Another terrific season at Carbon Arc Independent Cinema is drawing to a close. I wasn’t able to get to all the films that screened in the past few months—Cielo, Nico 1988, Summer 1993, and Breath remain unseen by me—but please find the following reviews of the films I was able to see, including this Friday’s The Guilty, my review from FIN Atlantic International Film Festival. Carbon Arc will return on February 1, 2019.

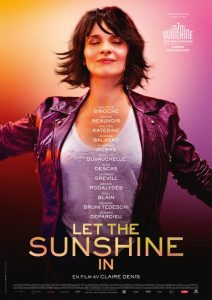

Let The Sunshine In

Someone in the crowd at Carbon Arc criticized the film saying it was too much like Woody Allen. I disagree. Allen never has this much sex in his movies. In Clare Denis’ 2017 romantic dramedy, Juliette Binoche is Isabelle, a 40-something painter living in Paris. Her life isn’t all glamour and gallery openings—she’s mostly just obsessing over a series of men, most of whom treat her badly. It’s as if she can’t quite stay away from the ones who are less than reliable, and instead finds herself replacing one with another, none of whom are interested in commitment. The romantic existentialism is slightly depressing, because despite the fact the cast are all in their 40s and 50s, no one seems to have advanced emotionally from their 20s—but maybe that’s where the humour comes in. Let The Sunshine In is too scattershot to lodge in the brain for long, but whimsical and charming enough to have left an impression, with the welcome reminder that Binoche just gets more potent and more sexy with the years.

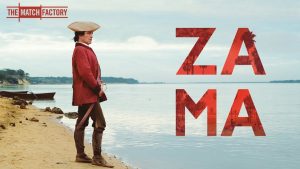

Zama

Lucretia Martel’s peculiar picture tells the story of a 17th Century Spanish bureaucrat stuck in some god-forsaken riverside town—Asuncion in the novel it’s based—desperate to be transferred to a better post, to be closer to his wife and family. As he waits for the appropriate orders he does a delicate social dance with the other perspiring colonial populace as they mistreat the indigenous population, live among dogs and horses and llamas, while tropical maladies reduce their numbers and tales of banditry sew fear. I had the suspicion a gentle push could turn all this into Mel Brooks territory—in places it goes for full-on absurdity and a wild-eyed Herzogian misanthropy. Don Diego de Zama (Daniel Cacho) is anxious and sexually frustrated, and in that there’s humour to be found. The Carbon Arc audience members I spoke with enjoyed the film, but I found it a bit of a slog. I confess that (due to circumstances not worth going into here) I missed about 25 minutes of the 115 minute run time, so please consider this an impression rather than a proper review.

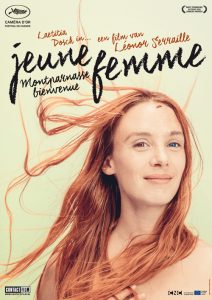

Jeune Femme

Otherwise known as Montparnasse Bienvenue—depending on the market—this is the first film from Léonor Serraille, who won the Golden Camera at Cannes, the award for best debut feature. It’s a character study: Paula (Laetitia Dosch) is in her early 30s, and a free spirit. Jobless, she steals her ex-boyfriend’s cat and sets out to find herself both accommodation and employment in Paris. She’s a little self-sabotaging, she infuriates as much as inspires, but she also has the courage of her convictions. She somehow lands a gig as a live-in nanny to a lonely tween, and a job at a fashion boutique, though both of those situations are precarious. Floating in the background is her soured relationship with her mother, which has gotten so bad Paula is banned from the homestead. What could she have done to alienate her own mother so completely? Paula may be finally finding some measure of maturity following a youth of terrible decisions. She’s not lovable, but nevertheless the film compels in its fragmentary editing and intimacy. It refuses to take a straight line between two plot points, a little like its protagonist. It leaves Paula in a better place than it found her, but nothing about her journey, or the film, is easy.

Hearts Beat Loud

Imagine if Barry Judd, Jack Black’s character from High Fidelity, finally grew up, got together with someone, became a father, and opened his own record store in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Twenty years later he’d probably be Frank Fisher, the guy Nick Offerman plays in Hearts Beat Loud. Frank still runs the record store, a space he rents from Leslie (Toni Colette), but he’s shutting it down. Time for a change, he thinks. His daughter, Sam (Kiersey Clemons) is heading to UCLA in the fall to do pre-med. In the evenings they jam, and make pretty great music. (Clemons has a gorgeous voice.) Oh, and Frank’s mother (Blythe Danner, cornering the market in older ladies with dementia this year) is prone to shoplifting, and Sam is spending her extra time getting friendly with Rose (Sasha Lane). One more character to mention: Ted Danson plays a philosophical bartender. It might not be in Boston, but the echoes are unmistakable, and delightful.

It would be a mistake to rave about this film, not because things about it aren’t rave-worthy, but because it’s way too gentle and unassuming to be comfortable with anything like a rave. The film delivers truisms, like, “you’ve got to be brave before you can be good,” and “you can’t always do what you love, so you gotta learn to love what you’re doing,” at timely intervals. Its stakes are resolutely set on medium generational-schism, simmering middle-aged-man-gets-schooled-by-his-more-mature-teen-daughter, and summery-Brooklyn-ease, with a pace is as unrushed yet hooky as a Jeff Tweedy song—look out for the Wilco front-man haunting the picture.

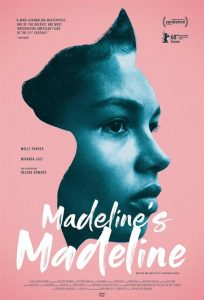

Madeline’s Madeline

Jospehine Decker’s feature has been called “experimental,” but that’s not the first thought I had about this mother-daughter, mother-mentor drama. To me it just felt like the natural extension of a certain brand of New York indie picture—the story of a teen, Madeline (Helena Howard, remarkable), who gets involved in an improv theatre troupe led by a warm but domineering creative (Molly Parker), while her relationship with her helicopter mother (Miranda July) is fraught, partly because the teen has suffered from some past emotional disorder requiring care and medication. The coming-of-age tropes didn’t feel very fresh, but Decker slowly gives us a view into Madeline’s head using a lot of handheld camera and editing. The truth of it is I felt her empathy for her characters—and the performances are excellent across the board—but ironically I never felt much for Madeline herself. She rebuffs our interest in her, and twists away into some kind of aesthetic madness that’s neither frightening nor moving.

Science Fair

A wonderful documentary about brilliant, ambitious teens looking to save the world with their inventions. The doc travels to Germany, Brazil, and all over the United States to visit nine teenagers at home, some as young as 14, while they prepare for the International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles—sort of the Academy Awards for geeky, brainy science nerds—and then follows them to the big show. The film peels open the lives of these kids, and even when some of them aren’t supported by their culture or their schools, they still wind up achieving great things. The picture ends up being both hilarious and touching, wonderfully hopeful about the future. One of the Carbon Arc attendees commented afterward, “Maybe we will be OK after all.”

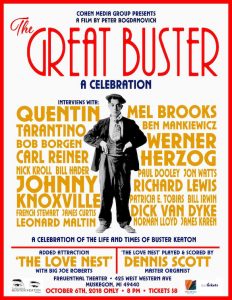

The Great Buster

A wonderful primer to the work of Buster Keaton from Peter Bogdanovich, split between the story of Keaton’s life, samples of his remarkable films, and testimonials of his admirers, friends, and family. Unconventional it is not, but it manages to get the message across that he was a peerless performer and filmmaker, and helped build the foundations of cinematic comedy. Structurally, one of the interesting things it does is recognize Keaton’s most fruitful period, the mid-1920s, and then skips over that to tell the story of his harder, later years, then, in the final 20 minutes, goes back and celebrates those great works.

The Guilty

A Danish thriller that reminded me quite a bit of Steven Knight’s Locke, though in some ways director Gustav Möller has set himself an even more challenging dramatic scenario, because at least Knight could shoot something in motion—a car—and Knight also had the immense charisma of Tom Hardy to work with. Möller’s film takes place entirely in a room—well, two rooms, to be completely accurate—and 90 percent of the imagery is his lead’s face.

Jakob Cedergren is Asger, an emergency response operator, basically who you get when you reach Danish 911. He gets a call from a woman claiming to have been abducted by her ex-husband with a criminal record. Asger oversteps the boundaries of his job and starts investigating this couple’s past and children, and before long we understand his motivation to help is driven by the guilt he feels over an incident that happened when he was a patrol cop.

It’s suspenseful stuff, with extraordinarily fine sound work deftly creating the world in those phone calls. Props to Cedergren, who has to do a lot of heavy lifting with his face.