Written and directed by Greta Gerwig | 94 min

Greta Gerwig, the queen of the New York indie—witness Frances Ha, Mistress America, and Maggie’s Plan—takes her turn as a writer/director in this tale of a willful teenager in the wilds of 2002 Sacramento, California. Tonally very much of a kind with those movies she’s starred in, including a light dash of 20th Century Women in the sun-shiney, west coast vibe, though not in the look: Gerwig prefers a grainier visual approach, a shoestring aesthetic.

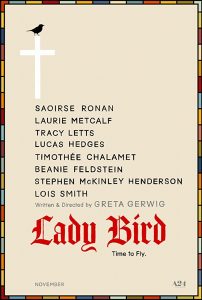

Lady Bird is the name Christine (the dependably impressive Saoirse Ronan) has given herself. She’s a rebellious outsider at her suburban school, all entitled teenage attitude beneath poorly dyed burgundy hair. She’s sick of her little town—she wants to go to the east coast where she hopes to find real culture—and she’s sick of her mother (Laurie Metcalf, always welcome), who she loves but feels is always holding her back.

We spend a year with Lady Bird and her family as she does a little growing up and crams in a lot of events—rejecting the Catholicism of her high school (embodied by the nun played by the excellent Lois Smith), jumping into theatre, trying drugs, finding a boyfriend (or two), hanging with her BFF Julie (Beanie Feldstein), rejecting Julie, making new friends, and managing a stressful home life; her father (Tracy Letts) struggling professionally, her goth brother (Jordan Rodrigues) and his live-in girlfriend (Marielle Scott) giving her grief, and the never-ending cold war with her mother.

The tang of these teen experiences is sharp, and there’s not a single weak link in her sprawling cast—they’re all vivid and believable. Metcalf, Letts, and Hedges are especially good, and Lady Bird’s love interests, Lucas Hedges and Timothée Chalamet, are exactly who they should be. There’s a palpable charm here, and Gerwig’s confidence as a director feels earned.

But while I enjoyed a lot that goes on here, I didn’t fall in love with Lady Bird, and I’ll tell you why: it’s too detached. Everything in Lady Bird’s life hits like we’re watching her own personal sitcom, even when she ends up in the hospital due to overindulgence. As with most American movies in the past 30 years exploring teen life it owes something to John Hughes, but it refuses to take Lady Bird’s trauma as seriously as Hughes did his characters’—it’s as if Gerwig wants us be a witness from a safe, ironic distance. We don’t ache in her character’s mistakes and we don’t thrill at her victories. If this picture was an album it would be the greatest hits of adolescent upheaval, missing the deep cuts.