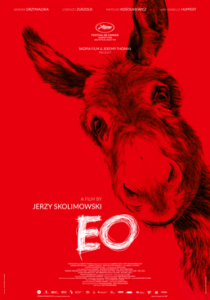

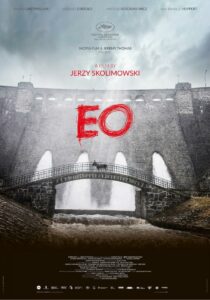

Directed by Jerzy Skolimowski | Written by Skolimowski and Ewa Piaskowska | 86 min | ▲▲▲△△ | Carbon Arc Cinema

Expecting to see this garlanded picture — it won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and is Poland’s official Oscar entry for Best International Film — I made a point to watch the film that inspired it, Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar, from 1966, now available on the Criterion Channel.

It tells the story of a donkey and the times and places he interacts with people, some who are kind to him and many who are cruel. He takes it all with an uncommon and phlegmatic grace. After all, he’s a donkey — they’re entirely unexpressive unless braying for one reason or another. His impassive nature serves to reflect our own character as apes of chaos, or sometimes just witness it. His fate is completely out of his control and entirely in ours, an inevitable victim of human beings’ arbitrary intent.

Skolimowski takes Bresson’s example as the jumping off point for his own exploration of what our relationship with animals says about us, telling his story with frequent red strobe effects and a lot of smash cuts.

At the film’s start EO the donkey is in the company of a circus performer (Sandra Drzymalska) who cares for him, but when animal cruelty protesters get the place shut down, the donkey is taken away from her to a farm where he meets a white stallion. The stallion gets washed down and well cared-for, while EO is ignored. He’s not there for long, soon escaping into the woods after briefly reuniting with the performer. Cue a 2001: A Space Odyssey-esque visual freakout before the next chapter, which involves soccer hooligans.

The film tempts us to ascribe anthropomorphic feeling on the donkey. I resisted it, you may wish not to. I don’t think the filmmakers want you to resist. There’s also the question of analogy — how much is the segment with the beautiful white horse about aesthetics, class, or the good fortune to be born a certain way? Eventually Isabelle Huppert shows up, though her story parallels the donkey’s and doesn’t intersect with it.

The real power of an animal like this, here and in Bresson’s film, is the deep vacancy in their eyes, which can be mistaken for depth of feeling or even calculated as such, depending on the score, angle of the camera, or the way the film is edited. You can read into this as deeply as you’d care to go, or give in to the filmmakers’ gentle authorial tug.

As a formal exercise in filmmaking, I largely enjoyed EO, but I didn’t feel much for the donkey. Perhaps I’m just a cold-hearted monster. It wasn’t until the final moments and his time amongst cows that I started to have a genuine sense of the character’s fear and uncertainty.