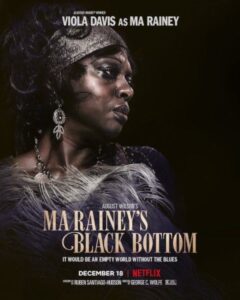

Directed by George C. Wolfe | Written by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, adapting the play by August Wilson | 94 min | Netflix

From the jump this is a straight-ahead stage-to-screen transfer that doesn’t do much to free the narrative from its theatrical roots. Right away that’s a strike against it — there aren’t many of these that don’t make you wish you were in the theatre seeing actors doing this in the flesh rather than what inevitably ends up a stiff, real-time, heavy-handed drama. I felt similarly about Fences, another recent Wilson adaptation.

But, here you’ve got a fiery concoction of materials that elevates it beyond the norm, telling the story of African American artists in Chicago one hot day in 1927 fighting for their identity, pride, and faith in themselves, while fighting against the white hegemony and each other’s expectations.

Then you’ve got the triumph and tragedy of the late Chadwick Boseman, who might be giving a career-best effort in his last appearance on screen, and Viola Davis, astounding and almost unrecognizable in make-up and costume, as Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, a real-life early blues singer.

Rainey is late for her recording session and her manager and producer, two white dudes (Jeremy Shamos and Jonny Coyne), aren’t interested in putting up with her “diva” behaviour. Well, one isn’t, the other is entirely obsequious. While the bandmates wait for her to show, they take shots at each other over song, style, ambition, and god. The youngest member, horn player Levee (Boseman), is the one with the biggest dreams and biggest chip on his shoulder — though when we get his backstory we see the size of that chip is justified, or at least explained, by a lifetime of trauma.

The music, produced by Branford Marsalis, is also terrific — it makes you wish there was more of it. Colman Domingo, Glynn Turman, and Michael Potts play the other fellows in the band, and they’re solid, too.

You may not be surprised to hear its the performances that make this worth seeing. The writing is a sometimes vivid, sometimes obvious road map, but if there’s anything here that makes this material feel universal, a heartbreaking portrait of a creative culture in oppression, it’s the people onscreen.

By the end you might forgive the on-the-nose symbolism of locked doors that lead nowhere, and instead be swept away by the immense charge of the talent giving it all.