Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Aronofsky and Ari Handel

This isn’t your daddy’s Biblical epic. That was my first thought as I waded into Noah, the $125 million blockbuster from the indie director of Black Swan, The Wrestler, The Fountain and Requiem for a Dream.

For awhile Aronofsky was attached to The Wolverine—imagine what that would have been like. Instead he went off and made this. And while I can’t say it had me engaged throughout—it could easily lose probably 20 minutes of its running time—what impressed was that Aronofsky has his cake and eats it to: He works within the framework of a story everyone knows, one that should please many of its faithed-based audience, and still manages to update it as a relentlessly sincere post-apocalyptic journey, laced with messages about environmentalism and vegetarianism, with a shot to the throat of fundamentalists, too.

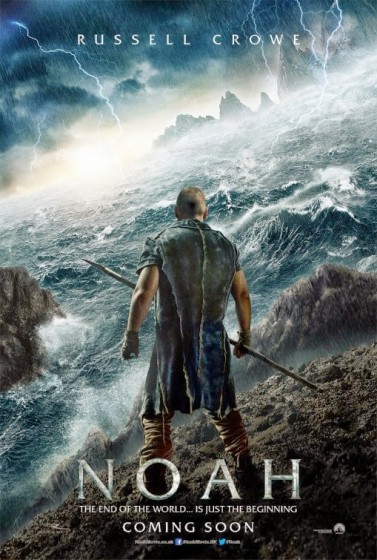

Noah (Russell Crowe, taciturn to the point of cliche) is the paterfamilias: three sons, Shem (Douglas Booth), Ham (Logan Lerman) and Japheth (Leo McHugh Carroll), and wife Naameh (Jennifer Connelly), all apparently the last of the descendants of Seth, one of Adam’s decent sons. We learn the descendants of Cain (lead by the volcanic Ray Winstone’s Tubai-Cain) have gone and poisoned the planet with their rampant cities and poor resource management. The Creator is angry, but allows Noah a vision—he must build an ark to save the innocent, everything that creeps, crawls and flies. We also learn that the Creator was pissed off with the angels, consigning them to live on earth as rocky monsters with Nick Nolte and Frank Langella’s craggy voices matching their exteriors.

Structurally, the film is divided into chapters: Noah’s family’s journey through the wasteland—where they pick up a young girl who grows up to be Emma Watson, a love interest for Shem. Noah meeting his grandfather Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins), who lives in a cave in a mountain. It did occur to me that Thor’s father is Jor-El’s grandfather, and Jor-El begat Percy Jackson and adopted Hermione Granger. The superhero epic, the Young Adult fantasy, all so much a part of our culture now, is peopled with now-iconic actors who bring a certain gravitas to whatever else they work on. I’m sure the producers of Noah had all that in mind when they chose their cast.

Then there’s the ark building, the conflict with Cain’s hordes in the torrential rain—which reminds me of nothing more than the Battle of Helmsdeep. That’s followed by the 40 days and nights aboard the ark, and the conflict between Noah and Ham, when Noah’s unwavering righteousness turns him into the story’s antagonist.

This may be the part of the film I liked best. Tunai-Cain and his people have been shown to be a hoard of faithless individualist carnivores, while Noah and his family consider the community of humanity, take “no more than they need”, and don’t dig on swine, or anything else with a pulse. But Ham, and the rest of the family, for a lot of good reasons, feel like dad’s take on the Creator’s plan is a bit narrow, in that he believes humans shouldn’t survive at all. And as they go along, Noah’s rigid interpretation of his role becomes murderously oppressive. His intensity and inability to consider other possibilities is a good lesson to anyone who thinks their reading of scriptures is the only possible interpretation. Latch onto that, evangelicals.

Still, the film has problems. Like the ark on the worldwide ocean, the plot heaves and tosses, sometimes losing forward momentum. Aronofsky tries to intertwine both evolution and creationism, which didn’t quite work for me. And any semi-literal take on this story butts up against the fact that the survival of the species is based on inbreeding. Aronofsky offers no answer for that one. While Connelly has a great, heartrending moment with Crowe in the third act, as you’d expect in a biblical tale, her character—and all of the women in the piece—lack much agency.

But the scale of this thing, the psychedelic vision of the director splayed across a massive canvas, is something to see. And Aronofsky’s gift for melodrama, used with powerful effect in Black Swan, is in evidence here as well. For those few who found The Fountain transformative, they’ll see for a change what a real budget can bring to Aronofsky’s distinctive storytelling ambition. This is big, and sometimes moving, filmmaking. And it’s no less weird than his earlier work, for all the megabucks.