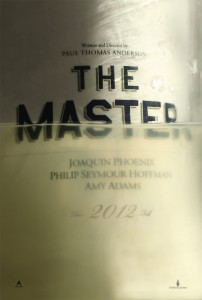

Written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

The release of a PT Anderson movie is an event, every single time. Every one since his first, Hard Eight; Boogie Nights, Magnolia, Punch Drunk Love and There Will Be Blood. With this collection, Anderson can stake a claim as the finest American filmmaker working today.

So, what to make of his newest offering?

Well, while it lacks none of the ambition of his previous work, for me it just didn’t quite hold together. The narrative is confident enough to let the audience piece together the many missing elements, to fill in the gaps around the film’s heart—the key relationship between two men, Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix). But as it reaches its final act, the sprawling, almost expressionist story frustratingly avoids a dramatic crescendo, despite some deftly crafted suspense and performances.

Dodd is the one they call The Master. Anderson has gone on record as saying the character and circumstances depicted in the film are based on the life of L. Ron Hubbard, founder of The Church of Scientology, though has been reluctant to connect the story with any current-day version of the controversial religion. It isn’t hard to believe that the beginnings of Scientology were very much like this: a group of people committed to The Cause, the book and teachings of a very charismatic, if troubled, man.

But we don’t start with this. We start with Quell, a frustrated, lonely World War II vet whose skill is in distilling. He makes cocktails out of paint thinner, rubbing alcohol and whatever the stuff is in bombs. His alcoholism and anger don’t serve him well as he struggles to hold down a job, picking fights with customers at a department store photo portrait studio and poisoning migrant workers with his moonshine. When Quell falls in with Dodd and his followers, there is a strange kinship. Though Quell is single-minded and unsophisticated, Dodd recognizes something in him, like Quell is an earlier, less evolved version of Dodd. Dodd speaks of animals, that humans don’t have to be like them, but we get to see in a few, brief moments, how Dodd’s anger is only just beneath his intellectual veneer.

Like Robert Altman’s MASH, set in the Korean War but really about Vietnam, a story about a veteran struggling with his life after WWII seems to me to be really about Iraq and Afghanistan, about those men and women who return from the theatre of combat changed by what they’ve experienced, desperately looking for something to give their lives meaning. Quell can’t admit it to himself, but that seems to be his impulse.

Quell becomes the subject of Dodds personality experiments, pushing him with intense questioning and repetitious, humiliating tasks. We occasionally are reminded we’re seeing events through Quell’s eyes, when he imagines all the women in a room naked, or when he’s told to see eye-colour change, he does. We do. But I don’t get the impression that Quell, even with his violent outbursts and unpredictable behaviour, is an unreliable narrator. We are on his journey, and we care about him. We believe him.

Hoffman and Phoenix both give gigantic performances here. Like the spiritual, bastard children of Marlon Brando, Hoffman’s Dodd channels some of Vito Corleone and Colonel Kurtz, while Phoenix brings a touch of Terry Malloy or Johnny Strabler. Phoenix is especially physical in his role: the hunched shoulders, the lisp and the hands on hips, thumbs forward and elbows out. But nothing feels forced. There’s no doubt he’s compelling, handsome even, as his inner twists manifest in these exterior ways, constantly reminding you of his coiled, dangerous aspect. The best part of The Master is the playfulness here between the actors; their scenes together are a joy and make the core of the film.

But with the exception of a couple of big blowouts—a scene where the two men spend time in jail in Philadelphia and then, later, when Dodd’s instructions of Quell seem to bear fruit—we have a lot of dramatically low-key scenes where not much happens. It’s a patchwork of moments, of scenes, that misses a forward momentum. Amy Adams really suffers in this: her character’s job seems to be to direct/satisfy Dodd and be pregnant so we can measure the passage of time through her expanding midsection. But her character and performance is overshadowed by the monsters around her, the way Daniel Day Lewis’s epic character Daniel Plainview blocked out Paul Dano in There Will Be Blood.

And there’s the main comparison I think it’s important to make. With Plainview, there was a definite arc for the character and us. At the end of the film, we’re all wrung out by the journey, but we’ve definitely been taken somewhere. I don’t know where The Master takes me, if anywhere, really. It suffers from a biopic trope even though it’s fictionalized: real life can lack some punch. At least Hoffman and Phoenix have plenty.