Written and Directed by Kenneth Branagh | 98 minutes | Crave

Belfast purports to provide a snapshot of actor-auteur Branagh’s youth in working-class Belfast, beginning in the summer of 1969 and the months following when sectarian violence exploded in his neighbourhood.

I couldn’t help but think of the parallels with the film I watched this week, Passing, also in black and white, also a period picture featuring a family where the father wants to relocate the family to protect the children from societal strife, and also already part of the Oscar conversation. But where Passing is an art house gem examining racial identity, Belfast is a shameless, lightly dramatic crowdpleaser.

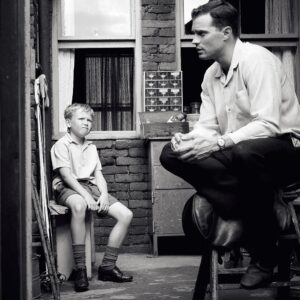

Buddy (Jude Hill, a revelation) is nine, raised by a village where everyone looks out for everyone. It would be the ideal childhood, filled with with cousins and crushes and math homework and Star Trek on the telly and regular visits to beloved Granny and Pop (Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds) if it weren’t for the start of the Troubles.

Militant Protestants are pressuring Buddy’s Pa (Jamie Dornan) to join in, to help “cleanse” the neighbourhood of those nasty Catholics. He’s barely around to help them, even if he wanted to, as he works in construction in England to support the family and pay off debt while Ma (Caitriona Balfe) takes care of Buddy and his older brother, Will (Lewis McAskie).

Branagh’s vision of Belfast starts in the present day in colour with something that looks like boilerplate tourism video, backed by Van Morrison, before it goes into the past in black and white, cueing more Van The Man. While I like the brilliant, grumpy Northern Ireland crooner as much as anyone — maybe a little less these days since he’s become an asinine Covid conspiracist — Branagh leans so hard on his music you’d think he had shares in his record label.

His film is also sweeter than rock candy. Scenes where Buddy goes to the movies and the theatre Branagh dabs in some colour — clearly meant to convey the magic of make-believe through his nine-year-old eyes — are hokey beyond belief.

Worse is the sketchiness in what goes on around the central family. The scenes with Dench and Hinds are delightful, but you get the sense Branagh could’ve brought more texture if Buddy spent time with other characters, allowing us to know them better — like the girl in his class who he likes (Olive Tennant) or even his brother, Will, who barely has a line of dialogue. Ma and Pa are confounded by their tax debt, but has Pa been misspending the money, gambling it, too? That subplot is unclear, and goes nowhere. I’m not sure it helps that Branagh avoids any political perspective on the violence going on around his characters, except to suggest everyone should just get along.

The real conflict here is between the Ma’s wanting to stay and raise her kids in this town, and Pa, who sees them having a better life elsewhere. And you kind of know who’s going to win that one.

I have to credit Branagh for his light touch, finding little moments of joy in the character interactions to help create this warm and frequently charming remembrance, with nicely chosen support in the neighbourhood from actors like Michael Maloney, star of the director’s lost gem, A Midwinter’s Tale, but there’s nothing especially like depth evident here. Belfast will speak to people for whom the baked-in cultural memory of a free range childhood really resonates, whether they had one themselves or not.