Welcome back to this irregular feature on Flaw In The Iris, where I revisit an unheralded or underloved movie in my vault. I’m hoping to explain why the film works and why it deserves a fanbase. I’m also willing to accept I may be the only person to really appreciate the film in question… feel free to tell me if so.

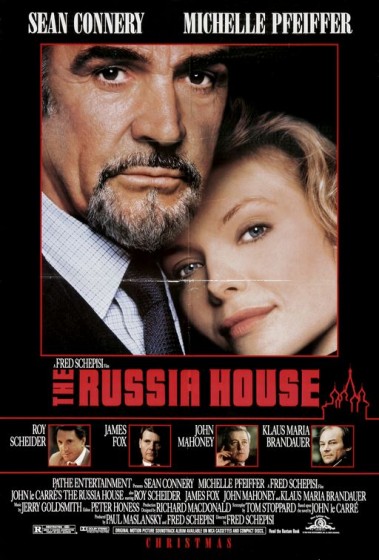

The Russia House (1990)

Directed by Fred Schepisi

Written by Tom Stoppard, from the John le Carré novel

The Russia House is a great movie to watch when you’re feeling heartbroken, and I’ll tell you why.

It has great and beautifully-shot locations—rainy London, sunny Lisbon, autumnal Moscow and St. Petersburg and even British Columbia, standing in for (probably) Switzerland. It fills your mind with visions of exotic and faraway places.

It’s an adaptation of a John le Carré novel so you know its espionage elements will be twisty and clever, put together by the inestimable Tom Stoppard, who, for my money, is one of the great screenwriters, especially in how he adapts from the page. It will engage your brain.

And it has, at its centre, a very unlikely romance, between a middle-aged man self-described as “an unmade bed with a plastic bag attached” and a beautiful Russian woman. It gives hope to all us awkward types if such a thing can happen.

That those two parts are played by Sean Connery, whose James Bond history will follow him forever, and the icy-cool Michelle Pfeiffer, gives the entire affair the air of classic Hollywood that makes it feel just a little more glamorous than real life could ever quite manage. Top that off with a nostalgic orchestral score from Jerry Goldsmith, including great dollops of Branford Marsalis’ gorgeous sax. The effect is a bit hypnotic, which is just what an aching heart needs.

The story goes like this: “Boozy” Barley Blair (Connery) is a British small press publisher sent a package from a Russian woman named Katya (Pfeiffer). But he doesn’t know a Katya. “Never slept with one, never even married one,” he tells the British Secret Service—including James Fox as Ned and director Ken Russell[!] as Walter—and the CIA—including JT Walsh and John Mahoney, with Roy Scheider’s Russell in charge. The package contains documents that indicate the Soviet nuclear defensive package is badly out of date. Don’t forget, this is the tail end of the cold war. Even after the wall fell, things were pretty chilly.

Now, if only they could make sure the documents are real. (And if they are, who’s going to “sell that story on the hill?” So much money in American contracts are tied up in the idea that the Russians have big guns and could use them at any time.)

Half-heartedly, they press Barley into service, sending him to Moscow to interview Katya and find out if the docs are legit. Turns out they are, penned by Soviet nuclear scientist Dante (Klaus Maria Brandauer), Katya’s ex who Barley met once at an artist’s retreat outside Moscow. But the Sovs have figured out his game and Barley and Katya’s lives are suddenly in a lot of danger.

The script not once, but twice backtracks into the story, filling in the gaps from different character perspectives without being too precious or too clumsy about it. Given the complex needs of the plot and the suspense, it’s a testament to Schepisi’s control and Stoppard’s gifts with words that it all holds together so well, aided by shooting in those gorgeous locations.

I don’t know if Connery and Pfeiffer have immediate chemistry, but they are so engaged in their roles, even if I don’t entirely believe them as lovers I do believe them as people. Pfeiffer’s accent is solid and Connery convinces a canny, high-functioning alcoholic with a few teeth still in his head.

The dialogue comes back to me all the time, especially “Honour is due, Ned!” It’s funny, hearing the spies talk about honour, when they have so little of it. If you want to dig into this material, I think that’s what it’s really about. In order to do the right thing, in order to be decent, we all may have to be traitors to our nations. The war machine feeds only itself.

And that’s the final reason I watch it when I’m a sad. Because The Russia House shows how individual effort can change the dynamic between nations, bringing a measure of peace. It’s enormously optimistic in the face of unfeeling bureaucracy and cynicism. That’s something we all should be able to relate to.