My passion for movies comes from childhood. I watched a lot of movies with my parents, who didn’t do much to shield me from all those grown-up movies of the 1970s they liked to watch. Ratings to protect innocent, impressionable kids from the very adult themes of American cinema at the time wasn’t much of a concern to them, and I thank them for it because those movies helped me dissect what adult life might be like. They also made me love movies. I saw The Poseidon Adventure, Klute, The Omen, An Unmarried Woman, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Eyes of Laura Mars all before I turned 10.

I also saw a lot of Clint Eastwood movies. He was one of my father’s favourite actors and he was prolific as a director and star, so there was plenty to choose from once we got a VCR. By the time I went into junior high I was familiar with The Man With No Name trilogy, Two Mules for Sister Sara, The Beguiled, Where Eagles Dare, Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, The Enforcer, The Eiger Sanction, High Plains Drifter, The Gauntlet and The Outlaw Josey Wales . Liked them all, especially that last one.

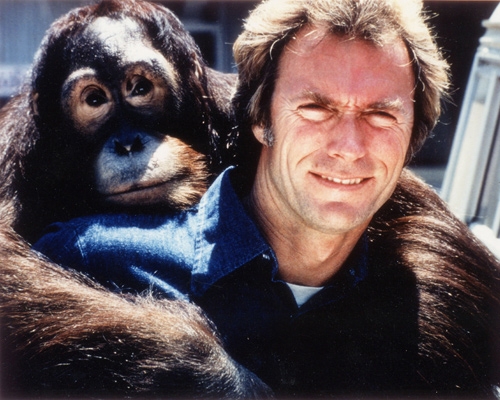

Eastwood was a big influence on my young life. He could deal with any problem, it seemed. I hoped I’d grow up and become him. (That, unfortunately, hasn’t happened.) I’d try and cultivate his grimace. Chose my words carefully, not say too much. When I got into fights with other boys, as most boys do, I’d ask myself, What Would Clint Do?

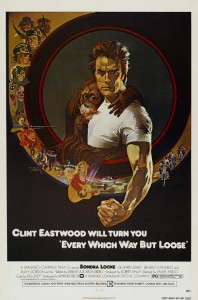

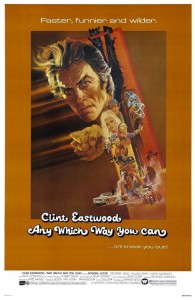

In the past week I revisited two of the Clint Eastwood movies I really enjoyed when I was a kid, but hadn’t seen in more than 30 years: Every Which Way But Loose (1978) and its sequel, Any Which Way You Can (1980). These pictures are pretty much forgotten, despite the fact that they were huge international hits. According to the IMDB, Every Which Way But Loose was #12 at the US box office in 1978. Any Which Way You Can was #5 two years later.

I guess you could call them “redneck action comedies,” a genre with little lasting cultural credibility. Maybe some of the oeuvre of Johnny Knoxville might qualify.

I gather the script for Every Which Way But Loose, by Jeremy Joe Kronsberg, was originally intended for Burt Reynolds. If there was a king of the redneck action comedy, it was him, though he might balk at the pigeon-hole. It’s hard to deny that movies like White Lightning, Gator, Smokey And The Bandit and Hooper were of a particular style. Lots of cars, lots of good ol’ boys, lots of fighting and lots of country music on the soundtrack.

Which ever way you look at it, there was a huge audience once upon a time. And Eastwood and Reynolds were two of the biggest stars in the world.

Every Which Way You Can follows the exploits of the unusually monikered Philo Beddoe (Eastwood), a 40-somethingtruck driver making most of his living in illegal, bare-knuckle boxing matches. Eastwood easily clears 6 feet, so he tends to tower over people, but when you think of the muscle-bound ‘roid ragers in today’s action movies, it’s a bit hard to believe this lean, granite-jawed dude was the baddest fighter in the west. But what Eastwood effortlessly conveys is toughness. And it was a broad comedy, after all—his best buddy is an orangutan named Clyde.

Beddoe lives in a shack behind a house belonging to his mother (the wonderfully cranky Ruth Gordon), shared with his trucker-cap-wearin’ buddy, Orville (character actor MVP Geoffrey Lewis) and Clyde, who likes to crap all over the place.

These movies very much hinge on the star power of the lead. Audiences better want to hang out with Eastwood because there’s not much else going on. By the late ’70s, Eastwood was iconic like an Easter Island statue, so he could get away with being in movies with, at their bedrock, a lazy kind of storytelling.

It starts with Beddoe fighting a guy, knocking him out and making a bunch of cash. He goes to a country and western bar called The Palomino, meets a country singer from Colorado named Lynn Halsey-Taylor (frequent Eastwood collaborator Sondra Locke).

Beddoe pisses off a couple of cops and a biker gang called The Black Widows, led by a dude named Cholla, played by another Eastwood regular, John Quade.

A lot of time is spent with Beddoe and Clyde in a piece-of-shit pick-up truck driving around the grungier neighborhoods of Los Angeles. It’s definitely LA, but there’s no real effort to try and identify it. It’s just generic America-town.

After Beddoe and Halsey-Taylor get amorous, she vanishes from her trailer-park digs (natch’) with a guy. Beddoe isn’t one to give up, so hops in the truck with his buddy and his primate and off they go after her, with the disgruntled cops and the biker gang in hot pursuit. I enjoyed the moment when Orville picks up Beverley D’Angelo at a vegetable stand on the highway. Her name is Echo, and every time she introduces herself she has to say her name twice. I think it’s meant to be a joke.

Eastwood had subtly satirized his western image in The Outlaw Josey Wales; here he goes an extra mile, clearly comfortable appearing in a standoff with the bikers on a muddy street corner as we hear the telltale Ennio Morricone whistle from The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

I’ll tell you about the one scene in Every Which Way But Loose that lifts the film off its belly for a minute. Beddoe has been hearing throughout the film’s running time about this legendary fighter, Tank Murdock (Walter Barnes). And when he finally faces Murdock, who is out of shape and not a young man, Beddoe gets the advantage and is going to finish him off, thereby disappointing Murdock’s gathered fans. Beddoe has a moment of compassion and takes a fall to allow his opponent’s victory. It’s not explained why he does this—he and Murdock don’t have any previous connection. Maybe he just sees someone who needed the win more than he did. Whatever the reason, it’s a nice moment.

Compared to the first film, the sequel, Any Which Way You Can, feels a lot more polished. Part of that is the style longtime stunt coordinator first-time director Buddy Van Horn brings to the party. He worked stunts on the previous film, so it makes some sense he’d be brought in to helm this one, given all the set-pieces. But it wouldn’t be hard to imagine that Eastwood called action on a lot of shots.

The sequel brings almost the entire cast of the first one back together, and gives Clyde a lot more screen time. The first film had made him a star but—big revelation here—I have it on good authority they got a different orangutan to play Clyde in the sequel. Hollywood, man. No loyalty in that town.

I really love the opening helicopter shots of these two movies, basically coming out of the sky to focus on Beddoe’s truck driving down a massive freeway. This was a popular technique of the era (see Burt Reynolds’ Sharkey’s Machine for a similar thing) and I think it connects the audience to the characters and to a shared car culture, as well as it being a great equalizer: This could be a story about any of us. If we had, you know, an orangutan.

Halsey-Taylor comes back to town and makes up with Beddoe, who quite rapidly forgives her for her con-artist transgressions of the first movie. The Black Widow biker gang, in all their unthreatening glory, are out for revenge, of course, and a new element is a New York businessman with a gambling sideline looking to arrange a fight between Beddoe and his own bare-knuckle brawler, the awesome William Smith.

Smith terrified me as Falconetti in the Rich Man Poor Man series, more 1970s entertainment was exposed to despite it being probably too mature for my pre-teen brain. (Check out the career this guy has had. He’s still working at 80.) And he’s great here.

He’s not really the bad guy—his Wilson is an unlikely match for Beddoe. And the climax in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where they fight through the streets in front of an audience of whooping gamblers is a blast.

But the highlight of the film, if you can call it that, is a central sequence where four couples get it on in a Bakersfield motel, including Clyde and his sweetheart from the zoo. It includes a scene of Ruth Gordon’s face superimposed on Bo Derek’s body. Beyond that it’s pretty much indescribable.

So, that’s all I have to say on these movies. They still have the power to charm, and I don’t think it was entirely nostalgia.

I remain, not Clint Eastwood.

A Cult of One is an semi-regular feature on Flaw In The Iris where I shine a light on movies that I think deserve a little more love than they’re currently receiving in the culture. At the very least, they shouldn’t be forgotten. For other entries, please click on these titles: Tequila Sunrise, The Russia House and Impromptu.