Directed by James Marsh, written by Anthony McCarten, adapting the book by Jane Hawking

Odd confluence trivia of the season: The science advisor for Interstellar, Kip Thorne, is a character in The Theory of Everything, played by Enzo Cilenti. He’s the guy who gets the Penthouse magazine subscription with Stephen. To bad 70s mens magazines didn’t play much of a role in Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster—Thorne could have advised on those, too.

I’ve made no secret of my reluctance for biopics. They tend to be stolid, sentimental tales of important men and women maybe worth seeing once and never again—even the good ones. When I’m sitting through a biopic I always ask myself: Would a documentary on the same subject be more engaging?

In this case I can safely say no. The Theory of Everything delivers for two strong reasons:

1) Though Stephen Hawking is the man who people might enjoy knowing more about, the story is told from the perspective of his first wife, Jane.

And 2), the performances are as good as anything I’ve seen this year.

The Theory of Everything is a gentle, well-made tale of a remarkable scientist who overcame an extraordinary obstacle to his health, ALS, to change the way we think about the universe. But more than that, it’s a love story.

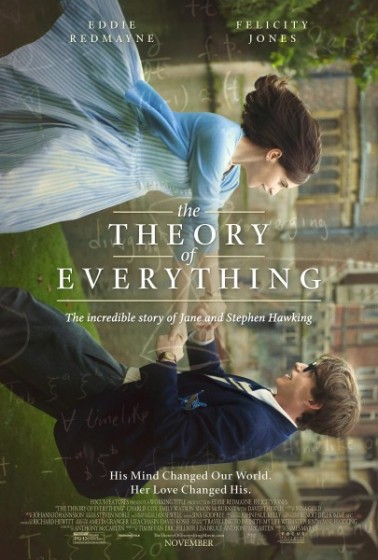

Eddie Redmayne is Stephen Hawking, who back in 1963 was an awkward but promising student at Cambridge University in the UK. He has enough confidence to ask out Jane (Felicity Jones, matching Redmayne beat for emotional beat), even though she’s a churchgoer studying medieval poetry and he’s an atheist fascinated by the workings of the universe. Whatever differences in their values, the couple get together quickly and stay together, even when Hawking is diagnosed with motor neuron disease and given two years to live.

Somehow he proves the doctors wrong, though it’s never really explained how it is he manages the longevity. Hawking’s ALS is a key part of the plot, but it swiftly becomes a backdrop to the shifting sands of the couple’s marriage. Jane winds up having to take on the responsibility of raising their three kids, and taking care of Stephen as well. It all becomes too much for her to handle. They meet a friendly local music teacher (Charlie Cox, oozing warmth) who becomes their de facto extra caregiver, but that situation complicates rapidly.

Cox is solid in the role, but aside from him a collection of thinly drawn characters helicopter around the lead couple—Hawking’s professor, played by David Thewlis, his scientist friends, parents, and Jane’s mother, an underutilized Emily Watson. At its best, the film is a two-hander.

But what hands: Redmayne, best known as Marius in Les Miserables, proves equal to the herculean task this role requires, a Day Lewis-esque effort of physical transformation as he becomes, before our eyes, the Stephen Hawking so familiar to us today. It did make me think of My Left Foot, except Christy Brown was such an angry man, while Hawking’s sense of humour barely flags as he goes from walking to a wheelchair and slowly loses the ability to speak, all the while finding ways to manage his diminished physicality. Redmayne does a lot of acting with his eyes.

Jones is so good, too, in the most British of roles: Her Jane is an individual of indomitable will who must maintain her stiff upper lip, damn the torpedos and whatever her husband is going through, though at no time do we ever have any doubt of the range of powerful emotions beneath her surface.

Marsh applies the swelling strings as required, occasionally switching into faux Super 8 for the home-movie sequences. The film is shot and edited with grace, and even while it does that thing that I never like in biopics—covering great swaths of years, piling up the unconvincing old-person make-up on the actors—I found the storytelling deft and compelling.

Subjects such as of quantum mechanics and relativity surface regularly while the the film manages to deliver the reality of time’s passage through the characters’ lives. That’s a clear thread, and there is some effort to make the science and math understandable to average-sized intellects like my own. I confess I didn’t get all of it.

If I had to besmirch The Theory of Everything for any one thing, I would remark on its conclusion, which takes a turn or two towards the trite. That said, none of this was enough to capsize the experience, and it’s hard to imagine these performances being overlooked come golden statue time.

• For another take on part of this story—Hawking’s time at Cambridge—a 2004 BBC production called Hawking is available to be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, starring Benedict Cumberbatch. Go here to see it.