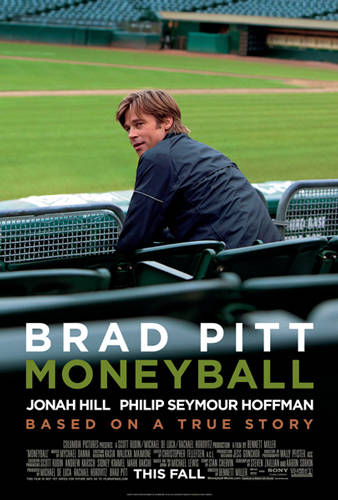

Directed by Bennett Miller | Written by Steven Zaillian, Aaron Sorkin, from a Stan Chervin story, adapted from a book by Michael Lewis | on Netflix

The first thing Moneyball taught me is that those armchair loudmouths who call into sports shows are a bunch of know-nothing douchebags. Yeah, that’s right. Sports radio is full of these guys, both the ones that are paid to be on air and the ones who like to make the calls from their couches with their thumbs up their asses and the station number on speed-dial. Those guys don’t know shit.

The second thing the movie taught me is that even the guys who work for the teams, the scouts and advisors, most of those guys don’t really know shit, either. The debunking of the pro-sport myths is what this movie does better than anything.

For those of you who aren’t enamored with the sports movie, this one brushes against the genre, but really it’s about human nature. In that it’s more like Scorcese’s The Color of Money than, say, The Natural or Eight Men Out. That said, it’s mighty fine.

It tells the true story of the 2002 Oakland Athletics. The year before they’d gone to the American League Division Series and lost to The Yankees. Then, in the off season, they lost their three star athletes to free agency trades. They were gutted, and dealing with a third of the budget, say, their New York nemeses had to play with.

General Manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt, looking more like Robert Redford than ever)—once a pro player himself who despite being a hot prospect in his youth didn’t set the league on fire—is inspired by a 25-year-old Yale-educated economist and stats expert Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), who says the best approach is to choose new players only by their statistics. If they have a great percentage for getting on base, that’s all that matters. It didn’t matter that David Justice (Stephen Bishop) was 37 (ancient in baseball), he was a bargain and still got on base all the time. Same with Scott Hatteberg (Chris Pratt) who moved from catcher to first base. None of it made sense except in theory, except in the numbers.

Beane and Brand’s new approach makes them no friends in the clubhouse or the back office. A scout mutinies. Manager Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman, setting phasers for seethe) is frustrated by the office’s lack of faith in him, as represented by his one-year contract. And he sure hates the way Beane is micromanaging the new players. And for awhile it doesn’t work. But then it does. To a degree.

I won’t tell you what happens. I didn’t remember the MLB results in 2002, and I’m glad I didn’t because it made the movie that much more suspenseful.

And the system? It makes all kinds of sense. There’s no professional sport more consumed with statistics than baseball, why wouldn’t you try and and solve problems by consulting those stats and making decisions based on them, rather than on some kind of arcane alchemy or intuition? There’s a great scene late in the running when Beane—who never watches the game as he’d rather be working out or driving, listening on a radio from time to time—heads back to the ballpark because the A’s have a chance to break a long standing record. As soon as he walks into the stadium the team starts to mess up. It’s a wonderful moment where all the statistical analysis in the world can’t withstand a dose of irrational fear. And, let’s face it, past all of baseball’s towering stats lies the bog of superstition.

As with most of the scripts Aaron Sorkin has had a hand in, Moneyball makes you feel smarter just by watching it. It’s very clever in how it presents the stats (lots of close-ups of numbers flying by, lots of charts) and in Pitt’s character offers someone who’s ambitious, confident but flawed, a divorced father trying to serve as a good example for his 12-year-old daughter while still reaching for a success denied him when he was a player.

It’s not a perfect movie. I’d have liked to see more between Beane and Howe, especially after things started to change for the better. I’d have liked more with Beane and his daughter, to flesh out their relationship, to soften him a bit. Same with Brand, who doesn’t get to have much of a character outside his work. And Bennett Miller, brought in after Steven Soderbergh was let go (and what happened there, I wonder), doesn’t quite deliver the scope of the game on the field.

But overall, this is a winner. A solo homer into deep right. Look for it to be considered come awards season.