This essay is dedicated to Gregory Hatt Jr. for his birthday.

People are starting to conclude there can only be two Terminator movies and it all comes down to theme.

James Cameron is arguably one of the most culturally impactful “pop-culture auteurs,” but he’s often been ridiculed for his use of metaphor. His last movie, Avatar, was mocked for being too iconographic, explicitly borrowing from Pocahontas, “chosen one” narratives, and all the rest. And yet, Avatar made a ton of money. It also reframed mainstream discussions about international resource development, post-colonialism, and ecological conservation, much in the same way Terminator reframed the discourse around technological development and artificial intelligence. Like Michael Crichton, Cameron’s themes become our themes.

1984

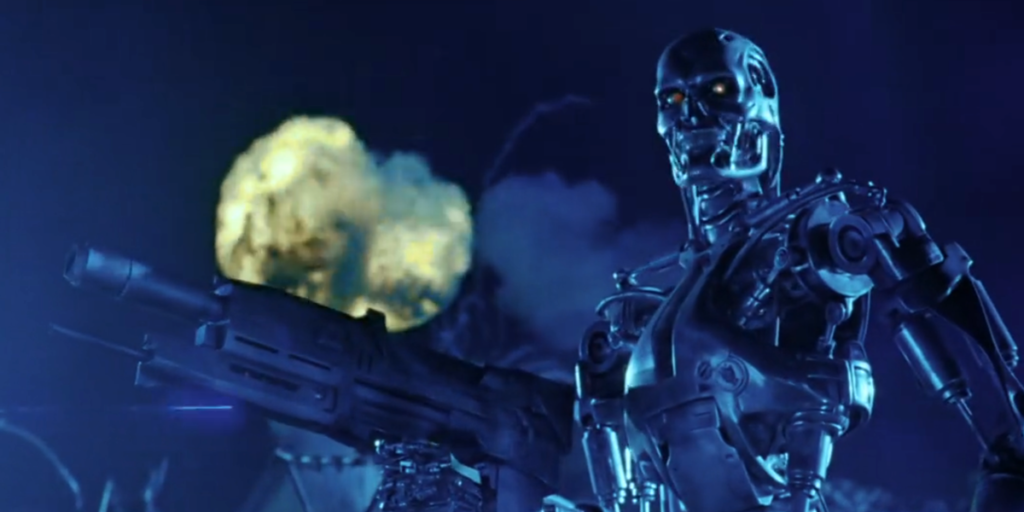

The Terminator updated the Frankenstein narrative by placing it in the context of the nuclearized and computerized Cold War. The genre elements, like the nuclear arms race, future wars, time-travel, self-conscious machines, and all the rest, were already well known. In Cameron’s hands though, they snapped with electricity.

In The Terminator, humanity is faced with annihilation because of its own creative and self-destructive tendencies. In order for humanity to survive this tendency, “good people” must remind humanity how to resist giving up.

In our time, we watched “Hope” become a political slogan and then we watched the backlash against it.

1991

“We’re not going to make it, are we? People, I mean”, a young John Conner asks, watching children play-fighting with guns. The terminator replies: “It’s in your nature to destroy yourselves.”

Terminator 2 (T2) was a perfect sequel in many ways and Cameron was always a master sequel maker. He inverted the characterisation, swapping the villain for a hero role, and raised the stakes by introducing a stronger antagonist and more vulnerable “asset.” Most importantly, he introduced a possible way out of humanity’s “dark fate.” These alterations become the glue trap in which later sequels get stuck. They chew their own legs off but still can’t escape.

Thematic Closure

T2 worked because it developed and completed the intellectual and emotional arc setup in the first film. In The Terminator, humanity must resist its self-destructive “works.” In T2, “there is no fate but what we make.” It’s a challenge to humanity: Do better, be better, and use our gifts to do more than just survive our future. And with that, the story is done.

Except it wasn’t, and there were more movies, and more, and more, as though it was Skynet itself sending endless Terminator sequels back in time.

So what happens to that satisfying thematic arc? It has to be subverted for the story to continue.

“Emotional Balls”

The first two Terminator films also work because of how they made us feel. James Cameron famously loves Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but he makes an interesting distinction in that admiration:

“It’s not a film that I like; it’s a film that I love… When I say I don’t like it, it’s that I don’t like the feel of the film. I don’t like its sterility. I like a film with a little more emotional balls, just as a movie, to get involved in. But as a work of art, I love [2001].”

It’s an interesting observation. The Terminator and Terminator 2 have emotional balls. The sequels are sterile like mules. They have trucksticles.

Movie Franchises

Trying to enjoy Terminator sequels after T2 has been like picking the bacon bits out of sad Caesar salads.

In the political economy of the filmmaking, firms are increasingly monopolized, having access to large treasuries of plundered properties. The more money invested in big tent pole movies, the more they need mass market appeal and certainty for a return on investment, thus creating “theme park rides,” to use Scorsese’s now famous image. But “appeal” is an initial reaction. “Love” comes from sustained contact.

The other lens to be considered is the online culture wars where various market audiences fight over the “true meaning” and “right direction” of blockbuster franchises. I personally don’t believe there is a monolithic “PC culture,” though there are growing PC and reactionary markets. For people who want to see better gender and race representation in lead casting and storytelling, Terminator: Dark Fate is a welcome treat. We missed Linda Hamilton, and why couldn’t a woman of colour save the world? Others think that representation ruined the movie. Accusations of “PC culture creep” are often made to scapegoat financial failures. It’s hard to replace nostalgic love.

“Legacyquels”

Like Dark Fate, The Force Awakens was rightly ridiculed for rehashing the beats of A New Hope, but we all know it wasn’t because of lazy writing. It was a marketing approach some call the “legacyquel”. A legacyquel must function as a sequel to a beloved property while also creating an opportunity to reboot a new franchise. Folks have pointed to Tron: Legacy as the paradigmatic example. These productions give old fans recognizable images and callbacks via pastiche while retelling the classic arc for new audiences.

The problem with Terminator sequels after T2 is that they’ve always been legacyquels. Like a drug dealer in a playground, each sequel tries to get us hooked on a new multi-film deal, and each time we turned them down.

Reset the time machine. Send another one through.

“Sequels”

In Philip K. Dick’s 1953 story “Second Variety,” the UN and Soviet Union have decimated the earth through perpetual war and nuclear conflict. In this new stage of the war, the UN unleashed a secret weapon; self-replicating killer drones called “claws,” programmed to kill Soviets. Diplomatic lines are reopened when it’s discovered that the claws are generating news models, unguided by human input or oversight, and they look like human beings.

The appearance of the titular second variety means that anyone could be a claw. Soon the war shifts and the now united humans struggle against their own killing machines. By the end, autonomous killing machines take over earth and start making weapons to fight each other.

The Terminator is a spiritual relative to “Second Variety,” in the same way The Thing and Alien are spiritual grandchildren to John W. Campbell Jr. 1938 novella Who Goes There?

Remakes and sequels aren’t always “problems.” The issue with Terminator movies is that they are imitations of movies. Rise of the Machines, Salvation, Genisys, and now Dark Fate have all the recognizable and enjoyable features, but their themes fall flat. They pretend to be Terminator movies just like terminators pretend to be human.

Why HBO’s Watchmen works and Terminator sequels don’t

Blade Runner 2049 is a great sequel. HBO’s Watchmen is also a great sequel. Both have a clear sense of what they’re about, and it’s not about aping the source material.

For instance, race was almost completely missing from the original Watchmen comic but this adaptation places it front and centre. It is important to ask what you’re adapting when you set out to resurrect source material from another time. The Watchmen show adapts a tone, a sociological lens for looking at America and why they worship “heroes.” It’s not really about capes and masks in themselves.

“Don’t you love Terminator?”

Terminator sequels pretend like nothing has changed since the early-1990s. In 2019, the Terminator’s iconography shambles like a zombie.

Deadpool director Tim Miller said they wrote the script of Dark Fate around the action set pieces and it shows. Christopher McQuarrie does the same thing with Mission Impossible movies and it works. Ask yourself what the difference is between those two franchises.

The later Terminator sequels cut the skin off a dead cat, wrap it around an empty coffee can, and post the photos on Instagram with the caption: “Hey, don’t you love cats?!”

Our Defeated Resistance

The real problem is that the future in Terminator doesn’t really make sense anymore. The stats seem to suggest that most people don’t really worry about nuclear war. Even though most people agree that climate change is the most pressing issue for humanity in our time those same people don’t want to do anything more or pay any extra to change that. Companies profit by giving us outlets for our anxieties through green campaigns and hopeful or empowering messaging, but most insurance companies are planning for climate change to happen–that it’s unlikely humanity will actually try to stop it. With autonomous machines, there are global companies against them, but the world’s largest militaries, like China, Russia, and the US, are all working autonomous weaponry anyway. Most people don’t really care about that either. Maybe we can’t make meaningful Terminator movies because we don’t actually believe the future exists. Maybe we don’t think we can stop the future threats against us.

Over the past thirty years we’ve watched the “futures” predicted in our science fiction movies come and go. On August 4, 1997 Skynet doesn’t come online. In 2001, we don’t have a base on the moon or achieve our next evolutionary level. In 2019, we don’t have replicants or flying cars. The future never seems to come on time or at all. Can a Terminator movie mean anything emotionally when you think of the future the way we do?

I’m not even sure the machines would have to rise up. If they asked for the world, we’d probably just give it to them as long as they promised to stop sending back all those Terminator sequels. Hell, we might give it to them for a free subscription to Disney+.

Don’t miss what Carsten Knox had to say about Terminator: Dark Fate and the rest of the Terminator franchise, on Flaw in the Iris.