Directed by Derek Cianfrance

Written by Cianfrance, Cami Delavigne and Joey Curtis

Dean and Cindy are married. They live in small town Pennsylvania somewhere. Dean’s a house painter and Cindy a nurse. They have a daughter, Frankie, and their life is all golden-dappled and domestic. When the dog goes missing, you see the first signs of cracks in the bliss. Dean blames Cindy for leaving the gate unlocked, Cindy is impatient with Dean acting like a child. Maybe it’s just part of their regular life, maybe it’s something more.

We flash back to before Dean and Cindy met, years before, with Dean a handsome fella with a full head of hair, getting a job as a mover. Cindy takes care of her ailing grandmother and goes out with an obnoxious jock. Dean and Cindy meet by chance.

Then we’re back in the present. Dean and Cindy need a break. They drop off Frankie with Cindy’s father and take off to the liquor store to load up for a night at a theme motel down the road. Cindy’s impatience with Dean is obvious, and Dean’s pretty touchy himself.

Then we’re back in the past. Dean is smitten by Cindy, and contrives a way to meet her again. It’s pretty sweet. And if this was the only story being told, we’d be smitten ourselves. But as we witness the cracks, the decay and the distance of the latter part of this relationship, it becomes increasingly difficult to enjoy the beginning. So achingly bittersweet.

This is what the movie does well, and huge props to the director and his editors, especially, Jim Helton and Ron Patane. The pacing and flash-backing (if that’s a word) allows for a full picture of the highs and lows of the relationship. One informs the other, until in the final act they intertwine flawlessly in a way that delivers a massive emotional punch. And I choose my descriptors carefully here. I felt beaten up and down when the lights came on. The film forced me to think on my relationships, he good moments and bad, and how they dissolved. It’s the antithesis of easy viewing.

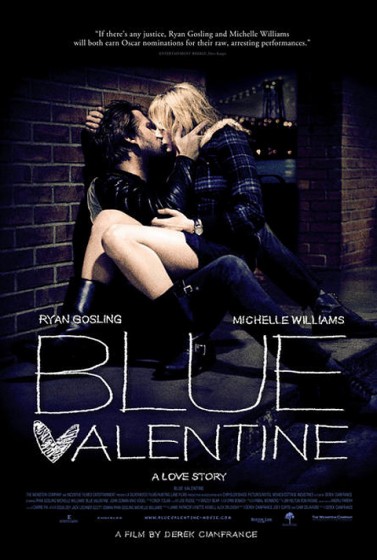

Much of the credit for the picture lies with the performers. Ryan Gosling, who I find to be a gawky Ron Howard-type—his startling appeal to women is one of the great mysteries of life—is excellent here. As Dean, you understand why he’s so beguiled by Cindy, and you understand his frustration later. He hasn’t changed, but she has. And as Cindy, Michelle Williams has less to work with than Gosling, but does more with it. Her character is all in her eyes, in her manner. There was much less of her on the scripted page, so what we’re getting is much more of what the actor brings to the part. She deserves all the attention she’s getting for this role.

My biggest gripe with Blue Valentine is in the overuse of the hand-held camera. The Sundance American indie aesthetic, it rarely works. Here it’s atrocious. You don’t see it used much in foreign films, and if you do, the cinematographers understand that the shots require framing, distance and a certain rhythm. This insistence of the extreme close-up on the performers faces with hand-held makes for claustrophobic viewing, but it doesn’t make any of it seem more gritty or authentic, rather it’s shallow and irritating. The director should have had more trust in his cast and script. There is a beauty to the film, but the scenes that linger in the memory are ones where the camera is set back, giving the moment a chance to breathe. Do we really know what that theme motel room really looked like? No. We know what the performers faces looked like lit in neon blue. It didn’t work at all.

The bottom line: Excellent performances, a wrenching script, set in moving images that regularly ache for a tripod and a dolly.