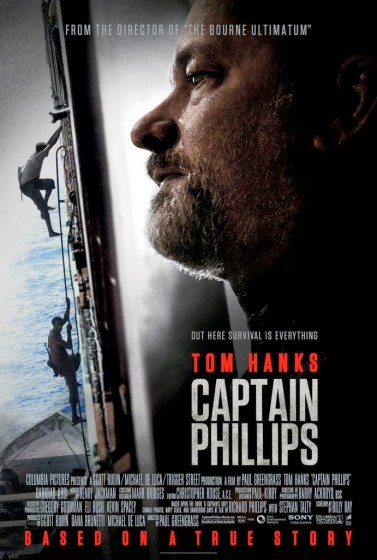

Directed by Paul Greengrass

Written by Billy Ray, based on the book A Captain’s Duty: Somali Pirates, Navy SEALS, and Dangerous Days at Sea by Richard Phillips and Stephan Talty

Greengrass is the king of docu-dramatic liberal action cinema. I realize that’s a bit of a mouthful, and that if I’m right about the association, the UK filmmaker would be the single practitioner in this sub-sub-genre. He owns it. There’s something in the combination of jagged editing—which Greengrass accomplishes here and typically on his films with Christopher Rouse—kinetic, hand-held camera, and a substrata of driving score supporting socio-political material that make his films unlike all others coming out of Hollywood right now. And it’s funny, because though he’s best known for spy movies The Bourne Supremacy and The Bourne Ultimatum, it’s in his other prominent features, Bloody Sunday, United 93, Green Zone and now Captain Phillips, all dramas spun from real life events, where he really manifests this thematic continuity.

This one is based on the 2009 hijacking of the international freighter Maersk Alabama, sailing from Oman to Kenya around the horn of Africa. Though there’s some controversy over Phillips’ account of what happened and the intentional danger he may have put his crew in, I understand the film more or less cleaves to the book’s tale.

And as a thriller, I found it to be competent, engaging, and yes, in places, thrilling. But I think what makes the film of real interest is in its geopolitical commentary, which is informed by Greengrass’ own political bent. As the picture reached its conclusion, I really started to feel more and more sympathy for the antagonists, malnourished Africans totally out of their depth, eking out whatever living they can by interrupting international commerce and facing down the world’s greatest military force. Though I wouldn’t be surprised if American conservatives rallied around the film because, on its face, it celebrates that gung-ho war-machine efficiency, I don’t believe that’s what Greengrass is doing. The imagery clearly shows the enormous inequity of power.

We start with Phillips (Tom Hanks) in his Vermont home, reviewing his agenda as ship’s captain. As he and his wife (a barely in it Catherine Keener) drive to the airport, they speak in some of the most stilted and expositional dialogue I’ve heard in awhile. They actually refer to their children as “the kids” as they discuss the future and how they have fewer opportunities. That exchange is juxtaposed with a conversation that takes place on a beach in Somalia. A group of men assemble to join two teams of pirates, pressured on pain of death by their warlord bosses to go get a freighter. These are competitive, desperate, hollow-ckeeked men who don’t eat anything but khat, the stimulant shrub. They clearly don’t have any other option for their day—they claim to have once been fishers whose livelihood collapsed when the sea was emptied of catch by industrial fishing. If they aren’t pirates, what else would they do?

Phillips comes across as a tough taskmaster of his crew of 20, but he’s a man who is serious about his job. His concerns over security prove prophetic as the pirates chase and eventually catch the giant ship, boarding it and threatening the crew. And it’s not long before the US Navy shows up.

Greengrass constantly contrasts the scale of these ships, both the commercial and the military, with the boats the pirates use. The pirates are dwarfed. When you think about it, it’s actually kind of amazing they have any success at all. And while the pirates—all Somali actors; Barkhad Abdirahman, Faysal Ahmed, Mahat M. Ali, and Barkhad Abdi as Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse, the leader—come off as violent and aggressive, they’re never cartoons. Abdi makes Muse especially thoughtful and interesting. His countrymen call him “Skinny Rat,” but he’s resourceful and very, very tough, as he is constantly required to prove in an environment of masculine power and competition. And as his situation becomes more and more dire, his quiet resignation—”I’ve come too far to stop now,” he says—becomes touching and tragic.

I don’t think I need to say how good Hanks is in his role. While much of the third act is occupied by extreme close-ups of his perspiring face, his natural likability is undiminished by experience, and when he has a moment to show some unguarded emotion, it’s a tidal wave.

In the end, no one will be surprised that Phillips is saved—he co-wrote the book, after all, and his name is the dumbly obvious title of the movie. And, yes, we do witness the astonishing efficacy of the US military—it’s both awesome and terrible to see. But there is no way Greengrass is celebrating this show of force, considering what its fighting against. The enemy are four, untrained starving guys in outboard-motor powered skiffs carrying AK-47s. And they may have given this unlucky sea captain a bad time of it, but I think what Greengrass is showing us—inside this effective thriller package—is what the world looks like in its most difficult corners, and how little power most of us have in our lives. We all have to survive, we all have to serve somebody.

How different would we be in their situation? Not at all, I think.