Directed by Brian Percival

Written by Michael Petroni, from the novel by Markus Zusak

The Book Thief is a movie I’d like to slam unreservedly, because it takes what could be a genuinely moving story of people surviving through the horrors of World War II and instead frequently delivers material of maudlin schmaltz. But I can’t condemn it entirely, because in the places it does work—in a couple of key performances and in its production design—and, in fleeting moments, manages to be quite affecting.

Let’s start with the good before going on to the bad.

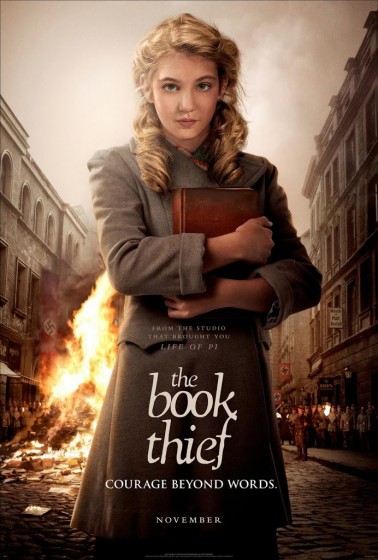

Germany: 1938: Liesel (luminous 13-year-old Quebec actor Sophie Nélisse) is abandoned by her mother, a Communist, and is taken in by an older couple in a small town. The couple, Hans (Geoffrey Rush) and Rosa (Emily Watson) are kind people—well, she’s curmudgeonly, while he’s a sweet accordion player. Liesel can’t read, and is teased about it in school, but with the help of Hans, quickly takes to books. She also finds a friend in neighbour kid, Rudy (Nico Liersch). On the run, a young Jewish man, Max (Ben Schnetzer), shows up at their door, seeking asylum. They hide Max from the townsfolk as the grim reality of war intrudes on their lives.

The cast is pretty great. At the centre is Nélisse, who is in almost every scene and is expected to deliver dialogue in a thick, sometimes cartoonish German accent. Her large, expressive eyes carry much of the film’s drama, and her performance is worth the price of admission. Also, Rush and Watson are such pros, especially Rush. The rascal exudes a baked-in warmth.

I also liked how the film is set up from the start as a bit of an alternate reality—the lovely location cinematography (the helicopter shots of a train in the snow are particularly impressive) and the soft glow of seasonal change feels like a fairy tale. Oh, and Death is the narrator. I’m not saying that having The Voice of Death pipe up from time to time works in the film—it’s a literary conceit that should have been dropped as it reminds me of Monty Python. But I do see that what we’re getting isn’t a historical document, that this story dealing with elements of the Holocaust and the privations of war has a softened perspective, as if it’s a Christmas movie in disguise, where even the Grim Reaper has feelings of compassion. There are no shades of grey here, no moral equivocations, just evil Nazis and kindly Germans. As a result, the film would probably appeal mostly to a younger audience.

So, those are things I enjoyed. Unfortunately, there was much I didn’t, most crucially moments where the sweetness crosses over into teeth-aching wrongness. A death scene is particularly badly handled, and, late in the running, a key reunion of characters doesn’t offer much emotional impact.

It also lags badly in the middle—where plot details (such as one character’s selection to be part of a Hitler Youth program) are just left dangling. Some deft editing would have provided a lot more narrative propulsion, and maybe we could have lost a pointless moment where children wander to a lake and scream about how much they hate Hitler.

This is also a film that utilizes a few hoary techniques to let us know everyone is speaking German, utilizing German phrases such as “nein” and “dummkopf.” I gather these expressions peppered the book this film is based on, but that kind of loyalty to the text, as with Death telling tales, doesn’t really work for the movie.

It’s almost as if the filmmakers wanted to make a production in the style of films from the era The Book Thief is set, with those same conventions updated slightly for a modern audience. But as Steven Soderbergh discovered when he tried to do a similar thing—aiming for a George Cukor-esque picture with The Good German—you really can’t go home again.