granville Street was quickly rebuilt after the fire in a grander style than before. Here is how the east side of the block looked in 1871, about 10 years after construction. These are the buildings that NSCAD owns and occupies.

The quality of the rebuild makes the streetscape the best example of commercial architecture of this time in Canada.

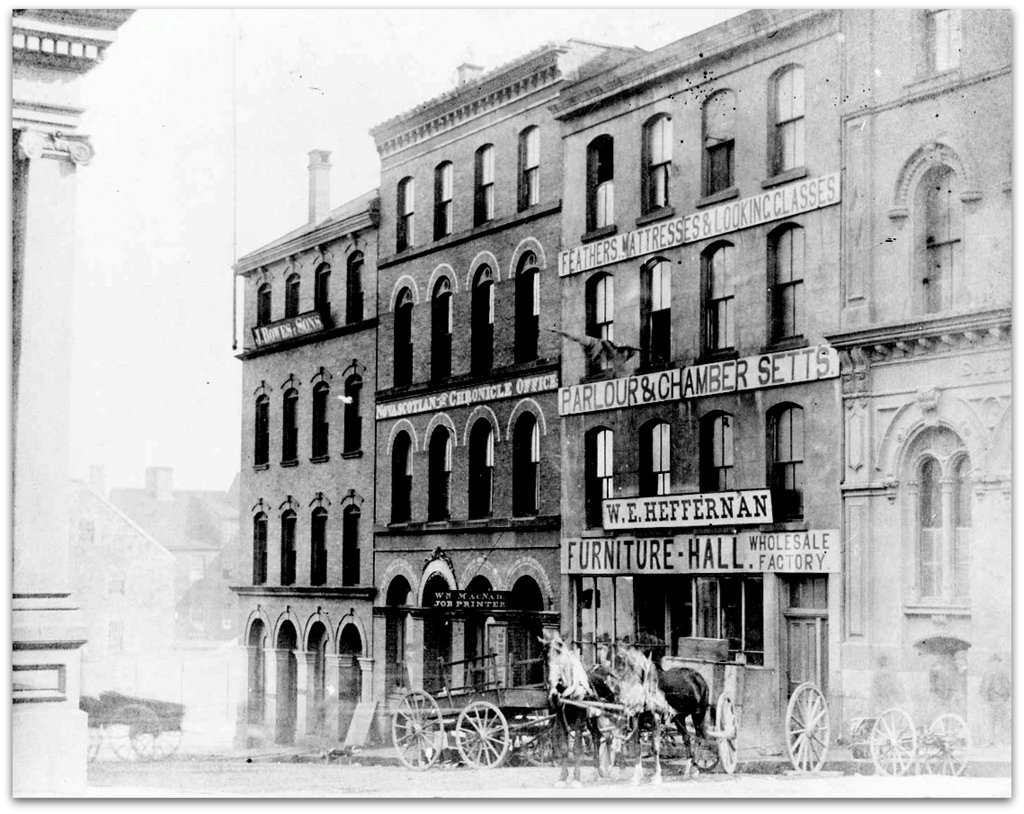

Fires on Prince and Hollis Streets a couple of years earlier had led to building a series of brick buildings that are now preserved as facades. Here is a view of the south side of Prince Street in 1871. Today the ground floors of the brick buildings house The Old Triangle Irish Alehouse.

Here is the corner building today.

The big fires led city council to pass a by-law requiring the use of fireproof building materials in the downtown area. As a consequence the area became known as the brick district. Gradually wooden buildings were replaced by ones of brick like this example that was on Sackville Street, now the SW corner of the Nova Centre site.

Many older brick buildings still survive but here are a couple we lost recently: this one was on Sackville Street and taken down for the Roy Project.

And of course the Roy Building itself, taken down for the Roy Project.

Brick and stone were the go-to fireproof materials in 19th century Halifax, but there was a moment when we could have embraced cast iron that was popular in the 1860s and 70s. Halifax has many cast iron shop fronts but only one complete cast iron facade – this charming building on Granville Street.

Another requirement in the Brick District was iron shutters on sidewall windows. This was to restrict fire from spreading from building to building. The last surviving set of these shutters I’m aware of are preserved on the Robertson Building of the Maritime Museum. (Get the shop boy to close them every night).

When we travel it is not uncommon to come to a new town and notice that the main street appears to have buildings all of the same time period (often helpfully marked with dates). This is usually a sign of urban renewal by fire.

Postscript

- The early success of the Shaw brick company was the result of them boldly purchasing new brick making equipment to help rebuild Windsor after fire devastated the town in 1897. Shaw’s also were big suppliers after the 1917 Halifax Explosion – urban renewal on a vast scale indeed.

- When renovating an old building it is not unusual to uncover evidence of fire. Government House had a major restoration a couple of years ago and a seriously charred beam was discovered. A little window was left in a wall so you can marvel at the near miss.

- Phyllis Blakeley in Glimpses of Halifax, the best history of late 19th century Halifax, provides some interesting background on volunteer firefighters. Seems there was an idea that aldermen were not necessarily the best people to be making decisions about fighting fires.

During the nineteenth century Halifax clung stubbornly to her volunteer Fire Department though towards the end of the century there were occasional complaints that trained firemen could direct the efforts of the volunteers far better than a Board of Firewards composed of Aldermen who might be good grocers or good judges of horses or building material and still know nothing about handling firemen or the best method of extinguishing a fire. Mayor J.C. Mackintosh reported in 1885 that ‘Halifax is old fashioned enough to prefer her extremely effective Fire Department composed of volunteers, to a paid department as now exists in most other cities…’