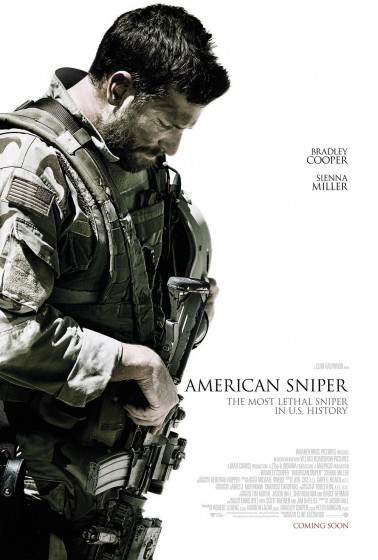

Directed by Clint Eastwood, from the book by Chris Kyle with Scott McEwen and Jim Defelice

Films about the war in Iraq haven’t been embraced by the public. Consider The Hurt Locker, which still holds the record for an Academy Award Best Picture winner with the smallest box office.

There are any number of reasons for people not going to see movies about the Iraq War, and they should be pretty obvious in this era of spectacle and escapism at the cinema. And, just maybe, aside from the picture mentioned above, movies about Iraq haven’t been terribly memorable so far.

Now we have American Sniper, which in one day doubled The Hurt Locker‘s entire haul. (Here are details about Friday’s big numbers.) Generally I’m not too bothered by the business of show, but this is a zeitgeist picture, and I want to understand it. Why the huge appeal?

My pet theory: American Sniper takes the story of a complicated guy who fought in a complicated war and smooths it out for a conservative audience that prefers a tale to fit its values. In that regard, American Sniper is a more sophisticated Rambo: First Blood Part 2. That’s not to say it’s anywhere near as broad or cartoonish as that Stallone picture, where his musclebound veteran returns to Vietnam to rescue POWs and kill a lot of folks, but it seems to be tapping into a similar need. It’s making audiences feel better about the American time, money, and lives spent in an unpopular conflict. There’s no ambiguity: Chris Kyle is the soldier who wins the war.

In the real world, Kyle was a decorated veteran of the conflict, having gone to Iraq on four tours as a SEAL. He is reported to have killed more enemy combatants (160 confirmed, though he claims it was more like 225) with his high-powered rifle than any American sharpshooter in history. After his duty was complete, he was killed at a rifle range in his home state of Texas while spending time with another young veteran.

He was also someone who lied to burnish his reputation. At the very least he was a complex individual, though complex isn’t how I’d describe the guy Bradley Cooper portrays. Cooper’s character isn’t the self-aggrandizing warrior Kyle is said to have been—the onscreen Kyle is humble, uncomfortable being called by his nickname, The Legend.

And there’s absolutely no ambiguity in how he sees his mission, which is to protect his team from the rooftops and kill the enemy. To him, insurgents are savages and he is totally justified in ending as many of their lives as is necessary. The particulars of why he’s there, whether he and his fellow soldiers were actually helping the Iraqi people, whether the mission is even worthwhile, are never broached. And that’s probably fair when you tell the story of a soldier: When your country says you go, you go. You don’t ask why. Soldiers need to be good at taking orders. But the movie could have provided a bit more insight.

We repeatedly flash back to Kyle’s life in the States, starting with his childhood. His father taught him a particularly American view of the world that explains a lot of US foreign policy: There are three kinds of people, Wolves, evil-doers who prey on the weak, Sheep, who just go along with the crowd and get preyed upon, and Sheepdogs, who protect those who can’t protect themselves. Kyle was raised to be that third thing.

In his 20s he was a cowboy rodeo rider, “living the dream”. After 9/11, that wasn’t enough anymore. He signed up to be an elite soldier, went through the hardcore bootcamp, became a SEAL. He inspires his younger brother, Jeff (Keir O’Donnell), to sign up as well.

Kyle meets Taya (Sienna Miller) in a bar during basic. Within three or four scenes they’re married. He gets his orders at their wedding. She’s ready to settle down, and he’s ready to go to war.

I’m a fan of Eastwood’s methodical, no-fat directorial style, but the just-the-facts-ma’am telling of how the couple gets together feels like the Coles Notes of a real relationship. It helps that Cooper and Miller are both game, injecting more nuance into their scenes together than the script or direction offers.

But American Sniper really catches fire when we’re in Iraq, as Kyle and his SEAL team track down an Al Qaeda leader known as The Butcher (Mido Hamada), while avoiding the raining death brought by Kyle’s opposite number and nemesis, the Syrian sniper Mustafa (apparently an entirely fictional character, played by Sammy Sheik). Through Kyle’s four tours we get a procedural on how the US soldiers got things done in urban centres like Fallujah and Sadr City, and how Kyle’s deadly talent was put to use. The attention to detail, the nuts and bolts of life on the hunt—the suspense never lets up. This is where American Sniper works most effectively, and most resembles The Hurt Locker or Black Hawk Down, the best modern military pictures.

It’s here where Cooper’s talent, his ability to be expressive while saying very little, is put to most potent use. As time passes he and his team become hardened and frustrated by their losses, painting Punisher logos on their armour and vehicles. The cumulative costs on their psyches, if not their bodies, are huge.

Then, every time we go back Stateside, things grind to a halt. Kyle experiences a disassociation with ordinary life and struggles to reconnect with his wife and kids. The dialogue is soapy and on-the-nose, with repeated scenes of Taya trying and failing to get through to the man she married. Those are key elements that, unfortunately, feel trite.

What’s most disappointing is Kyle never actually admits he has PTSD. We see he feels stress when he comes home, he acts strangely once or twice. But he avoids the possibility of trauma when he sees a doctor. According to him what hurts most is he couldn’t save more soldiers in the war, so when he does start to spend time with veterans and finds a way to feel useful again, his personal problems are easily solved. No word on Jeff, his brother, whose experience in Iraq was more negative. He vanishes from the film after a brief second act appearance, never to return.

Maybe it’s a fact that Kyle wasn’t clinically burdened by that kind of affliction, but given the high rates of suicide in the US armed forces, the film misses the opportunity to genuinely demystify unseen trauma. The vets Kyle meets are physically wounded, but the film dances around any mention of potential mental illness.

This is despite the fact the vet who shot Kyle apparently suffered from PTSD. There’s no effort to explain why that happened, which leaves a weird absence at the film’s conclusion, and, I’d argue, through the entirety of its last act. (If you’re curious about how Chris Kyle’s life actually ended, much more is revealed in this article.)

The bottom line is this: The movie does some things well, and where I don’t necessarily agree with its historical perspective, I found it a gripping story of war. I just couldn’t help but think there was much more good it could have done if it had been willing to go a little deeper.

UPDATE: Tuesday, January 20, 2015

Today I found the answer to at least one of the questions I had about American Sniper. The reason Eastwood doesn’t get more into the story of Eddie Ray Routh, the guy who confessed to killing Chris Kyle, is because the case is still before the courts. According to this article, Routh is going to plead not guilty by reason of insanity, and the movie’s ubiquity could make it difficult for the accused to get a fair trial. That does complicate things.

One other thing I wanted to say about this picture. I’ve been fascinated by its huge success, and have read with a mix of curiosity and, on occasion, disgust, the reactions to the movie, much of it along political lines. But this evening I can’t contain my delight at how the online conversation has now been taken over by #FakeBaby (see below).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fLwAcU0bYl0

I hope people on the right and left of the issue take this chance to show they have a sense of humour. It is, after all, only a movie.