Directed by Bong Joon Ho | Written by Bong Joon Ho and Han Jin Won | 132 min | Crave Plus

An earlier version of this review appeared on this blog back in September, when I caught this film at FIN Atlantic International Film Festival. It threw me for a bit of a loop—I wasn’t entirely sure how I felt about it. In the weeks since it’s settled in my mind, and I’ll join the chorus of reviewers saying it’s one of the year’s best movies. I’ve since seen it a second time, and have updated my remarks once again.

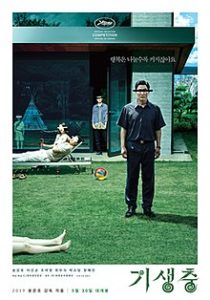

Parasite arrives anointed with the 2019 Cannes Palme d’Or, a unanimous vote no less. I’m not sure the picture could come with higher expectations. That’s not to say I’ve loved every Palme winner—I’m still scratching my head over Uncle Boonme Who Can Recall His Past Lives, and I was lukewarm over last year’s Shoplifters from Japan.

Parasite starts with some similarities to Shoplifters, but imagine if the Japanese drama was directed by Quentin Tarantino—that might give you a sense of its tone. Much like Tarantino’s films, you will not see where this is going, and it has violence waiting deep in its soul.

South Korean auteur, Bong Joon Ho (Snowpiercer, Okja), tells the story of a family of four living under the poverty line, and even underground, in a grimy industrial semi-basement. They’re a cunning and industrial bunch, though, and when the son (Woo-sik Choi) gets the opportunity to apply for a job tutoring English to the daughter (Ji-so Jung) of a wealthy family (also of four), he falsifies his credentials and ingratiates himself.

Before long his sister (So-dam Park), father (Kang-ho Song), and mother (Hye-jin Jang) have all found a way into this ultra-modern household, taking advantage of the wealthier family’s gullibility. There’s a sucker born every minute, and some of those suckers are also born into money, but the filmmakers won’t allow you the luxury of sympathy for anyone, at least not at first. Both families are products of their circumstances and prone to assumptions about the other that don’t necessarily line up. Both are victims and perpetrators, culpable and innocent.

More than that I won’t share, because the key joy here is the unexpected plot corkscrew, but what you can expect is a tar-black class study, with social commentary bleeding from every scene. It’s all deftly pitched and surprisingly grim as the filmmaker makes the remarkable look easy.

His mastery of tone is complete—the film’s opening act arcs toward farce, and at a single mid-scene party where alcohol is consumed, the central foursome take stock of their achievements and we get a sense of what is to come. Tension bubbles up, and the film changes into something more akin to a thriller. The allegiances are tested and something like instant karma arrives in the end. A second viewing peeled the plotting back to reveal the film’s deep feeling. I won’t say it’s a necessity, but it helped me appreciate the emotional impact.

The universal relevance of this material is so white hot, you can’t quite stare right at it without blinking. If you walk out of the cinema covered in blood and slightly abashed, don’t be at all surprised.