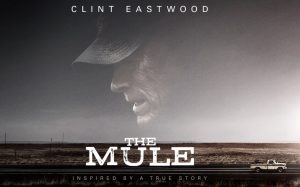

Directed by Clint Eastwood | Written by Nick Schenk from an article by Sam Dolnick | 116 min | Netflix

Clint Eastwood is tireless. At age 88 he’s still acting, directing, and producing feature films, and while he’s been criticized for both his politics and his casual way with detail—the fake baby in American Sniper comes to mind—he’s still a storyteller to be reckoned with. The Mule is a throwback to the kinds of films he made in the 1970s—a mix of tones and genres, with a winning simplicity in its characterization.

It’s based on the true story of senior citizen, florist, and veteran Earl Stone who, alienated from his family (including ex-wife Dianne Wiest, daughter, also in RL, Alison Eastwood, and granddaughter Taissa Farmiga), gets involved with drug cartels. He’s hired to move product from Peoria to Chicago, Illinois. The film is non-specific, but that’s only a two-and-a-half hour drive—I guess they still need drivers who aren’t likely to get pulled over, and who wouldn’t trust this easygoing older fellow? Naturally, carrying pounds of narcotic across the state makes Earl’s bank account a lot healthier, and his life much more complicated.

The picture sets up a dreary thriller around a very vulnerable-looking guy—there’s no way Eastwood could pull off any kind of action sequence at this point in his life—and then delivers a story surprisingly at ease with its many moods, moving from family drama to ribald humour to thriller. Though the film was written by Schenk, who also worked with Eastwood on the controversial Gran Torino, this picture is far more whimsical at its heart.

Laughs are generated by Earl’s being totally out of touch with life in the 21st Century—Earl hates the internet, naturally, and has never met a lesbian on a motorcycle before. Aside from his angst around having worked too much and neglected his family, his modus operandi is to have a good time all the time. That means not one, but two scenes suggesting threesomes. Yeah, that’s right.

And check out the scenes at the DEA, where agents Bradley Cooper and/or Michael Pena walk into the office of their boss, Laurence Fishburne. The pacing of those scenes feels like something Eastwood picked up from Don Seigel. The actors enter the room, speak, and then leave. No one shoots or cuts scenes like that anymore—the actors are already in the room, mid-conversation, and if they arrive, they don’t leave before we cut away. The way Eastwood does it is both strangely antiquated but still kind of charming, and, somehow, it all works for this loping caper. Eastwood is also famous for shooting quickly, with two or three takes at most before moving on, giving The Mule a spontaneous energy. If line-readings are a little flubbed, Eastwood’s OK with that if the scene otherwise works.

Something else worth considering, and that’s the ways this film mirrors Eastwood’s own life and career. There’s no doubt he spent his life working, and maybe he wasn’t the most present family man. Consider the stories about Eastwood generated in the ugly disputes between him and his ex, the recently passed Sondra Locke. It wouldn’t be hard to believe he lives with some regret. There’s nothing here to suggest this explicitly, but it brings a little added gravitas to the story if you want to go there.