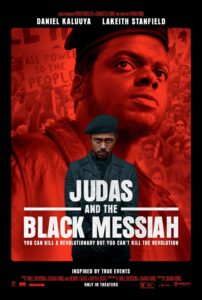

Directed by Shaka King | Written by King, Will Berson, Kenneth Lucas and Keith Lucas | 126 min | Crave Plus

The epic, practically Shakespearean crime dramas of Martin Scorcese, from Goodfellas to The Departed, cast a long shadow over Shaka King’s thriller and docudrama. It’s about the life of Fred Hampton, the young, charismatic leader of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers, set in the late 1960s. That Scorcese influence is both to the film’s credit and debit. While the history told here feels wildly and importantly relatable to the recent struggle for civil rights, and has all the grit in the telling and the spirit in the performances, King lacks Scorcese’s gift for suspense and narrative locomotion. The film is occasionally turgid when it should fly.

Let’s establish this important point: As Hampton, Daniel Kaluuya is a revelation.

We’ve known he’s good since before Get Out, but here he’s pure charisma. On the streets of Chicago he’s busy promoting the Panthers as a community group, bringing meals to children as well as getting the message across about their more forthright political action, as well as protecting Black communities from being harassed by the police. He speaks the language of revolution, but it’s also about helping people on the street, about connection with other marginalized groups. That attracts the attention of the FBI and its longtime leader, J Edgar Hoover (Martin Sheen under a distracting lump of prosthetics).

Car thief “Wild” Bill O’Neal (Lakeith Stanfield, convincingly conflicted) gets pinched by G-Man Roy Mitchell (Jesse Plemons, adding another creep to a growing collection), who offers O’Neal a deal — ingratiate himself amongst the Panthers and report back and he’ll be well paid and stay out of prison. At first, Mitchell’s able to twist the largely apolitical O’Neal by offering the false equivalency of radical politics, saying the Panthers are just like the Klan. Then, as O’Neal gets in deeper, Mitchell is able to continue to play him by threatening his exposure to his now brothers, and sisters, in arms.

O’Neal’s quandary, his deal with the devil, never gets any easier. His helplessness in the face of being controlled by his handler actually becomes something of a problem for the film. It demands compassion, but it doesn’t offer much in the way of dramatic escalation. It makes you wish Hampton was more the central character, and his romance with Deborah Johnson (Dominque Fishback) was the heart of the thing, the plot motivator. It’s great when the film spends time with them, but their story is too often shunted aside, and the supporting cast, the other Panthers, don’t get nearly enough time to register.

The film dramatizes the violent clashes between the Panthers and the police, as well as the ways in which Hampton was able to join forces with other community organizations. These moments end up being some of the best parts of the film, where we’re seeing the movement’s challenges and successes. The script is sharp enough to allow for an ongoing conversation about violence, and its limitations, even under the boot heel of oppression. We get a lot of those perspectives through the voices of the women in the story.

I admired much of it, but I wish I liked it more. Judas And The Black Messiah breaks one of the fundamental rules of screenwriting: its lead characters don’t really change over the course of the film, except due to the circumstances that affect their lives from the outside. It leaves us feeling like we’ve seen a snapshot of an important time, with an important message, but we haven’t really been on a journey with the characters.