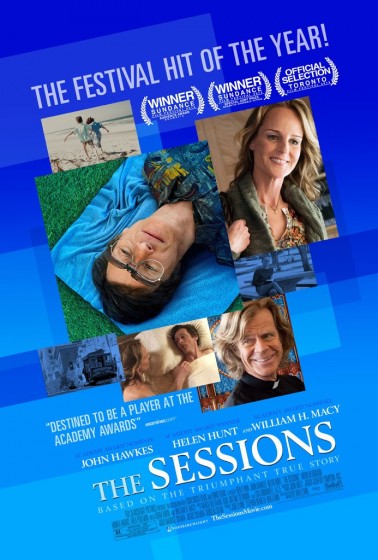

Written and directed by Ben Lewin, based on

an article written by Mark O’Brien in The Sun magazine

A drama giving us a look into the lives of people who we don’t see often on the big screen—the disabled—the tale told in The Sessions (when shooting it was entitled The Surrogate, but I suspect they changed that due to its pregnancy connotations) is about Mark O’Brien, a journalist and poet. Confined to a gurney due to having contracted polio as a child, he says, “I’m not really paralyzed, my muscles just don’t work.”

Having managed a fairly self-sufficient life, as much as he can—he graduates from university, earns a living, but still spends most of his time in an iron lung—he has reached his late 30s having missed out on one of life’s undeniable pleasures: sex. It’s a journey of understanding that starts when he writes a piece about disabled people who have active, nay, vigourous, sex lives. He starts to understand what he might be capable of, while still terrified. “I feel like an anthropologist studying head-hunters,” he says.

John Hawkes, so good in Winter’s Bone and Deadwood, seems to be using his voice differently here, playing Mark O’Brien. It’s in a higher register, making him sound younger than he appears, and perhaps more vulnerable. He’s enormously expressive while at the same time effectively communicating serious physical limitations. It’s a great performance, and must have been very difficult to maintain his prone position. It’s a cliche, that Academy voters reward performances where actors play someone who is disabled, but this is something else. It would be a real snub if he doesn’t get recognized.

First seeking counsel from his priest, Father Brendan (the incredibly likeable William H. Macy), Mark signs up with a sex surrogate. Though the movie is set mostly in the late 1980s, this still seems like a fairly forward-thinking idea: a sex surrogate is someone who helps people overcome their sex and intimacy hang-ups. The difference between a surrogate and a prostitute, as is explained in the movie, is that surrogate isn’t looking for regular business. There is a fixed limit to the sessions in question: Six.

The sex surrogate, Cheryl Cohen-Greene, is played by Helen Hunt. Since she won the Best Actress Academy Award in 1997 for As Good as it Gets, Hunt hasn’t shown up very regularly in feature films, it seems to me. She’s become choosey with her projects. More power to her, I say. She had to act opposite Paul Reiser in Mad About You for seven seasons. She’s paid her dues.

She’s also very good in the role, balancing a need to be professional with the feelings that can emerge when you share intimacies with someone. She’s a bit flinty, what with her razor-sharp jawline and slightly frowny demeanor, a trait that I think puts people off, but she says a great deal with her eyes. Interestingly, Cheryl has a husband (Adam Arkin), who is supportive of her career choice, to a point.

There’s a lot of nudity in The Sessions. Interestingly, Hunt goes the full monty, which given her age and the kind of pressure put on women in Hollywood to look perfect, is a gutsy move. I can well understand the reasons Natalie Portman gives for not being nude on screen—the images live forever on the internet—and I can understand why some female actors say their breasts upstage them. They say once you take off your top, your boobs are all people look at and they stop paying attention to what’s happening in the scene.

But, at the same time, I also hate how uncreative some filmmakers can be to cover women up. The L-shaped bed sheet, for example, popular in so many films, is a particularly egregious example.

But given the material, it would seem weird for Hunt to not to be nude, and I gotta say, it’s weird that Hawkes is spared having to show his tackle. I suspect that has to do with the double-standards in terms of movie ratings in the United States rather than his modesty; he shows most everything else.

What’s disarming about The Sessions is not only the down-to-earth frankness about sex, or the realism in the depiction of people with disabilities, it’s also got some interesting things to say about sexism and racism, too. And, it’s funny! Shockingly, even Catholicism comes out looking good, thanks to the even-handed kindness of the priest. All of this is done without a smidgen of sentiment or syrup. This quiet little movie is a hell of an achievement, all things considered.

(And great to see Rhea Perlman again, if only in a single scene.)