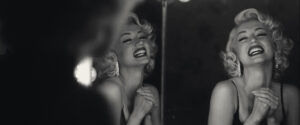

Blonde | Directed by Andrew Dominik | Written by Dominik, from a novel by Joyce Carol Oates | 167 min | ▲▲△△△ | Netflix

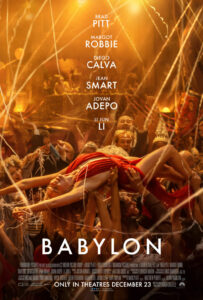

Babylon | Written and Directed by Damien Chazelle | 189 min | ▲▲▲▲△

I guess it’s just dumb luck I watched these two movies within days of each other, and couldn’t help but notice certain similarities. Both tell tales from old Hollywood fictionalizing actual people for the sake of a story, both are wide-eyed at the allure of the bright lights and clear-eyed at the (many) pitfalls of showbiz, both indulge a too-long running time, and both feature Brad Pitt — one where he appears as an actor and another as producer. At their core, both are big swings by respected filmmakers, but only one finds any measure of success.

Let’s talk about Blonde first, which dropped on Netflix a couple of months ago after making a big splash at the Venice Film Festival, the same fest that loved Joker, which should tell you something about how they like provocative pictures. The reviews for Blonde since more have seen it are some of the year’s worst — accusing the film of exploiting the memory of Marilyn Monroe and of a blatant male gaze in its storytelling.

It’s hard to argue against that perspective in a film where the lead character is treated so badly yet the camera constantly lingers on her face and body. From the very start, in Norma Jeane’s childhood, we have a deranged and abusive mother (Julianne Nicholson) beat her and try to drown her. It doesn’t get much better for her later on.

There’s also no arguing that as the adult Norma Jeane, Ana de Armas does great work, finding all the physicality we so identify with Monroe on screen and in photos — the transformation reminds me of what Kristen Stewart accomplished in Spencer — and full credit to her for delivering huge in emotional scenes, weeping every 10 minutes or so if not more. Unfortunately, de Armas’ Cuban accent does creep out from time to time, which I found hard to reconcile with what’s otherwise a convincing performance.

Blonde doesn’t hate its star, it pities her, but not since Amy have I felt as an audience member so turned into an accessory to the violence on screen. Dominik is implicating us in what we’re seeing — he’s telling us that by watching Marilyn Monroe we in the audience, along with the movie industry, the press, and the men in her life, we all share some responsibility in her exploitation.

On the stand I’d deny that allegation, but I wouldn’t deny what Dominik otherwise does with his camera: The film goes out of its way to recreate so many iconic images of Monroe in photographs and on film, flipping constantly between aspect ratios, film stock, and some of the most beautiful black and white imagery I’ve seen in a movie in some time. The visuals help drive home an affecting portrait of paranoia and growing mental illness — a scene where photographers and fans turn into grotesques is genuinely horrifying.

But what does it all amount to? A movie I’ll never watch again, and can’t in good conscience recommend — whatever its technical or lead actor’s achievements.

We’ve all heard about Norma Jeane’s ambivalence toward the image of Marilyn Monroe, that her on-screen persona was a performance she needed to put on in order to survive in the business, to give the audience what it was clamouring for. The lead in Babylon, Margo Robbie’s Nellie LaRoy, can’t wait to perform for her audience. As an actor, her character knows all the tricks, but there’s no schism between what she shows the cameras and who she is. She loves the attention, and lives for it.

Her enthusiasm is a lot of what gives Babylon its raucous spirit. That first hour, maybe 90 minutes, is a hugely fun rollercoaster ride of wild, frenetic editing, swooping cameras, and percussive, horn-driven jazz from composer Justin Herwitz, with Robbie mostly in the middle of the frame.

We’re dropped into the bacchanalia of 1920s Hollywood, the players who partied hard and worked harder. That opening party scene is something special, including as it does sex with a champagne bottle, the arrival of an elephant, and Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers in a monkey suit. It’s there where Nelly LaRoy makes the scene, and Manny Torres (Diego Calva) falls for her. He’s also scrabbling for a job in the dream factory, and he’s our eyes into this world, which director Chazelle can’t help but remind us: I don’t know if I’ve ever seen so many dolly in shots on an actor’s face. It’s a shame Manny is a bit of a cypher, otherwise, rarely driving the plot.

The rampant excitement of the party continues onto set the next day, with an uncredited Spike Jonze as the frantic European director setting up 10 cameras to get the shot of thousands of men in battle, barely stopping when an extra dies accidentally. In the middle of this is producer and star Jack Conrad (Pitt), drinking and carousing, making deals with Gloria Swanson and acting. It’s all something to see as the film somehow finds a way to evoke The Cannonball Run, complete with a stolen ambulance.

As in one of the versions of A Star Is Born sound arrives with a bang (and a great, disgusting audio gag) and we get a terrific scene of how the sets had to adapt, which included actors speaking, persnickety sound techs, and camera people sweating their asses off in sound-proof sheds.

It’s when the picture slows down that we start to understand it’s mostly smoke and mirrors. Manny rises to a position of power at the studio, but his unrequited affection for Nellie foreshadows his doom, while we check in with other supporting cast — good work from Jovan Adepo, Jean Smart, Olivia Wilde, Lukas Haas, Eric Roberts, and Li Jun Li — but we don’t really get to know any of them.

Pitt also never quite finds our sympathies — I’d point to his monologue with Katherine Waterston’s theatre queen as the moment where the film really starts to stumble, not to mention she’s really wasted. Robbie has all the fun, and this is easily her best role since The Wolf of Wall Street, which this picture almost matches in coke-fuelled party time.

The problem is that coke doesn’t let you down easy, and despite the movie’s relentless energy it can’t quite decide whether it’s Singing In The Rain or The Cotton Club or Boogie Nights. It ends up leaning heavily into the latter, especially in a segment with Tobey Maguire that really cribs from that classic Alfred Molina/”Sister Christian” scene.

Chazelle could have worse inspiration than PT Anderson, and while the final celebration of all things *movie* feels way too on the nose, it’s the ambition here that’s really admirable, not to mention a genuine love for American cinema of 80 years ago when Hollywood was a lot closer to the wild west.

Cinephiles will undoubtedly find something to enjoy here — after all, this movie is made for us.