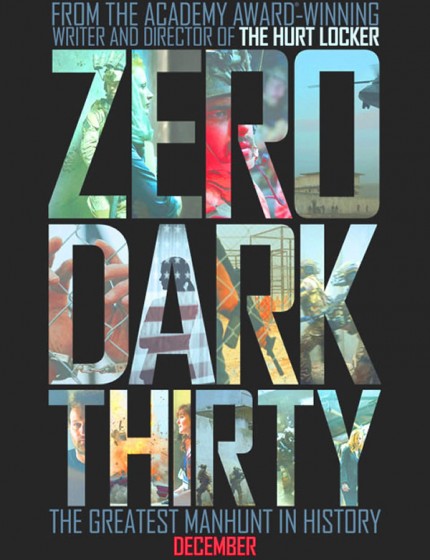

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

Written by Mark Boal

In the opening scenes of Zero Dark Thirty, following the text that the film is “based on first-hand accounts of actual events,” Jason Clarke’s CIA agent, the single-named Dan, is interrogating a prisoner at some Black Site, an American ops location without an address, somewhere in Pakistan. They’re discussing information. There’s a lot of hostility as the detainee has been standing, roped by his wrists, in a dirty room, for who knows how many hours. One calls the other a “garbage man,” the other retorts with “paperboy.”

It made me think of Apocalypse Now. One of Col. Kurtz’s (Marlon Brando) rambles, “You’re an errand boy, sent by grocery clerks, to collect a bill.”

Is this to be a Conrad-esque trip into the Heart of Darkness, an assassin sent to end the life of the man at the end of the river? I don’t think the comparison is so far-fetched. Nor is one with Silence of the Lambs, where a qualified young woman sticks to her instincts to track a killer in a world full of violent men, the final scenes a wash of night-vision green lenses and muzzle-flashes.

But, in most ways, Zero Dark Thirty is a more dangerous proposition as cinema than either of them, having inflamed American conservatives for access the filmmakers may have had to the White House and classified materials, and outraged progressives by telling a story that may be giving tacit endorsement that not only was torture employed by the American forces, it actually worked to help nab bin Laden. They’re calling it reprehensible, making heroes of characters who operated with impunity outside international law, saying this kind of irresponsible storytelling has an impact on American public opinion of such practices.

For me, that outrage seems naive. The fact of Guantanamo Bay’s existence and operation since 9/11 is evidence enough that America has needed a place where the CIA and the military could get away with behaviour that they’d be prosecuted for on home soil. And for the people working in these worlds, don’t the ends always justify the means? I guess I’ve always just assumed that kind of thing has gone on. Am I cynical or realistic? Discuss amongst yourselves.

I’m also reminded of the Israeli hawks who were pissed off at Munich, in how it showed Mossad assassins might have had a conscience that complicated their work. Not much chance of that here. That’s not to slight the Spielberg film, which I think is excellent, but I think there is room for different stories. I believed the people who hunted Osama bin Laden felt they had an important job to do and did it to the best of their ability. And I believe a lot of what we see in this film is standard operating procedure. Are the filmmakers turning the American operatives into heroes? I didn’t get that. In one scene, when Barack Obama says on TV the American government is anti-torture, the agents watching just look blankly. They barely acknowledge what they’re hearing. Business as usual. Dirty job.

Really good at her job is Maya—also only one name, played by the versatile Jessica Chastain. We meet her shortly after 9/11 when she’s sent to help the operation to track Public Enemy #1. The torture scenes are unpleasant, and served right up front they force the audience to make a call from the very beginning: this is the world in which we’re living. From there the story becomes very much a procedural, with other characters coming and going was we jump through the years, chasing leads in Pakistan, Afghanistan, The UK and Washington. Jennifer Ehle as Jessica, another longtime CIA operative, is excellent, as is the aforementioned Clarke. Later on we get some great scenes with a bewigged Mark Strong, Mark Duplass—who’s had an excellent 2012, with his work here, in Safety Not Guaranteed and Your Sister’s Sister—Stephen Dillane, Joel Edgerton, Kyle Chandler and James Gandolfini as the unnamed CIA director. But Chastain is the chilly heart in the centre of this story, who gets tougher as she goes along, applying her will to the people around her in order to get things done.

Structurally, we know where it ends, but as it gets close to that night in May 2011, and we see the longshot hunches that are pursued in order to find the quarry, the film gets more gripping from moment to moment. I found one telegraphed scene of suspense in the second act to be a disappointment—you can see what’s coming a mile off, even as the characters can’t, which puts the audience in a position where they are a step ahead of the investigators, a place we shouldn’t be at any point in the film until the final minutes.

For me, the arc of emotion, from nausea to an almost numb sense of satisfaction when we reach the inevitable conclusion, doesn’t necessarily provide the usual “thrills” one might expect from this kind of movie. You’re not going to get to know anyone very well; they don’t have alter egos. Maya is her job, and not much else.

So, I don’t think there is an endorsement of torture going on here, any more than there is an endorsement of drone strikes on targets in Pakistan and Afghanistan, or any of the other things the US does on any particular day in the region in order to protect their interests. I think what’s going on here is docudrama. The fact that both sides of the political fence are up in arms about it feels to me like Boal and Bigelow got a lot of details right.

And it makes Zero Dark Thirty the most essential feature film of the season. See it and have an opinion.