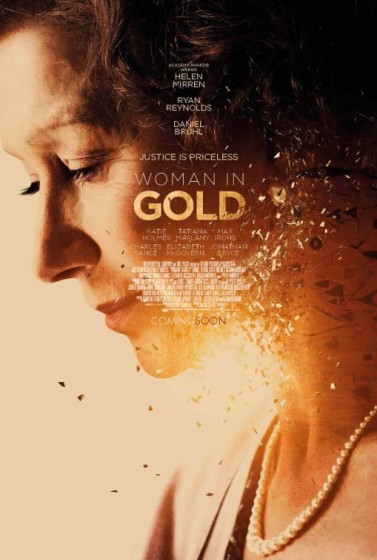

Directed by Simon Curtis, written by Alexi Kaye Campbell, based on the story of E. Randol Schoenberg and Maria Altmann

Sometimes a story is powerful enough, and a cast potent enough, that it overcomes the poor choices of a movie’s screenwriter and director. This is one of those times.

Based on the actual tale of an Austrian immigrant who fled Europe for the US before the war, who fought the Austrian government to reclaim paintings by Klimt stolen from her family by the Nazis. Living in Los Angeles, Maria Altmann (a typically stellar Helen Mirren) engages Randy Schoenberg (Ryan Reynolds), a lawyer who happens to be the grandson of the famous Austrian composer, Arnold Schoenberg, to explore the possibility of getting the paintings back, including the famous The Portrait of Adele Block-Bauer, who was her aunt. Cue an odd couple adventure, one that takes the mismatched pair to Vienna, as the Austrians fight to hang onto their ill-gotten but nationally prized paintings.

Along the way we get frequent flashbacks to Maria’s life as a child and young woman (played convincingly by Orphan Black‘s Tatiana Maslany) in Vienna, her family’s sumptuously appointed apartment with its collection of masterworks, and how their lives fell apart when the Nazis started to persecute the Jews in the city.

The script is where the clunkiness lies. Screenwriter Campbell has no fear of cliche or exposition, and accordingly ladles it on thick. The obviousness of the word choices grates on the ear, with scene after sentimental scene going exactly where you expect. And director Curtis doesn’t help—he finds some quality locations and lights his actors well, but doesn’t really know where to put his camera much of the time, creating a film that has next to no visual pizzazz. And he wastes pretty much everyone but the leads, including Charles Dance and Daniel Bruhl, and poor Katie Holmes, reduced to the mostly silent supportive spouse. I spent swaths of the movie daydreaming about how whole scenes would have worked better if the filmmakers had applied a little more verve and imagination. That’s a pretty bad sign.

But Mirren plucks as many feisty grace notes as she can as the spry octogenarian looking for justice, without any real hope that the Austrian government is going to hand over paintings worth hundreds of millions of dollars. In some ways, Reynolds has the tougher job—his Schoenberg starts mild and anxious, but in advocating for Altmann finds a connection to his own Austrian past, and ends up delivering a fairly moving performance of his own.

It’s hard to go wrong with such a rich and personal story of survival and justice, born out of the horrors of the Holocaust, no matter how conservative or kitschy the telling. So even though the script and direction play it safe and, frequently, dull, with the help of Mirren and Reynolds (and a solid score by Martin Phipps and Hans Zimmer) the emotional beats of the piece do end up translating.

Sometimes the source material wins out, whatever kind of tube the paint gets squeezed from.