Leading up to the 2021 ceremony, I caught up on a few of the nominated features I’d yet to see. I’ve still got more, but here’s what I was able to get to this weekend.

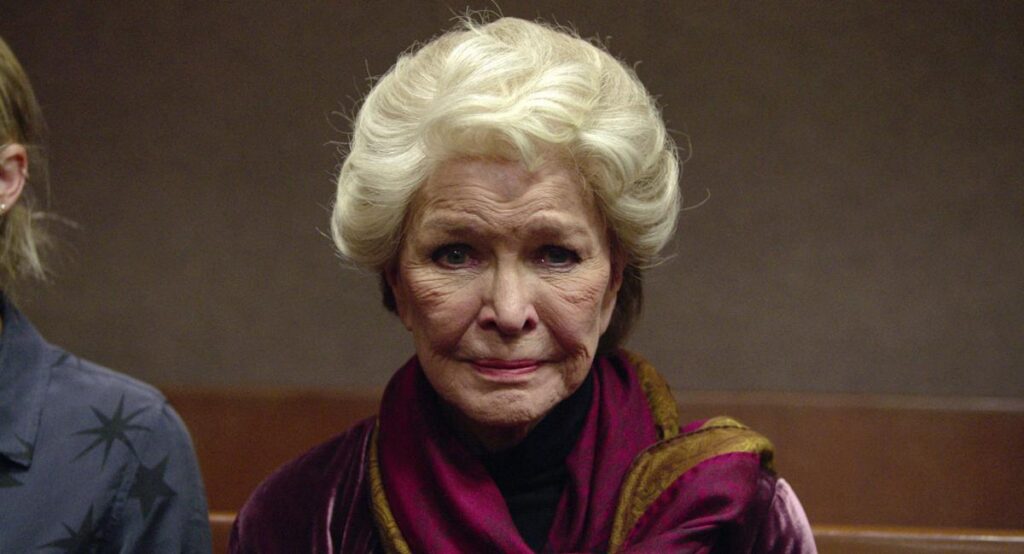

The United States vs. Billie Holiday | Directed by Lee Daniels | Written by Suzan-Lori Parks, based on the book by Johann Hari | 130 min | Netflix and On Demand

On the podcast I co-host with Stephen Cooke, LENS ME YOUR EARS, we have an episode on Music Biopics where we explore the many cliches of the genre, the Behind The Music-style rise, fall, and rise again narrative that we see over and over again. Drugs, fame, lovers, and managers who exploit— it’s no good for the creative temperament!

Make no mistake, Daniels’ (long) feature on Lady Day cleaves toward those genre tropes — it’s a melodramatic slog, favoring the heavy hand in the script rather than anything approaching nuance. It is better than the 1972 Holiday biopic, Lady Sings The Blues, with Diana Ross, though that’s not saying much.

What distinguishes it at all is how it focuses on Holiday’s efforts to promote civil rights and sing her most controversial song, “Strange Fruit,” and how that upset some white folks at the FBI. Knowing they can shut her down by booking her on her heroin use, she spends some time in jail, but that humiliation and injustice isn’t nearly enough to keep her from singing to people.

It turns out Holiday (Andra Day, Oscar-nominated and singing the songs herself) had an affair with the FBI agent, Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes, equally committed), who originally arrested her.

The film is clear-eyed about the overt racism of the era, the men who abused Holiday, and the way she internalized self-loathing and spread it around to the people closest to her. A watchable cast helps hold it together — including Da’Vine Joy Randolph, Rob Morgan, and Natasha Lyonne as Tallulah Bankhead.

One remarkable shot has Holiday walking through Times Square circa late 1940s — it’s really something to see, as are the costumes throughout. I wish I liked the film more overall. It’s just too fond of cliche.

(Right after watching the film, I dialed up the documentary Billie, from 2020, which gives another, fascinating take on her character through interviews with people who knew her.)

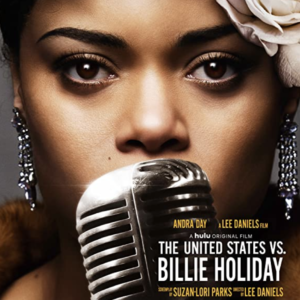

Pieces Of A Woman | Directed by Kornél Mundruczó | Written by Kata Wéber | 126 min | Netflix

Supposedly set in Boston, this film feels entirely like the city it was shot in, Montreal, with a grey, gloomy fall and wet winter snow.

It starts with a bravura 30-minute sequence of a home birth that goes tragically wrong. It’s a remarkable stretch of suspense, much of it in a single, uninterrupted shot. You learn all you need to about the couple, the mother, Martha (Vanessa Kirby, Oscar-nominated), and the partner, Sean (Shia LaBoeuf, convincingly damaged, but somehow difficult to sympathize with his hurt — kind of his brand).

The acts following, a full three quarters of the film, see the characters in the aftermath, with the pain of recrimination, infidelity, and more complications due to Martha’s controlling mother (Ellen Burstyn), a civil case against the midwife (Molly Parker), and the involvement of a family lawyer (Sarah Snook).

Between the ugly crying and the conspicuous shots of pubic hair, the film provides a moving, if messy, portrait of trauma, of the subsequent urge to blame, and how having forgiveness for others, and especially for yourself, is so important. Credit to Mundruczó and Wéber, partners in real life, for having effectively translated personal experience to their feature.

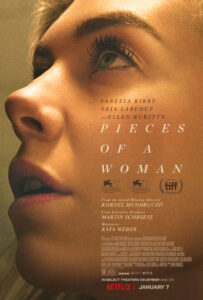

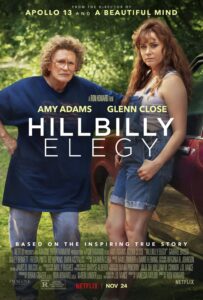

Hillbilly Elegy | Directed by Ron Howard | Written by Vanessa Taylor, based on the book by JD Vance | 116 min | Netflix

When the trailer for this picture dropped in 2020, the backlash on social media was loud and virulent. It might’ve had to do with the scenes of acting with a capital A — Amy Adams and Glenn Close in bad wigs yelling at each other— or it might’ve been the idea of a barefaced Oscar grab, deglammed stars and a rural milieu.

The funny thing is, despite all that and a host of awful reviews when the film arrived on Netflix, it worked: Glenn Close was nominated for Best Supporting Actress.

The film seesaws back and forth with dizzying rapidity between JD Vance’s present (when he’s played by Gabriel Basso) to his childhood (Owen Asztalos) in suburban Kentucky. In the past he and his sister (Haley Bennett) are raised by their emotionally fraught and sometimes drug-addicted mother, Bev (Adams), while their grandmother, who they call Mamaw (Close), also kind of a handful, tries to hold everything together. In the present, JD is a Yale student with an understanding girlfriend (Freida Pinto) interviewing for summer internships when his sister (still Bennett) calls him to say their mother just ODed and is in the hospital. He’s gotta come help out.

The frantic pace between scenes of outrageous behaviour mixed with not a little child abuse in the past — and yes, a whole bunch of Adams and Close yelling at each other — and the sudden crisis in the present barely gives the audience a chance to breathe. I feel like Taylor took all the book’s scenes of biggest tumult and just crammed them together in her script, making sure to tick them off one after the other. It also doesn’t make sense that the flashback material is spread out over time but the present day stuff takes place over the course of a day. It’s too much chaos.

If there was a chance for some real emotional wallop here, the picture refuses to let any moment sit before we skip ahead to the next big scene of someone throwing something. Let’s not excuse director Ron Howard. He’s a veteran filmmaker with a few good films (like Rush), and he should know well enough that this doesn’t really work.

Neither does Adams nor Close swinging for the fences in every scene. Howard is definitely responsible for not reeling them in. You can’t start at 10 — there’s nowhere to go. (Not even 11, sorry Spinal Tap fans.)

Finally, I can’t help but think the intention of this story was to humanize this troubled family, and maybe even deconstruct some of the damaging stereotypes about people living through hard times in middle America. This movie fails at that — sadly, it might even reinforce them.